Australia’s Northern Territory has an estimated population of 234 800 people — just 1% of the national total. More than half the population lives in the greater Darwin area or in Alice Springs.1 Of all states and territories, the NT has the highest proportion (30%) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Indigenous Australians), many of whom live in small communities in remote and very remote areas (remoteness area categories 3 and 4).2 Indigenous people continue to experience higher rates of unemployment, lower levels of education and more crowded living conditions compared with other Australians. These social determinants contribute to poor health, including higher rates of chronic diseases and hospitalisation, higher mortality and lower life expectancy.3

Primary care is an effective and efficient means of providing a range of basic health services that improve health outcomes.4,5 However, providing high-quality, cost-effective primary care for a small population dispersed over a large remote area poses challenges. Cost-effectiveness refers to value for money, with better health outcomes achieved at less cost for patients as well as the health system.6 Indigenous people in remote settings experience barriers to accessing health services, including poor availability of general practitioners, geographical isolation, costs associated with travel and variable levels of cultural safety.7,8 Rates of potentially avoidable hospitalisations (PAHs) are indicators of access to primary care and include hospitalisations that may have been avoided by preventing illness or managing chronic disease.8

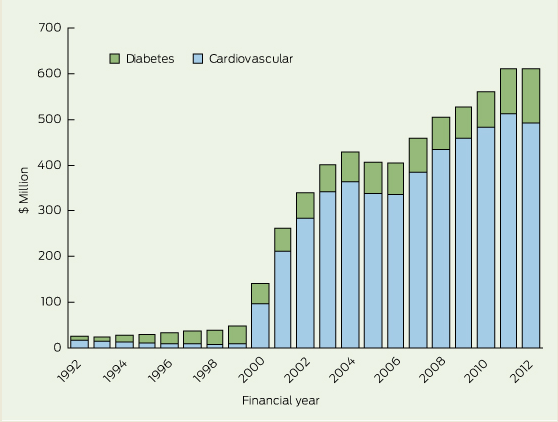

Undiagnosed or poorly controlled diabetes often results in serious complications leading to PAH, disability and premature death. In the NT between 1998–99 and 2005–06, Indigenous people were hospitalised for potentially avoidable causes at four times the rate of non-Indigenous people. This was largely attributable to diabetes complications, and highlights barriers to accessing effective primary care.9 Together with other chronic diseases, diabetes accounts for a large proportion of hospital resources, indirect costs through loss of productivity and impacts on social and family life.10

The NT is disadvantaged with regard to funding, as with fewer GPs in remote areas there is less Medicare and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) subsidisation of consultations and prescribed medicines. Many health services in remote Indigenous communities are provided by nurses and Aboriginal health workers, whose services are largely not covered by Medicare or the PBS.11 This disadvantage is compounded by the high cost of providing primary care in remote locations compared with equivalent services in metropolitan areas.12 Additional funds are provided by the federal government, but between 2003 and 2012, there was a persistent gap of about $37 million annually between actual Medicare payments for NT residents and expected payments based on the national average. The 2012 rate of use of the PBS was only one-quarter of the national average.13 These comparisons are based on a per capita share and do not take into account the greater health needs of the Indigenous population or the cost of delivering services.14

There appears to be a significant need to improve availability of primary care services in remote communities in the NT. While the costs of providing these services are relatively high because of remoteness and a lack of economies of scale, there is a shortage of cost-effectiveness data showing whether there is a net benefit in terms of health outcomes and costs of investing in primary care. We undertook a population-based retrospective cohort study, from a health service perspective, to evaluate the costs and the health outcomes associated with primary care use by Indigenous people with diabetes in remote communities in the NT, using the incremental costs and benefits among a population of patients with different levels of primary care use.

Methods

We linked two databases at the individual level using patients’ unique hospital registration numbers. Individuals were categorised to one of three groups based on their level of use of primary care services. Data were stratified by disease stage. We compared marginal costs and marginal effects on health outcomes using hospitalisations, PAHs, deaths and years of life lost (YLL). We calculated cost-effectiveness ratios with 95% confidence intervals.15 All costs and monetary benefits are reported in 2006–07 Australian dollars.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion was restricted to residents of remote and very remote areas of the NT2 who had been diagnosed with diabetes; were aged 15 years and over as of 1 January 2002; identified as Indigenous; and visited a public hospital in the NT or one of the remote clinics managed by the NT Department of Health at least once during the study period. The quality of Indigenous status reporting in NT hospital admission data is estimated to be 98% accurate.16

All primary care visits and hospitalisations of NT Indigenous patients in the catchment localities of the clinics between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2011 were included for analysis. In the case of multiple residential localities, the locality with the highest frequency of recorded visits or hospitalisations was used. Direct transfers from clinics to hospital were not included in measures of use.

Classifications

Diabetes was defined using the International Classification of Primary Care, 2nd edition (ICPC-2)17 and the Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups, Version 4 (AR-DRG)18 (Box 1). PAHs were identified using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM).19 The principal diagnosis and procedure codes and up to nine secondary codes were used to identify complications of diabetes and PAHs.20

Data sources

We used two administrative databases: the primary care information system (PCIS) and the Caresys hospital admission data system. Data from 54 remote clinics and all five public hospitals in the NT for the 10 years 2002–2011 were extracted for statistical analysis.

We used the government accounting system to extract financial data for primary care costs. Operational and personnel expenditures were allocated based on activity. These expenditures covered patient travel, property maintenance and cleaning, and salaries for doctors, nurses and Aboriginal health workers. Costing information was derived using a “top-down” approach based on the total remote health expenditure and total clinic visits. The mean cost per visit was derived by dividing the total recurrent expenditure by the total number of clinic visits. Hospitalisation costs were taken from the national hospital costing data collection which excluded capital expenditure and patient travel. Indigenous patients in remote communities are not required to contribute a copayment for their care. We did not include any incidental costs borne by patients.

Statistical analysis

The two variables of interest were disease stage and primary care use. To define disease stage, patients were allocated to one of three groups depending on disease severity. ICD-10-AM and ICPC-2 were used to identify new cases and complicated cases. A new case was identified by checking previous health records. A new diagnosis was assumed if the patient did not have a previous diabetes-related hospital admission or clinic visit. The three groups were:

- New cases: patients with a new diagnosis and without complications, as identified by applying the formula in Box 2;

- Established cases: patients who were neither a new nor a complicated case;

- Complicated cases: patients with one or more disease complications in any field of diagnosis, as defined in Box 1.

Patients were also allocated to one of three groups according to annual number of primary care visits:

- Low-use group: 0–1

- Medium-use group: 2–11

- High-use group: ≥ 12.

Recommended best practice in the CARPA (Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association) Standard Treatment Manual 5th edition was used to develop the range of annual visits for each group.21

Propensity score matching and weighting were used to improve the comparability of the three groups.22 The propensity score was computed using key demographics and numbers of chronic diseases. A χ2 test was used to check comparability of the three groups.

Outcomes were measured in terms of annual hospitalisation rates (mean number of hospitalisations per person); annual PAH rates; deaths per 100 population; and YLL per person for between-group comparison. Deaths were identified using both PCIS and Caresys data. Age at death and Australian age-specific life expectancy were used to estimate YLL. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. The cost-effectiveness ratio (CER) was calculated as the incremental cost per hospitalisation averted for both medium- and high-use groups, compared with the low-use alternative. If the CER is less than the “willingness-to-pay” threshold (a criterion for determining cost-effectiveness), that level of use is deemed cost-effective.15 The mean hospitalisation cost in the NT in the 2006–07 financial year was used as the threshold for hospitalisation assessment. The net benefit, expressed in monetary terms, was evaluated on the basis of primary care costing, hospitalisations saved or YLLs averted and the willingness-to-pay threshold. To assess the uncertainty relating to the cost-effectiveness of primary care, we calculated a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve,15 which allows estimation of the probability that primary care is cost-effective in reducing hospital admissions or YLLs, against different values placed on a hospital admission or a year of life. The statistical value of a life-year was $120 000 for the YLL assessment threshold.23 SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc) was used for statistical analysis.

Ethics approval for this project was obtained from the Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 2012-184) and from the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 12-57).

Results

A total of 14 184 patients were eligible to be included in the study. After propensity score matching, there were no significant differences in age (P = 0.980), sex (P = 0.354) or number of comorbidities (P = 0.348) between the low-, medium- and high-use groups. The mean cost per primary care visit in 2007–08 was estimated at $175. The mean cost per hospitalisation was $2915 (AR-DRG hospital inpatient costing is based on 2007–08 and 2008–09 financial year figures).

Overall, compared with the low-use group, the medium- and high-use groups (patients who used primary care two or more times annually) experienced lower rates of annual hospitalisation, PAH and death and fewer YLL (Box 3). Among complicated cases, the medium-use group had a lower mean annual hospitalisation rate than the low-use group (1.2 v 6.7 hospitalisations per person [P < 0.001]); the mean annual PAH rate was lower (0.72 v 3.64 per person [P < 0.001]); and the death rate and YLL were also lower (1.25 v 3.77 per 100 population [P < 0.001] and 0.29 v 1.14 per person-year [P < 0.001], respectively). Only marginal differences were observed for patients using primary care ≥ 12 times annually. For new cases in the medium-use group compared with the low-use group, the death rate was lower (0.48 v 2.17 per 100 population [P = 0.001]), as were YLL (0.13 v 0.81 per person-year [P < 0.001]). Lower rates were also shown for established cases in the medium-use group compared with the low-use group (deaths, 0.15 v 1.65 per 100 population [P < 0.001]; YLL, 0.05 v 0.57 per person-year [P < 0.001]).

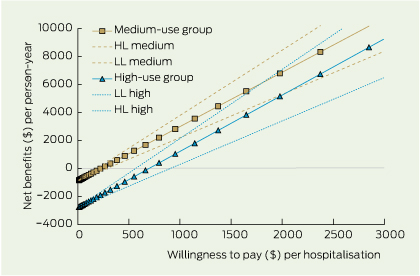

The net health benefits in saved hospitalisations provide a summary measure for the value-for-money of primary care. The net health benefit, as measured by hospitalisations saved per person per year, is achieved at a lower cost when primary care is used between two and 11 times per year. While higher use of primary care achieves slightly greater net benefits, it does so at a greater cost as measured by willingness to pay (Box 4).

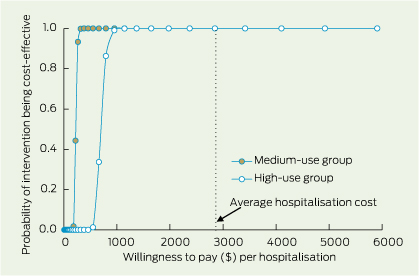

Using 2007–08 and 2008–09 financial year figures, there is an almost 100% probability that both medium and high primary care use are cost-effective in terms of hospitalisations avoided (Box 5).

Investing $1 in medium-level primary care for people with diabetes in remote Indigenous communities could save $12.90 in hospitalisation costs. Investing $1 in high-level primary care use could save $4.20.

The cost of preventing one hospitalisation for diabetes was $248 for those in the medium-use group and $739 for those in the high-use group. In both cases the cost was much less than the mean cost of one hospitalisation, $2915.

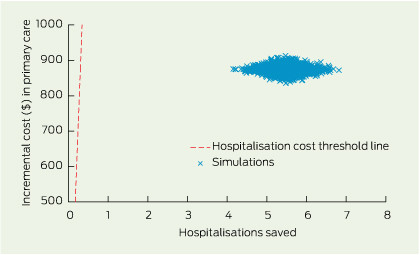

Uncertainty in the cost and effect estimates was assessed by 2000 bootstrapped simulations (Box 6).

Discussion

In the NT, improving the availability of primary care services is the key to improving access.7 The current model of service delivery in the NT results in low rates of primary care use and high rates of hospitalisation, suggesting patients with diabetes are not receiving optimal care aimed at monitoring and preventing complications. Investment in primary care in remote areas in the NT is costly compared with metropolitan settings.12 However, the alternative, hospital-based care, is even more expensive and results in poorer health outcomes. Our study has shown that improving use of primary care would not only yield better health outcomes for patients with diabetes, but would be cost-effective. The savings calculated in this study could be increased by improving the social determinants of health, in which process primary care has an important role through intersectoral action.4

These results are valuable to policymakers and health service planners charged with resource allocation. While there is general agreement in the international literature that improved access to primary health care results in fewer PAHs,24 evidence that this is true for remote communities in Australia and that this is cost-effective is scarce.25 Our study shows that improved access to primary care is both cost-effective and associated with better health outcomes for residents of remote communities. The results may be generalisable for other chronic diseases and to other jurisdictions in Australia. They may also be relevant to other countries where remoteness poses similar challenges.

The results are also of value to primary care managers and service providers who can aim to ensure their patients with diabetes are using services adequately (2–11 times per year). In Indigenous communities, it is particularly important that primary care services are culturally appropriate and reflect community preferences, including connection to culture, family and land, and opportunity for self-determination.26

Our study has limitations. Researchers did not have access to mortality data beyond 2007 and used hospital and PCIS mortality data only, so some deaths may have been missed. We did not have access to data from Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services, and acknowledge that some patients may have been using primary care elsewhere. Some patients undergoing renal dialysis in hospital may have obtained primary care there rather than in their home community. A sensitivity analysis revealed that eliminating renal dialysis hospitalisations made little difference to the outcome (results are not reported). We did not include costs incurred in transporting patients from remote locations to hospital, so the total costs of hospitalisation are an underestimation. We were not able to eliminate any potential confounding effects of distances from patient’s residence to clinics or to hospital due to lack of data on geocoded localities.

Indigenous people in remote communities in the NT experience high rates of diabetes and poor access to primary care with resultant high mortality, morbidity and hospitalisation rates. This study used reliable, linked data to provide new evidence that there are significant cost savings and better health outcomes for patients with diabetes when access to primary care is improved.

1 Disease groups, definitions of diabetes and complications of diabetes

|

Coding

|

Diabetes

|

|

|

Primary care ICPC-2 codes

|

T87, T89, T90

|

|

Hospital AR-DRG codes

|

F11A, F11B, F13Z, K01Z, K60A, K60B

|

|

Hospital ICD-10-AM codes

|

E10-E14

|

|

ICPC-2 complication codes

|

A07, F83, K01, K02, K74-K76, K86, K89, K90, K91, N94, U88

|

|

ICD-10-AM complication codes

|

R40, R07, I20-I25, I10, G45, G46, I60-I69, H35, H36, G54-G64, N00-N19

|

|

|

ICPC-2 = International Classification of Primary Care, 2nd edition. AR-DRG = Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups, version 4. ICD-10-AM = International Classification of Diseases.

|

2 Criteria used for deciding a new case of diabetes

|

Data source

|

Criteria*

|

|

|

Hospital data

|

(last admission > 3 years AND no diabetes) OR

|

| |

(last admission > 2 years AND no diabetes in the last two admissions) OR

|

| |

(last admission > 1 month AND no diabetes in the last three admissions)

|

|

Primary care data

|

(last visit > 1.5 years AND no diabetes) OR

|

| |

(last visit > 1 year AND no diabetes in the last two visits) OR

|

| |

(last visit > 1 month AND no diabetes in the last three visits) OR

|

| |

(last visit ≤ 1 month AND no diabetes in the last four visits)

|

|

|

* A new case must satisfy one of the criteria in both hospital and primary care data.

|

3 Mean annual hospitalisation, potentially avoidable hospitalisation, death rate and years of life lost for Indigenous people with diabetes in remote communities in the Northern Territory, by primary care use group, 2002–2011

| |

Mean annual rate (95% CI)

|

|

No. of patients, and outcomes, by disease stage

|

Low-use group (0–1 primary care annual visits; n = 1421)

|

Medium-use group (2–11 primary care annual visits; n = 1892)

|

High-use group (≥ 12 primary care annual visits; n = 772)

|

|

|

New cases

|

n = 119

|

n = 63

|

n = 18

|

|

Established cases

|

n = 278

|

n = 393

|

n = 50

|

|

Complicated cases

|

n = 1024

|

n = 1436

|

n = 704

|

|

Hospitalisations per person

|

|

|

|

New cases

|

0.7 (0.58–0.89)

|

0.8 (0.59–1.04)

|

0.9 (0.46–1.36)

|

|

Established cases

|

0.4 (0.36–0.52)

|

0.7 (0.60–0.77)

|

0.3 (0.16–0.48)

|

|

Complicated cases

|

6.7 (6.56–6.88)

|

1.2 (1.18–1.30)

|

1.0 (0.94–1.09)

|

|

Total

|

5.0 (4.87–5.11)

|

1.1 (1.06–1.16)

|

1.0 (0.89–1.04)

|

|

Avoidable hospitalisations per person

|

|

|

|

New cases

|

0.31 (0.21–0.42)

|

0.35 (0.20–0.50)

|

0.38 (0.09–0.67)

|

|

Established cases

|

0.20 (0.14–0.25)

|

0.38 (0.32–0.44)

|

0.11 (0.02–0.21)

|

|

Complicated cases

|

3.64 (3.52–3.76)

|

0.72 (0.68–0.77)

|

0.57 (0.51–0.63)

|

|

Total

|

2.69 (2.60–2.78)

|

0.64 (0.60–0.67)

|

0.54 (0.48–0.59)

|

|

Deaths per 100 population

|

|

|

|

New cases

|

2.17 (1.32–3.02)

|

0.48 (0.00–1.03)

|

0.00 (–)

|

|

Established cases

|

1.65 (1.17–2.14)

|

0.15 (0.03–0.28)

|

0.46 (0.00–1.06)

|

|

Complicated cases

|

3.77 (3.39–4.16)

|

1.25 (1.06–1.43)

|

0.84 (0.62–1.06)

|

|

Total

|

3.23 (2.92–3.53)

|

0.99 (0.85–1.14)

|

0.80 (0.59–1.00)

|

|

Years of life lost per person

|

|

|

|

New cases

|

0.81 (0.76–0.86)

|

0.13 (0.10–0.16)

|

0.00 (–)

|

|

Established cases

|

0.57 (0.54–0.60)

|

0.05 (0.04–0.06)

|

0.21 (0.17–0.25)

|

|

Complicated cases

|

1.14 (1.12–1.16)

|

0.29 (0.28–0.30)

|

0.20 (0.19–0.21)

|

|

Total

|

1.00 (0.99–1.02)

|

0.24 (0.23–0.24)

|

0.20 (0.19–0.21)

|

4 Net benefits in hospitalisations avoided with 95% confidence intervals, by willingness-to-pay per hospitalisation

5 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for patients in the medium-level group for use of primary care for diabetes, compared with the high-level group, in terms of hospitalisations avoided

6 Bootstrap simulations with 2000 replications on the cost-effectiveness plane of primary care, for patients in the medium-level of primary care for diabetes

more_vert

more_vert