Teledermatology is an innovative model of health care that has the potential to deliver significant benefits for both patients and medical practitioners. These include increased access to specialist services and reductions in travel times, waiting times and costs for patients, and reduced professional isolation and improved access to professional education for doctors.

“Store-and-forward” is a popular form of teledermatology. It involves capturing a still clinical image that is forwarded to a specialist, who later responds with an opinion on diagnosis and management. Teledermatology at the Princess Alexandra Hospital is a successful example of this model of care.1,2

As dermatology is a visually oriented specialty, using digital images for diagnosis is a natural fit. Numerous studies have already shown the diagnostic accuracy and reliability of store-and-forward teledermatology. More rapid diagnosis and initiation of treatment coupled with improved patient outcomes have also been demonstrated.1,3,4

The growth of store-and-forward services coincides with the increasing use of email, faster Internet speeds, the development of electronic health records and the advent of smartphones. Importantly, smartphones provide an accessible mode of capturing and transmitting patient images.

To date, at least two studies have surveyed the use of clinical photography in two separate Australian tertiary hospitals.5,6 Both showed that the use of personal smart phones for capturing clinical images was widespread. However, both studies also revealed inadequate privacy practices, including inconsistencies in the consent process, inappropriate disclosure of images to third parties and poor security practices when personal devices were used.

Mitigating the risks

In Australia, medical indemnity insurers have identified privacy as an emerging medico-legal risk for the profession.7 Breaches of privacy may result in legal action against and reputational damage for individuals and institutions.8,9 Individuals also risk being the subject of a complaint to the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA), a health complaints entity, or an internal hospital investigation.7

In 2014, the Australian Medical Association (AMA) in conjunction with the Medical Indemnity Industry Association of Australia (MIIAA) released a guide for medical students and doctors for the use of clinical imaging and personal mobile devices.7 Its main recommendations include:

-

ensuring the patient understands the reasons for taking the image, how it will be used, and with whom it will be shared;

-

obtaining informed consent before taking a clinical image;

-

documenting the consent process in the patient record;

-

having controls on mobile devices to prevent unauthorised access; and

-

deleting clinical images from mobile devices after saving them to patients’ health records.7

These recommendations highlight key privacy practices for practitioners. However, the AMA and MIIAA advise that the guide should always be read in conjunction with any relevant legislation, and hospital policies and contracts related to clinical images and the use of personal mobile devices.7

Mitigating the risk of breaches of patients’ privacy by health practitioners begins with an awareness of their privacy obligations under the law, together with the privacy protocols of their employer organisations and professional indemnity insurers. Apart from explaining to the patients why an image is necessary, how it will be used, and who will see it when obtaining consent, the law also requires that health practitioners take reasonable steps to protect patient information (including images) from loss, disclosure, unauthorised access or misuse.8,9 Consider the following case scenario:

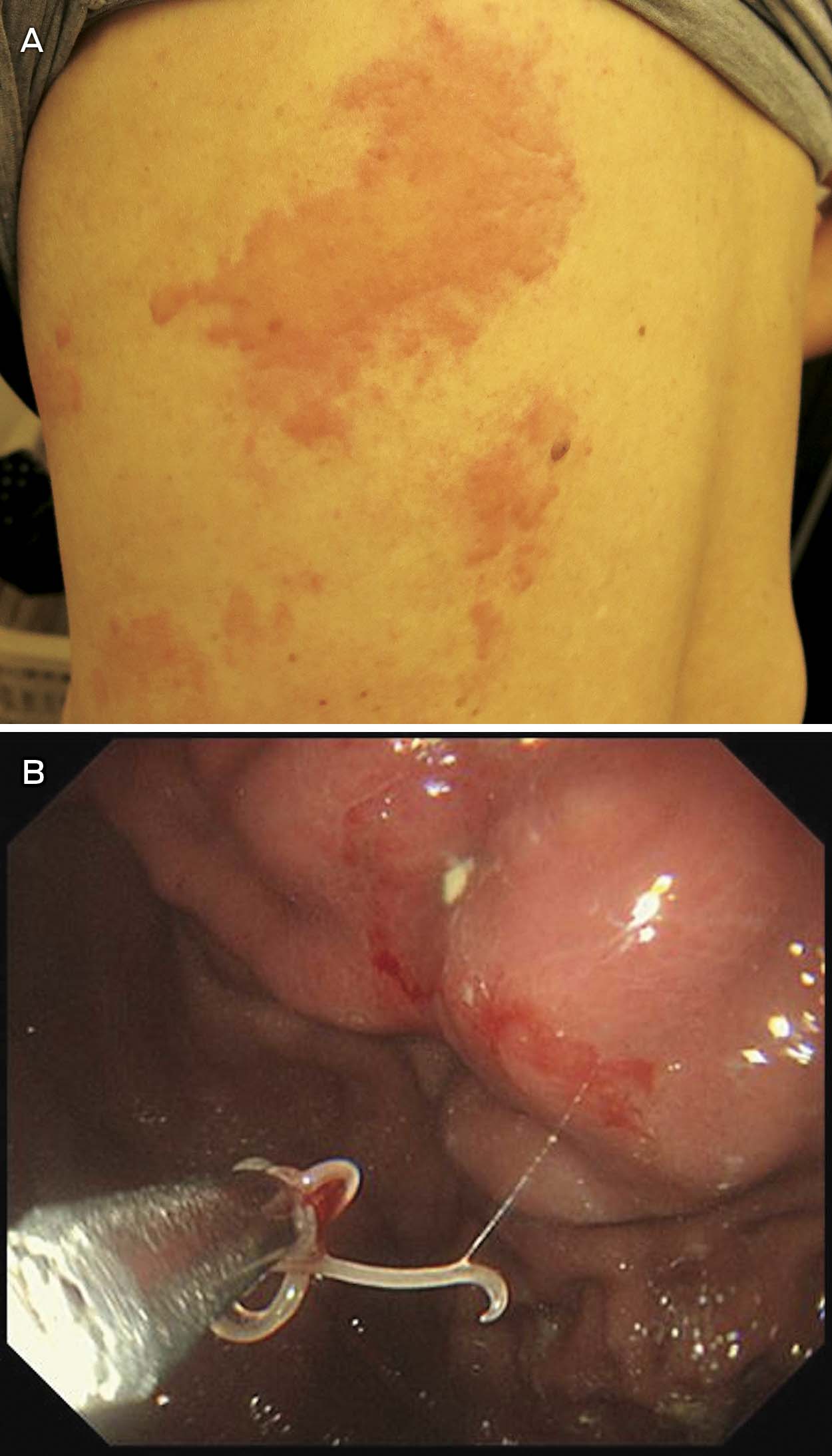

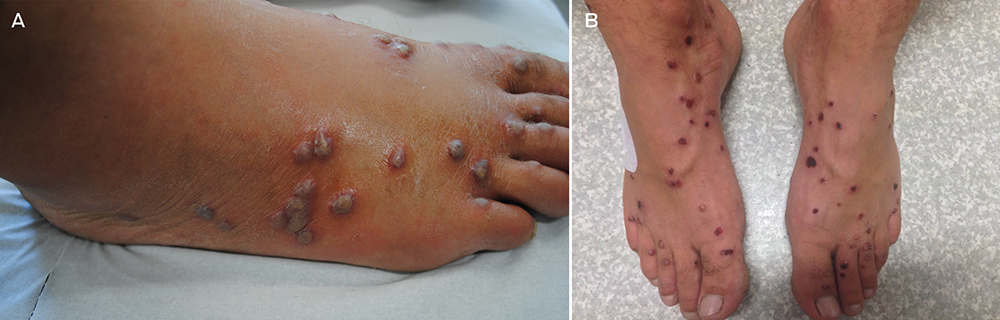

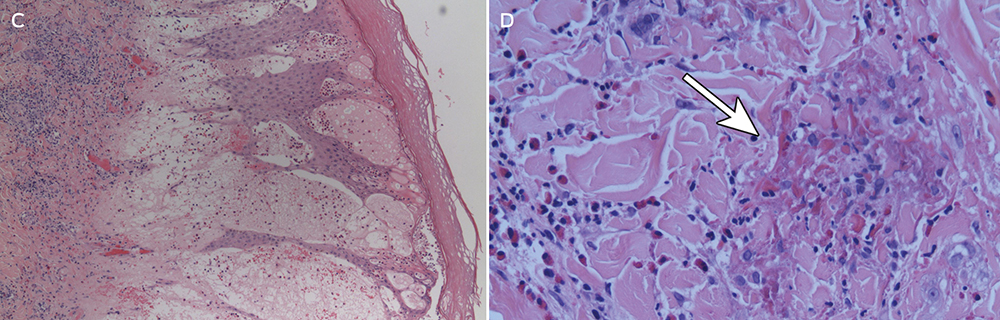

An elderly man presents to the emergency department of a regional base hospital with a new onset rash. The attending resident is not confident to make a diagnosis, but knows of a teledermatology service provided by a tertiary hospital in the nearest capital city. She asks the patient if she can “take some photos of the rash”. The patient agrees. She takes several photos of the patient with her personal smartphone and emails them, from her personal email address, to the on-call dermatology registrar at the tertiary hospital, requesting an opinion. The dermatology registrar reviews the images together with the patient’s history, and replies 2 hours later with a diagnosis of discoid eczema and a recommendation for management. Meanwhile, the dermatology registrar decides to use the patient images for a teaching session for the interns at the tertiary hospital.

Two weeks later the resident’s mobile phone is stolen. The phone had no security features enabled. The thief finds the patient’s images stored on the phone and uploads them to a public website. The thief also peruses the resident’s emails and finds details of the patient, and these are also shared publicly.

In the first instance, the resident should have made it clear to the patient that the purpose of taking the photo was to email the image to a specialist at another hospital to obtain an expert opinion on diagnosis and management. Further, notwithstanding the absence of a direct relationship with the patient, the teledermatology provider does not have consent to use the images for teaching, as the treating doctor did not obtain consent to use the images for this purpose.

Consent may be obtained orally or in writing, although practitioners should follow their institution’s guidelines. When consent is obtained orally, the consent process should be documented in the patient notes. Written consent must still be accompanied by a proper verbal explanation of the procedure.9

After the theft of her mobile phone in this case, the resident would be liable for a breach of privacy and confidentiality. She may also be in breach of the privacy and confidentiality obligations of her employment contract, as well as the conditions of her professional indemnity insurance. As a consequence, the resident could face disciplinary action from her employer or the Medical Board. The hospital may also be vicariously liable for the breach.9 Serious and repeated privacy breaches can attract substantial civil penalties for individuals and organisations under privacy legislation.

Technological precautions

The case above illustrates how easily a simple photograph can result in a costly legal dispute, not to mention untold harm to the patient. This situation could have been avoided if a number of simple precautions had been adopted.

An unlocked phone with patient photographs stored on it is a breach of privacy waiting to happen. Best practice dictates that patient images should be deleted from personal devices as soon as they are added to patients’ health records.7

As best practice may be overlooked during busy periods, security controls on personal smart phone devices, such as passcode locks, should be enabled to prevent unauthorised access. Installing remote locking or data wiping software to personal devices is recommended, as it will allow practitioners to delete data from their devices in the event of theft or loss.

Device settings should be adjusted so that clinical images on devices are not auto-uploaded to social media or back-up sites.7 Once a photo makes its way into the public domain via social media, it is very difficult to limit further sharing of that image.

The process of transmitting a patient image during the teledermatology consultation introduces an additional risk of a breach of privacy. Images should be transmitted via secure methods. Transmitting images through personal email or text messages is not considered secure by some sources, as such methods are typically not encrypted or password protected.10 Despite these concerns, the practice of emailing images is common in many hospitals. Practitioners should be familiar with the policies and systems of their institution or health service in relation to transmitting clinical images.

If a practitioner is required to send images by email or a text message to a colleague or specialist, they should send a test message first to ensure they have the correct email address or phone number for the intended recipient.7,10 Sending patient information or images to incorrect email addresses or phone numbers constitutes an automatic breach of privacy. Once sent, a practitioner has limited control over what the recipient does with that information. Ideally, one should encrypt or password-protect any images before transmitting them, although some may see this extra precaution as an inconvenience.

Like images, email or text messages that were part of the teledermatology consultation should be deleted from personal email accounts and devices after they have been uploaded to the patient record, as these may contain sensitive patient information that is still accessible if a device is lost or stolen. This includes emails saved in the “sent” folder. Automatic forwarding of emails to another email account should be disabled.

Practitioners should also consider the security of other devices that they use for sending emails. Computers and tablets with email management systems that allow email to be accessed on the desktop without logging in are a potential privacy risk. They should avoid sending patient images from an email address that is connected to an email management system. Practitioners should also implement automatic log off on computers and laptops at home and at work that are used to capture and store patient images, and change computer passwords regularly.

Where videoconferencing is being used, the room should be adequately sound-proofed and access should be restricted to those permitted according to the patient’s consent. Any videorecording of the consultation needs to be securely stored.

When consent for using an image for teaching or research purposes is appropriately obtained, best practice dictates that the image should be de-identified where possible, and must comply with relevant research or ethical guidelines.7 Identifying features such as birthmarks, tattoos, metadata, or even the condition itself, if it is rare, should be removed for such purposes.

Practitioner liability

Health care practitioners are personally responsible for patient information they choose to capture and transmit on their personal devices. Practitioners can limit their legal liability in the event of a breach of privacy by demonstrating that reasonable measures were taken to protect patient information. If a privacy breach does occur, clinicians should adopt an open disclosure approach, whereby the breach is notified and acted on. In these circumstances, practitioners should seek advice from hospital management and their medical defence organisations. Once appropriate legal advice has been sought, it may be necessary to inform the patient of the breach, and to explain and apologise.

Conclusions

It remains to be seen how health institutions and policy makers will tackle the issue of patient privacy in the new era of smart phones and teledermatology services. Fear of legal action should not preclude doctors from embracing novel approaches to health care that benefit patients and doctors. Rather, practitioners should take a few sensible precautions to reduce the likelihood of sensitive patient information falling into the hands of malicious third parties.

Before taking that next clinical photograph, individual practitioners should take a moment to review their own privacy practices and make any necessary adjustments. By doing so, practitioners can avoid the financial and emotional cost of a potential lawsuit in the future.

more_vert

more_vert