The rationale for management of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is well established — treatment reduces the risk of macrosomia and its attendant complications. This Journal has carried the views of proponents of lower diagnostic and treatment targets for GDM in the context of updated Australian guidelines.1,2 In this article, we focus on the costly and potentially deleterious effects of suggested lower treatment targets. We argue that such targets are based on insufficient interventional data, create potential health and medicolegal risks and pose great problems for implementation, particularly to providers in regional and remote areas such as our own health district, which services an area about the size of Victoria. In our view, the disadvantages of lower treatment targets currently outweigh the limited evidence of benefits.

Evidence of risks and benefits to patients

Three key trials have informed current practice for managing GDM. The Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study (ACHOIS), an interventional study of 1000 women enrolled over about 10 years to 2003, used lower diagnostic thresholds as well as lower treatment targets.3 Treatment targets were blood sugar level (BSL) of 5.5 mmol/L (fasting) and 7.0 mmol/L (2 h postprandial) in the intervention group. These treatment targets are now the standard of care in many Australian centres. The comparator control group caregivers were unaware of the diagnosis of “glucose intolerance of pregnancy” (the prevailing terminology at the time). Further investigation and management by the treating clinician was permitted if indicated. The ACHOIS trial showed a significant improvement in the intervention group for the primary composite fetal outcome measure (death, shoulder dystocia, bone fracture and nerve palsy) with increased rates of induction of labour in mothers and an increased rate of admission of babies to the neonatal nursery. Interestingly, the trial did not show a statistically significant reduction in caesarean section rates.

A smaller trial in the United States studied the effect of treatment of mild hyperglycaemia among women recruited from 2002 to 2007.4 Using a 3-hour 100 g oral glucose tolerance test, mild GDM was diagnosed if the fasting glucose level was less than 5.3 mmol/L with two or three timed glucose measurements that exceeded established thresholds of 10.0 mmol/L at 1 h, 8.6 mmol/L at 2 h, and/or 7.8 mmol/L at 3 h. Treatment targets of 5.3 mmol/L (fasting) and 6.7 mmol/L (2 h postprandial) were then applied to the intervention group. The trial did not show a difference in the chosen primary perinatal composite outcome (perinatal death, neonatal hypoglycaemia, hyperbilirubinaemia, elevated cord C-peptide level, and birth trauma). The rate of induction of labour was not different for the intervention group; and caesarean section and shoulder dystocia rates were reduced.4

The large observational Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study showed a continuous relationship between fasting, 1-hour and 2-hour glucose levels obtained on a 75 g glucose tolerance test and the risk of increased birthweight, primary caesarean section, elevated cord C-peptide levels, and neonatal hypoglycaemia.5 No obvious threshold where risk overtly increased was found. GDM diagnostic criteria were subsequently revised: it was suggested that a diagnosis of GDM should be made on the basis of blood sugar levels that correlated with a 1.75-fold increased risk of specific fetal measures (birthweight > 90th percentile, percentage body fat > 90th percentile, and cord C-peptide level > 90th percentile).6 The HAPO study did not specifically address any ongoing glycaemic measures throughout pregnancy, and the subsequently suggested diagnostic criteria have not been uniformly adopted, owing to concerns and debate outside the scope of this article.

The continuous relationship between increased glucose measures and increased risk of complications presents both a scientific and philosophical challenge — where a continuous relationship occurs in medicine there is no firm boundary to the disease entity. The definition of disease is one that the profession decides. We argue that in such areas, interventional data are even more important for establishing cut-off points. Harm to our patients must be captured and weighed against the advantages of further intervention. While there is useful information about normal glycaemic values in pregnancy,7 recent articles, including a meta-analysis, have commented that randomised controlled trials (RCTs) showing benefits of intervention in this area were scarce and data quality poor, particularly with regard to postprandial values.8

Thus, based on the current uncertain interventional data regarding milder hyperglycaemia, it would seem difficult to support treatment thresholds being reduced even further to 5.0 mmol/L fasting, 7.4 mmol/L at 1 h and 6.7 mmol/L 2 hours after meals for Australian women.2 These targets (Box 1) are arguably the most aggressive in the world. Indeed, Nankervis and colleagues state that such targets should, ideally, be examined by RCTs.13 We would greatly prefer such interventional studies be conducted and prove overall benefit before adoption of the revised targets.

It is noteworthy and problematic that a fasting BSL less than 5 mmol/L also conflicts with current Diabetes Australia advice that patients on insulin should have a BSL “above 5 to drive”;14 no driving before breakfast may not be practical for some women.

We are concerned that a treatment target of 5.0 mmol/L fasting will expose women to the risk of hypoglycaemia, particularly given that current international standards for blood sugar monitors allow for a 15% error margin (ie, a BSL of 4.0 mmol/L could be 3.4–4.6 mmol/L). Indeed, in a recent study, a fifth of monitors tested failed the looser standard of a 20% error margin, and half of meters would have failed the new 15% standard without improvements.15 In addition, it is noteworthy that neither the observational HAPO study nor the interventional trial of mild GDM reported maternal hypoglycaemia as an outcome and that overtreatment could potentially lead to an increase in small-for-gestational-age babies among women at risk of placental insufficiency.16

Medicolegal risk and clinical judgement in the real world

Guidelines often allude to notions of clinician judgement as the ultimate authority for patient care.2 Such statements are understandable but can be wishful, particularly in relation to GDM. Many women with GDM will not be seen by specialists, who have greater training in a specific area, better access to diagnostic services (such as ultrasound for determining growth rates) and would be more willing to depart from guidelines. It has been estimated that the new diagnostic criteria will lead to a 35% increase in the number of women diagnosed with GDM.17 Most women will thus be predominantly cared for by diabetes educators, midwives, nurses and general practitioners. This is particularly true in regional and remote areas where specialists are scarce. For reasons of workload and workforce, management of GDM is likely to become even more driven by protocols, adding weight to the importance of guidelines being both workable and correct.

While in Australia it is ultimately courts that determine what constitutes negligent conduct, the opinion of medical experts is persuasive,18 and new lower targets are likely to become the default new standard of care. In practice, many health practitioners will struggle to achieve these targets with many of their patients. Given the large number of women who will be diagnosed with GDM, the range of neonatal medical conditions that can be linked with GDM and the great expectations that accompany pregnancy, a number of adverse outcomes could be litigated in the future. A reduction in the degree of legal protection for Australian health practitioners may be an unfortunate unintended consequence of lower treatment targets that depart from international practice (Box 1).

The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) treatment targets are listed as “suggestions” rather than “recommendations”.2 However, it is plausible that health practitioners will refer to the new ADIPS guidelines without appreciating the difference between the two. With the bewildering pace of medical advances in many fields, most health practitioners are dependent on expert guidelines to provide direction in clear terms.

Human resource and economic cost

The human and economic resources required to manage gestational diabetes are considerable. In the Australian setting, such care is resource intensive and often provided by a multidisciplinary approach that may involve GPs, physicians, obstetricians, midwives, nurses, dietitians and diabetic educators. Education and frequent clinical review are the standard of care. The predicted 35% increase in the number of women diagnosed with GDM will lead to a 13% prevalence of the disease17,19 — all women should receive diabetes and dietary education and will require continued review until birth.

Regional centres like our own often serve not just the immediate town but also support remote towns and communities dotted across a vast area. Most women in our centre receive 2 hours of education followed by weekly phone or email contact and regular visits, increasing in frequency until the birth. Women who require treatment with insulin need further intensive education and may have to travel considerable distances to gain this. They usually have more frequent antenatal cardiotocography and ultrasound monitoring, done in a major centre. The baby must be born at a tertiary centre, and labour is usually induced at around 38–39 weeks’ gestation, leading to an earlier delivery date than for women who are “diet controlled”. Neonates are observed in a special care baby unit overnight.

Many of our patients from rural and remote communities must move to live near our hospital in the last month of pregnancy, at considerable cost to themselves and their families. The non-medical cost borne by our hospital system for transport and accommodation alone for the last weeks of pregnancy is at least $6000 per patient.

Cost-effectiveness research has been rather limited. An older Australian study with different diagnostic criteria and treatment targets compared the intervention group to a routine care group who were not made aware of their diagnosis, and thus, the study is of limited applicability to the current clinical context.20 More recent research concluded that the treatment of milder GDM would not be cost-effective if the cost was greater than US$3555 compared to a baseline cost of US$1786 in the different context of the US health system.21

In our region of Australia, a diagnosis of GDM triggers a series of events that shifts care away from peripheral centres to our own tertiary care facility. We doubt this situation is unique, and it creates a number of deleterious social consequences for women in their separation from their full support structures and families. For our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and remote patients, these social and psychological effects should not be taken lightly.

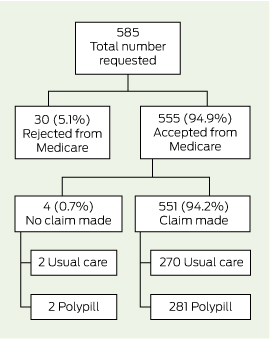

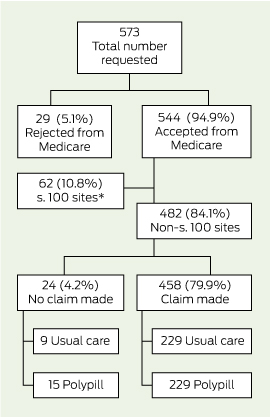

While the effect of new diagnostic criteria has been studied, there is a paucity of data on the effect of new treatment targets. In our centre, the decision to commence pharmacotherapy for GDM is made by endocrinology consultants or advanced trainees. In our prospective audit of 319 patients at our major regional centre over 12 months, we treated women according to our current targets of 5.5 mmol/L (fasting) and 7.0 mmol/L (2 h postprandial), but simultaneously considered what treatment would have been required to treat to targets of 5.0 mmol/L and 6.7 mmol/L. Adopting such a practice would have led to a doubling of patients who needed to start pharmacotherapy by our service (Box 2), with 62% of all women in our clinic requiring pharmacotherapy during pregnancy. Insulin is still the usual first-line treatment in Australia; and studies show that 50% of patients placed on metformin will additionally need insulin to reach targets.22 While it is extremely important that pregnant women are treated optimally, if only 38% of our patients can be managed with diet alone, this will place considerable burden on our already stretched health system. An excessive glucose-centric focus on treating milder GDM may distract from systematically growing contributors to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Obese patients who do not have GDM are contributing to a greater degree to adverse outcomes.23 These factors need to be taken into consideration to avoid misallocation of resources.

Risk of widening the health gap for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians

There is some evidence that exposure to hyperglycaemia in utero is linked to an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus later in life,24 and, consequently, it has been theorised that management of GDM will reduce this risk. It should be noted that there are no such results from interventional data yet, as these studies take many years to complete. A study of the children of women in the ACHOIS intervention group did not show any reduction in their body mass index at 5 years.25

On the other hand, there is considerable evidence that children of low birthweight also have an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes. In this group of babies, including in specific studies of North American indigenous populations, the lower the birthweight the greater the chance of developing type 2 diabetes later in life.26,27 Despite high rates of maternal diabetes, babies of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent have twice the risk of being of low birthweight (< 2.5 kg) compared with the national average (12% v 6%).28 It is unclear whether aiming for a lower birthweight with decreased adipose levels among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is healthier than a more normal birthweight. Given the prevalence of low birthweight babies in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, many of the benefits of GDM treatment, which are largely mediated through reducing macrosomia, may not occur. The high social and economic costs of GDM treatment at lower thresholds certainly will.

The World Health Organization has noted that the lack of ethnically specific data is a limitation of applying knowledge from the HAPO study, and that adaptation may be required for different ethnic groups.29 While the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is numerically small, this group deserves strong consideration given their heavy disease burden and disadvantage. The variation in macrosomia that occurs among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies as a result of GDM may also occur among babies of women from different ethnic backgrounds in our increasingly multicultural country, in which more than a quarter of people were born overseas.30

Conclusion

Although the relationship between maternal blood glucose levels and the risk of macrosomia is a continuous one, there is currently a lack of interventional data to support treatment of GDM to lower targets. To date, studies have not sought to capture the effects of possible maternal hypoglycaemia with lower treatment targets. Some of Australia’s recently revised treatment targets are lower than international practice and impose particular social and economic costs while having limited benefits for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Neither cost-effectiveness nor safety has been established. In our view, an overall analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of lower treatment targets for GDM in Australia suggests that implementation at this stage is premature.

1 Comparison of upper limits of treatment targets for GDM, Australian and international guidelines

|

Guideline

|

Fasting

|

1 h after meals

|

2 h after meals

|

|

|

Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus9

|

5.2 mmol/L

|

7.7 mmol/L

|

6.6 mmol/L

|

|

Canadian Diabetes Association10

|

5.2 mmol/L

|

7.7 mmol/L

|

6.6 mmol/L

|

|

UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence11

|

5.9 mmol/L

|

7.7 mmol/L

|

Not specified

|

|

US Endocrine Society12

|

5.3 mmol/L or 5.0 mmol/L*

|

7.8 mmol/L

|

6.7 mmol/L

|

|

Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society2

|

5.0 mmol/L

|

7.4 mmol/L

|

6.7 mmol/L

|

|

|

GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus. * If this can be achieved without hypoglycaemia.

|

2 Effect of lower treatment targets on a GDM cohort in a major regional centre*

|

Cairns Hospital cohort (n = 319, July 2012 – July 2013)

|

Current practice: 5.5 mmol/L (fasting) and 7.0 mmol/L (2 h postprandial)

|

Proposed practice: 5.0 mmol/L (fasting) and 6.7 mmol/L (2 h postprandial)

|

|

|

Able to be managed with diet and lifestyle control

|

183 (57%)

|

122 (38%)

|

|

Required/would require commencement of pharmacotherapy

|

67 (21%)

|

128 (40%)

|

|

Already on pharmacotherapy when referred

|

69 (22%)

|

69 (22%)

|

|

|

GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus. * Ethics approval was granted by the Cairns and Hinterland Health Service District for gathering of the audit data.

|

more_vert

more_vert