We thank Ryo Sakamoto and colleagues for their Correspondence regarding our FCET2EC trial on the effectiveness of intensive speech and language therapy in chronic post-stroke aphasia.1 Their point regarding the minimal clinically important difference of the primary outcome measure (Amsterdam-Nijmegen Everyday Language Test [ANELT] A-scale) is of major concern, as already acknowledged in our Article (“To our knowledge, no previously published studies exist on the association of change in ANELT scores with clinical effect.”).

Preference: Anaesthesia and Intensive Care

62

Australia’s hospitals at a glance 2015–16

Australia’s hospitals 2015–16 at a glance provides summary information on Australia’s public and private hospitals. In 2015–16, there were 10.6 million hospitalisations (6.3 million in public hospitals, 4.3 million in private hospitals). The average length of stay was over 5 days (5.7 days in public hospitals; 5.2 days in private hospitals). 1 in 4 hospitalisations involved a surgical procedure. 27% were emergency admissions. 149,000 hospitalisations involved a stay in intensive care. 60% were same-day hospitalisations.

Audit reveals public hospital shifts still dangerous

There are still too many doctors working unsafe shifts in Australian public hospitals, according to an audit of hospital working conditions for doctors.

The AMA’s fourth nationwide survey of doctors’ working hours shows that one in two Australian public hospital doctors (53 per cent) are at significant or high risk of fatigue.

A report of the 2016 AMA Safe Hours Audit was launched on July 15 and showed that while an improvement has been recorded since the first AMA Audit in 2001 (when 78 per cent of those surveyed reported working high risk hours), the result has not changed since the last AMA Safe Hours Audit in 2011.

The report confirms that although there has been an overall decline in at-risk work hours in the past decades, the demands on many doctors continue to be extreme.

“The AMA audit has revealed work practices that contribute to doctor fatigue and stress remain prevalent in Australian public hospitals and can impact on the ability of doctors to work effectively and safely,” said AMA Vice President Dr Tony Bartone.

“It’s no surprise that doctors at higher risk of fatigue reported to work longer hours, longer shifts, have more days on call, less days off and are more likely to skip meal breaks.”

One doctor reported working a 76-hour shift in 2016, almost double the longest shift reported in 2011, and the maximum total hours worked during the survey week was 118 hours, which was no change since 2006.

The most stressed disciplines were Intensive Care Physicians and Surgeons with 75 and 73 per cent respectively reporting they were working hours that placed them at significant or high risk of fatigue.

Research shows that fatigue endangers patient safety and can have a real impact on the health and wellbeing of doctors. This audit shows that the demands on public hospital doctors are still too great and State and Territory governments and hospital administrators need to intensify efforts to ensure better rostering and safer work practices for hospital doctors.

However, the AMA says that reducing fatigue related risks does not necessarily mean doctors have to work fewer hours, just better structured ones.

“It could be a case of smarter rostering practices and improved staffing levels so doctors get a chance to recover after extended periods of work,” Dr Bartone said.

“Safe rostering practices are a critical part of ensuring a safe work environment. Rostering and working hours should contribute to good fatigue-management and a safe work and training environment.

“This includes implementing and supporting rostering schedules and staffing levels that reduce the risk of fatigue, providing appropriate access to rest and leave provisions. And for clinicians, protected teaching and training time, and teaching that’s organised within working hours.

“Employers have an obligation and a duty to provide a safe workplace. They can support staff to maintain a healthy lifestyle and work-life balance by making provisions available for leave and by providing flexible work and training arrangements.

“Research shows that this not only benefits the health and wellbeing of doctors but contributes to higher quality care, patient safety, and health outcomes.

“The Austin and Monash hospitals in Victoria are currently trialling a rostering schedule to mitigate against fatigue based on sleep research. This is the kind of innovative rostering that we’d like to see more of.”

Fatigue has a big effect on doctors in training, who have to manage the competing demands of work, study and exams.

The report showed that six out of ten Registrars are working rosters that place them at significant or higher risk of fatigue compared to the average of five out of ten hospital based doctors.

“Public hospitals need to strike a better balance to provide a quality training environment that recognises the benefits that a safe working environment and teaching and training can bring to quality patient care,” said Dr John Zorbas, Chair of the AMA Council of Doctors in Training.

“The audit suggests that six out of ten Registrars are working shifts and rosters that put them at risk of fatigue. The number of Interns and RMOs working at high risk of fatigue has also increased by 11 per cent compared with the 2011 report.

“Public hospitals in conjunction with medical colleges need to urgently review training and service requirements and implement rostering arrangements and work conditions that create safe work environments and provide for high quality patient care.

“This could include improving access to suitable rest facilities or making sure doctors have access to sufficient breaks when working long shifts.

“The AMA’s National Code of Practice – Hours of Work, Shiftwork and Rostering for Hospital Doctors provides advice on best practice rostering and work arrangements. We’d encourage every hospital to look at this and adopt it as best practice to provide safe, high quality patient care and a safe working environment for all doctors.”

While the profile of doctors working longer hours has decreased across medical disciplines since the AMA’s first survey in 2001, many procedural specialists are still working long hours with fewer breaks.

Three out of four Intensivists (75 per cent) and Surgeons (73 per cent) reported to work rosters that place them at significant and higher risk of fatigue, significantly more than the 53 per cent reported by all doctors.

Further, there is evidence that extreme rostering practices remain with shifts of up to 76 hours and working weeks of 118 hours reported amongst doctors at higher risk of fatigue.

The 2016 Audit confirms that doctors at higher risk of fatigue typically work longer hours, longer shifts, have more days on call, fewer days off and are more likely to skip a meal break.

These are red flags that public hospitals need to urgently address in their rostering arrangements.

The 2016 AMA Safe Hours Audit Report is at: article/2016-ama-safe-hours-audit

The AMA’s National Code of Practice – Hours of Work, Shiftwork and Rostering for Hospital Doctors is at: article/national-code-practice-hours-work-shiftwork-and-rostering-hospital-doctors

CHRIS JOHNSON

Medical role models honoured at AMA National Conference

AMA Woman in Medicine

Dr Genevieve Goulding, an anaesthetist with a strong social conscience and a passion for doctors’ mental health and welfare, has been named the AMA Woman in Medicine for 2017.

Described by her colleagues as a quiet achiever, ANZCA’s fourth successive female President, Dr Goulding has used her term to focus on professionalism, workforce issues, advocacy, and strengthening ANZCA services for Fellows and trainees.

Dr Goulding is a founding member of the Welfare of Anaesthetists Group, which raises awareness of the many personal and professional issues that can affect the physical and emotional wellbeing of anaesthetists throughout their careers.

Dr Michael Gannon, who presented the award at the AMA National Conference, said that Dr Goulding was a role model for all in the medical profession.

“She has raised the profile and practice of safe and quality anaesthesia. She is committed to ensuring patients – no matter their background or position – can rely on and benefit from our health system,” Dr Gannon said.

Dr Goulding continues to effect change with her work on the ANZCA Council and on the Queensland Medical Board, her numerous positions with the Australian Society of Anaesthetists, and her current work with the Anaesthesia Clinical Committee of the MBS Review.

Excellence in Healthcare Award

This year, AMA recognised a true medical leader Dr Denis Lennox, who has made an outstanding contribution to rural and remote health care in Queensland, and to the training of rural doctors.

Dr Lennox has had an extraordinary career since starting as a physician and medical administrator in his home town of Bundaberg in the 1970s.

Dr Gannon said that Dr Lennox had earned this award through his vision and revolutionary training of rural general practitioners and specialist generalists.

“Dr Lennox has been responsible for real workforce and healthcare improvements in all parts of Queensland, particularly through the Queensland Rural Generalist Program which has delivered more than 130 well-prepared Fellows and trainees into rural practice across Queensland since 2005 – an incredible achievement,” Dr Gannon said when presenting the award.

An Adjunct Associate Professor at James Cook University and Executive Director of Rural and Remote Medical Support at Darling Downs Hospital Health Service, Dr Lennox prepares to retire from 40 years of public service.

AMA Women’s Health Award

A nurse and midwife in Darwin, Eleanor Crighton has been awarded the Women’s Health Award – an award that goes to a person or group, not necessarily a doctor or female, who has made a major contribution to women’s health.

Ms Crighton won the award for her outstanding commitment to Indigenous women’s health.

Dr Gannon when presenting the award to Ms Crighton said that she had made a real difference to the lives of Aboriginal women in the greater Darwin region through them gaining access to affordable family planning.

“As an obstetrician, I know the importance of the work of women’s health teams, particularly in Aboriginal community-controlled organisations like Danila Dilba,” Dr Gannon said.

As the Women’s Health Team leader at Danila Dilba Health Service, Ms Crighton has shown her commitment to Indigenous health by pursuing additional studies and gaining personal skills with the aim of filling gaps in health care services.

Ms Crighton has also worked tirelessly to raise awareness of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, and has started training Danila Dilba’s first home-grown trainee midwife, at the same time as pursuing her own Nurse Practitioner studies.

Meredith Horne

[Comment] Beyond resources: denying parental requests for futile treatment

The difficult case of the British boy Charlie Gard1 is the latest in a series of court cases in the UK when parents and doctors have disagreed about medical treatment for a child.2 Charlie Gard is a 9-month-old boy with the rare neurodegenerative disorder severe encephalomyopathic mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome. He is dependent on life support and has been in intensive care at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London, UK, since October, 2016. In such disputes, typically, doctors regard life support treatment as “futile” or “potentially inappropriate”.

[Editorial] Prospects for neonatal intensive care

In today’s Lancet we publish a clinical Series on neonatal intensive care in higher resource settings. The Series, led by Lex Doyle from The Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne, VIC, Australia, includes new approaches to the old nemesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (which still affects up to 50% of infants born before 28 weeks’ gestation), discusses the delicacy of fine-tuning interventions in response to evolving evidence, and explores the frontier of nutritional research by referring to preterm birth as a nutritional emergency.

[Department of Error] Department of Error

Breitenstein C, Grewe T, Flöel A, et al. Intensive speech and language therapy in patients with chronic aphasia after stroke: a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint, controlled trial in a health-care setting. Lancet 2017; 389: 1528–38—In this Article, S Runge should have been listed as part of the FCET2EC study group as a non-author collaborator. This change has been made to the online version as of April 13, 2017, and the printed Article is correct.

[Articles] Intensive speech and language therapy in patients with chronic aphasia after stroke: a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint, controlled trial in a health-care setting

3 weeks of intensive speech and language therapy significantly enhanced verbal communication in people aged 70 years or younger with chronic aphasia after stroke, providing an effective evidence-based treatment approach in this population. Future studies should examine the minimum treatment intensity required for meaningful treatment effects, and determine whether treatment effects cumulate over repeated intervention periods.

Indexation freeze hits veterans’ health care

A recent survey of some AMA members has highlighted the impact of the Government’s ongoing indexation freeze on access to Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) funded specialist services for veterans.

The DVA Repatriation Medical Fee Schedule (RMFS) has been frozen since 2012.

The AMA conducted the survey following anecdotal feedback from GP and other specialist members that veterans were facing increasing barriers to accessing specialist medical care.

Running between March 3 and 10, the survey was sent to AMA specialist members (excluding general practice) across the country.

It attracted interest from most specialties, although surgery, medicine, anaesthesia, psychiatry and ophthalmology dominated the responses.

More than 98 per cent of the 557 participants said they treat or have treated veterans under DVA funded health care arrangements.

For the small number of members who said they did not, inadequate fees under the RMFS was nominated as the primary reason for refusing to accept DVA cards.

When asked, 79 per cent of respondents said they considered veteran patients generally had a higher level of co-morbidity or, for other reasons, required more time, attention and effort than other private patients.

According to the survey results, the indexation freeze is clearly having an impact on access to care for veterans and this will only get worse over time.

Table 1 highlights that only 71.3 per cent of specialists are currently continuing to treat all veterans under the DVA RMFS, with the remainder adopting a range of approaches including closing their books to new DVA funded patients or treating some as fully private or public patients.

If the indexation freeze continues, the survey confirmed that the access to care for veterans with a DVA card will become even more difficult.

Table 2 shows that less than 45 per cent of specialists will continue to treat all veterans under the DVA RMFS while the remainder will reconsider their participation, either dropping out altogether or limiting the services provided to veterans under the RMFS.

In 2006, a similar AMA survey found that 59 per cent of specialists would continue to treat all veteran patients under the RMFS.

There was significant pressure on DVA funded health care at the time, with many examples of veterans being forced interstate to seek treatment or being put on to public hospital waiting lists.

The Government was forced to respond in late 2006 with a $600m funding package to increase fees paid under the RMFS and, while the AMA welcomed the package at the time, it warned that inadequate fee indexation would quickly erode its value and undermine access to care.

In this latest survey, this figure appears likely to fall to 43.8 per cent – underlining the AMA’s earlier warnings. The continuation of the indexation freeze puts a significant question mark over the future viability of the DVA funding arrangements and the continued access to quality specialist care for veterans.

The AMA continues to lobby strongly for the lifting of the indexation freeze across the Medicare Benefits Schedule and the RMFS, with these survey results provided to both DVA and the Health Minister’s offices. The Government promotes the DVA health care arrangements as providing eligible veterans with access to free high quality health care and, if it is to keep this promise to the veterans’ community, the AMA’s latest survey shows that it clearly needs to address this issue with some urgency.

Chris Johnson

Table 1

|

Which of the following statements best describes your response to the Government’s freeze on fees for specialists providing medical services to veterans under the Repatriation Medical Fee Schedule (RMFS): |

|

|

Answer Options |

Response Percent |

|

I am continuing to treat all veterans under the RMFS |

71.3% |

|

I am continuing to treat existing patients under the RMFS, but refuse to accept any more patients under the RMFS |

9.9% |

|

I am treating some veterans under the RMFS and the remainder either as fully private patients or public patients depending on an assessment of their circumstances |

10.8% |

|

I am providing some services to veterans under the RMFS (e.g. consultations) but not others (e.g. procedures) |

5.6% |

|

I no longer treat any veterans under the RMFS |

2.4% |

Table 2

|

Which of the following statements best describes your likely response if the Government continues its freeze on fees for specialists providing medical services to veterans under the RMFS: |

|

|

Answer Options |

Response Percent |

|

I will continue to treat all veterans under the RMFS |

43.8% |

|

I will continue to treat existing patients under the RMFS, but refuse to accept any more patients under the RMFS |

15.5% |

|

I will treat some veterans under the RMFS and the remainder either as fully private patients or public patients depending on an assessment of their circumstances |

21.1% |

|

I will provide some services to veterans under the RMFS (e.g. consultations) but not others (e.g. procedures) |

8.4% |

|

I will no longer treat any veterans under the RMFS |

11.2% |

Hot water immersion v icepacks for treating the pain of Chironex fleckeri stings: a randomised controlled trial

The known Hot water immersion has been shown to be effective for relieving the pain of some jellyfish stings, including blue bottle stings.

The new In the emergency department, hot water immersion was no more effective than icepacks for relieving the pain of major box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) stings.

The implications Protocols recommending icepacks for reducing the pain of major box jellyfish stings should not be changed.

The most appropriate treatment of jellyfish stings is controversial. Although hot water immersion is effective and safe for blue bottle (Physalia spp.) stings,1 the evidence is less clear for other types of jellyfish.2 Hot water immersion has been used to treat some box jellyfish (Cubozoa) stings,3 but icepacks remain the standard approach for treating the pain caused by the major box jellyfish, Chironex fleckeri.4,5

C. fleckeri stings are a problem in northern Australia, and severe stings can result in life-threatening envenoming in children. A more common problem is pain, which in more severe cases can persist for several hours and requires parenteral opioid analgesia.4,6 Current protocols in the Northern Territory recommend that, after vinegar has been applied and life-threatening effects have been treated, pain should initially be relieved by applying ice; if this is ineffective, oral or parenteral analgesia can be provided, depending on the severity of the pain.4,6 The effectiveness of hot water immersion for treating the pain of C. fleckeri stings has not been investigated.

Cubozoan venoms are heat-labile, and C. fleckeri venom is inactivated when briefly exposed to temperatures above 43°C.7 Hot water immersion should therefore be as effective for treating C. fleckeri stings as it is for the stings of other jellyfish.1–3,8 If this were the case, it would allow much more rapid treatment and reduce the need for parenteral analgesia (which increases length of stay in the emergency department). A clinical trial of hot water immersion for blue bottle stings found that the technique was safe; as patients were not exposed to temperatures above 46°C, none suffered burns or other adverse effects.1 However, hot water immersion is unlikely to prevent further envenoming from undischarged nematocysts remaining on the skin after a Chironex sting. Applying vinegar is believed to be effective in inactivating undischarged nematocysts, and is preferred to ice or hot water for this purpose.

The aim of our study was to investigate the effectiveness of hot water immersion in the emergency department for relieving the pain of C. fleckeri stings.

Methods

Study design

We undertook an open label, randomised controlled trial that compared hot water immersion (45°C; active treatment) with the application of icepacks (current standard therapy) for treating the pain of C. fleckeri stings in an emergency department in northern Australia.

Patients

Patients who presented with suspected C. fleckeri stings to Royal Darwin Hospital during September 2005 – October 2008 were eligible for the study. They were included if they had been stung within the past 4 hours and the clinical findings were consistent with a C. fleckeri sting (typical local pain; linear red, raised lesions). Children under 8 years of age were excluded because the primary tool for measuring pain, the visual analogue scale (VAS), is not validated for this age group. Patients with severe envenoming that necessitated resuscitation or antivenom, with a sting clinically consistent with Irukandji syndrome and not with a C. fleckeri sting, with stings to the eyes, or with baseline hypotension (blood pressure below 90 mmHg) were also excluded.

Treatment protocol

Patients were assessed and vinegar applied to all sting sites if this had not already been done. Patients meeting the inclusion criteria were then invited to participate, and their consent (or that of their parents or guardians) obtained. A baseline physical examination was undertaken and patients were asked to score their pain on the VAS. Electrocardiography was performed and an intravenous cannula inserted. Patients were then randomised to receive either hot water immersion or icepacks; treatment was randomised by computer in variably sized blocks of 4 or 6 (eg, AABB, ABAB, or ABABAB, AABBAB), according to which a note marked either with “Hot water immersion” or “Icepacks” was placed into sequentially numbered envelopes.

Patients randomised to receiving icepacks were placed in a normal acute care bed, where icepacks were applied to sting sites for 30 minutes (as long as could be tolerated by patients). Patients randomised to receiving hot water immersion were moved to a bath in the emergency department, filled with water that had passed through a thermostatic mixing valve set to 45°C, and the sting area was immersed for 30 minutes. The patient was supervised in this area at all times. For smaller limb or distal stings, a bucket was used instead of the bath, regularly re-filled to maintain its temperature.

During the treatment phase, VAS scores were collected at 10, 20 and 30 minutes, and blood pressure and heart rate were measured at 30 minutes. After completion of treatment, patients were offered the option to change to the other treatment if pain persisted, or were further observed for 30 minutes. A VAS score was again recorded 60 minutes after the beginning of treatment. If pain persisted after 60 minutes, treatment for a further 30 minutes was offered. Patients were then observed and treated according to the normal box jellyfish sting protocol. On discharge from the emergency department (either home or to an inpatient unit), a final VAS score was recorded, and the time of discharge recorded on the datasheet.

Data collection

Demographic information, details of the sting (site, time, conditions, activity), other clinical effects (radiating pain, systemic effects), standard observations (blood pressure, heart rate), and any treatments (analgesia) and length of stay (LOS) in the emergency department were recorded. The Northern Territory Jellyfish Sting Datasheet4,6 was used for most data collection, and a second datasheet was used for recording VAS and other serial data.

Data analysis

The primary outcome was pain severity (as assessed with the VAS) 30 minutes after commencing treatment. A clinically significant change was defined according to the recommendations of Bird and Dickson:9 for an initial VAS in the range 0–33 mm, the clinically significant change is 16 mm; for 34–67 mm, 33 mm; and for 67–100 mm, 48 mm. Secondary outcomes were the proportion of patients who chose to cross to the alternative treatment; the need for repeat treatment for recurrent or ongoing pain; use of opioid analgesia; LOS in the emergency department; development of regional or radiating pain; frequency with which systemic features of stings developed; proportion of patients with papular urticaria when followed up by telephone 7–10 days after discharge.

Our sample size calculation was based on an earlier study of Physalia stings in which the proportion of patients who were pain-free after hot water immersion increased from 33% to 80%.1 To detect whether hot water achieved the same change (α = 0.05; 80% power), 20 patients were needed for each arm of the trial (40 patients in total). One author (GKI) collected the VAS data, extracted the data, and checked outcomes while blinded to treatment. Data analysis was undertaken after the dataset had been finalised.

Medians, ranges and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated for all continuous variables, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for proportions. The primary outcome was assessed by intention to treat with the Fisher exact test. Secondary outcomes were analysed with the appropriate statistical tests for their data distribution. For all outcomes, P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. All analyses were conducted in Prism 6.03 for Windows (GraphPad Software).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory Department of Health and Community Services and Menzies School of Health Research (reference, 05/42). All patients provided written informed consent for the study.

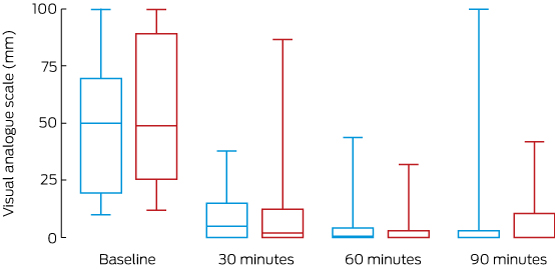

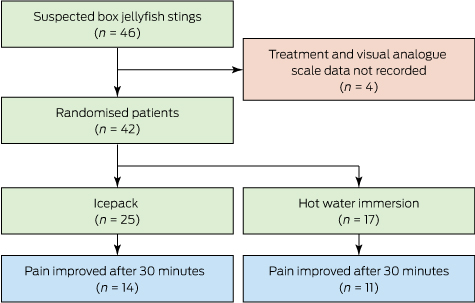

Results

Forty-six patients were recruited, but pain scores and treatment allocation for four people were not recorded. Of the 42 included patients (median age, 19 years; IQR, 13–27 years; 26 were male), 25 were allocated to icepacks and 17 to hot water immersion (Box 1). Twenty patients (48%) had distal limb stings and 14 (33%) developed systemic effects. The demographic, baseline VAS and systemic effects data were similar for the two groups (Box 2). All patients were discharged home from the emergency department, by which time the pain had resolved for 40 of the 42 patients. The median LOS in the emergency department for the 42 patients was 1.8 h (range, 0.5–6.0 h; IQR, 1.1–2.2 h).

Primary outcome

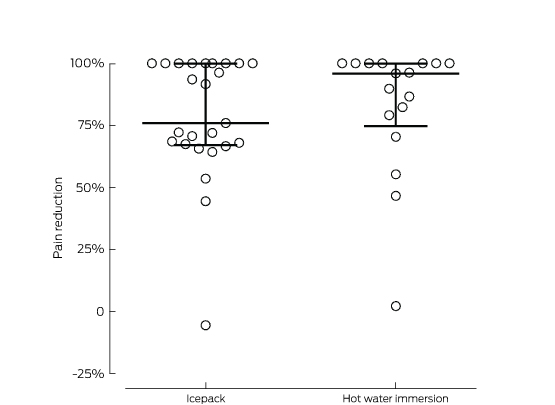

Thirty minutes after treatment commenced, the pain of 14 of 25 of patients (56%) treated with icepacks and of 17 patients (65%) treated with hot water had clinically improved (absolute difference, hot water v icepacks, 9%; 95% CI, –22% to 39%; P = 0.75; Box 3). There was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment arms in the changes in absolute VAS over 90 minutes (Box 4).

Secondary outcomes

One patient in the icepack arm crossed over to hot water immersion; two patients in each arm received intravenous opioid analgesia. The median emergency department LOS for patients treated with icepacks was 1.6 h (IQR, 1.0–1.8 h), for those treated with hot water immersion it was 2.1 h (IQR, 1.6–2.8 h; P = 0.07). No patients re-presented with recurrent pain or developed hypotension. Of seven patients we could follow up, five had developed delayed hypersensitivity rashes.

Discussion

We found that hot water immersion was no better than icepacks for treating the acute pain of C. fleckeri stings. The pain of more than half the patients in each treatment group had decreased after 30 minutes; almost all were discharged from hospital pain-free. There were no severe stings, consistent with severe envenoming being rare.4 Hot water immersion increased the LOS in the emergency department by about 30 minutes, probably because of the practicalities involved in this treatment. There were no differences between groups in the need for opioid analgesia, treatment of recurrent pain, or systemic effects.

The finding that hot water was no more effective than icepacks was unexpected in light of its highly beneficial effect for blue bottle (Physalia) stings.1 Interestingly, the reduction in pain achieved by icepacks in our study (56% at 30 min) was greater than for Physalia stings (33% at 20 min), but the effect of hot water immersion was lower (65% v 87%). There are several potential explanations for the differences, including differing sensitivities of jellyfish venoms to heat. We cannot assume that the effects of treating pain caused by one jellyfish group can be extrapolated to other jellyfish.

Hot water and icepacks were equally effective in our study, possibly because treatment was delayed until the patient reached the emergency department. In the study of Physalia stings,1 hot water immersion was initiated on the beach, often within minutes of the patient being stung, when heat is more likely to be effective. The delay in treatment in our study allowed more time for venom to be absorbed. The effect of heat was therefore more likely to have been symptomatic, rather than providing definitive treatment by inactivating venom. Hot water immersion should be further investigated in a pre-hospital study.

Measurement of pain can be problematic, and a number of tools have been developed. The VAS is one of the most commonly used, including in earlier studies of blue bottle stings1 and red-back spider bites.10 More recent studies have employed a verbal numerical rating score because it is easier to administer (paper is not required)11 and it is used in clinical practice; management of C. fleckeri stings should now include regular assessment of the pain with the verbal numerical score. Correcting for the baseline pain score is controversial, but it enables comparison of patients with differing severity of subjective pain, and this approach has been applied in three previous studies of painful envenoming syndromes.1,10,11 Responses to treatment in our study were similar when relative (Box 3) and absolute VAS (Box 4) data were analysed.

One limitation of our study is that the diagnosis of C. fleckeri envenoming was made clinically; that is, there was no direct evidence that the jellyfish involved in any particular case was C. fleckeri. Previous studies have found, however, that C. fleckeri is the dominant box jellyfish in Darwin Harbour,4,6 with the only other recorded multi-tentacle stings being minor stings by the Darwin carybdeid (four-tentacled box jellyfish), Gerongia rifkinae.12

A further limitation of the study was the small sample size, the result of our anticipating a larger treatment effect for hot water immersion than for icepacks. A larger study would have been required to detect whether hot water immersion had a smaller beneficial effect than icepacks. As investigations of the effectiveness of analgesia usually require large treatment effects (25–50% difference) for the results to be regarded as clinically significant, a larger study may have found a statistically significant difference between the two treatments that was not clinically significant. Another limitation associated with the small sample sizes was the unequal allocation of patients to the two groups because of the block size and exclusions we applied.

Icepacks are simpler, more practical and potentially safer than hot water immersion for the emergency department treatment of box jellyfish stings in tropical Australia. As hot water immersion achieved no major benefit but increased the emergency department LOS, icepacks are more appropriate and remain the recommended emergency department treatment for reducing the pain of major box jellyfish stings after applying vinegar to the wound.

Box 1 –

CONSORT diagram for the study of people with suspected Chironex fleckeri stings presenting to the Royal Darwin Hospital emergency department, September 2005 – October 2008

Box 2 –

Demographic characteristics of the patients allocated to treatment with hot water immersion or icepacks, and the clinical effects associated with treatment

|

|

Icepacks |

Hot water immersion |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of patients |

25 |

17 |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex (males) |

15 (60%) |

11 (65%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Age (years), median (IQR) |

22 (15–30) |

14 (9–23) |

|||||||||||||

|

Sting site: distal limb |

11 (44%) |

9 (53%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Systemic effects |

9 (36%) |

5 (29%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Gastrointestinal (nausea/vomiting) |

5 (20%) |

2 (12%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Respiratory (shortness of breath) |

2 (8%) |

3 (18%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Generalised pain |

2 (8%) |

2 (12%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Baseline visual analogue score, median (IQR) |

50 (20–70) |

49 (26–90) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Proportional change in visual analogue scale (VAS) score after 30 minutes’ treatment with icepacks or hot water immersion*

* The lines mark the medians and interquartile ranges for each treatment group. The difference between the median percentage change in VAS (icepack, 76%; hot water immersion, 96%) was not statistically significant (P = 0.46).

more_vert

more_vert