This letter represents a consensus response study from the Safe Anesthesia For Every Tot (SAFETOTS) initiative which addresses the need for teaching, training, education, supervision, and research inot the safe conduct of paediatric anaesthesia.1

Preference: Anaesthesia and Intensive Care

62

[Correspondence] The GAS trial

The ongoing GAS trial compares cognitive outcomes in infants randomly assigned to receive either awake-regional anaesthesia or sevoflurane-based general anaesthesia during hernia repair. The primary outcome is cognitive performance, measured at 5 years of age. The preliminary report1 described the secondary outcome of cognitive performance at 2 years of age, based on a sample of 532 patients. The average duration of anaesthesia was 54 min. At 2 years of age, equivalent cognitive scores were observed in the two groups.

[Articles] Guillain-Barré Syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study

This is the first study providing evidence for Zika virus infection causing Guillain-Barré syndrome. Because Zika virus is spreading rapidly across the Americas, at risk countries need to prepare for adequate intensive care beds capacity to manage patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Necrotising myositis presenting as multiple limb myalgia

Clinical record

A previously healthy 40-year-old man was referred by his general practitioner to our hospital after a short prodromal period of a sore throat and rapidly deteriorating constitutional symptoms. Most pertinent to his diagnosis was the development of non-traumatic, localised, right calf pain 48 hours before admission that progressed to an inability to bear weight by the time of hospital presentation. On initial physical examination, he had a temperature of 37.8°C, diffuse muscle tenderness in all four limbs and an exquisitely hyperalgesic localised area on the right mid-calf. Examination of his throat showed a diffuse pharyngitis. There was no rash or arthritis, and his cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal systems were all unremarkable at admission.

A blood sample and throat swab were taken and, after an initial blood and microbiological culture work-up, empirical treatment with intravenous flucloxacillin and vancomycin was commenced. Early pathology test results showed a creatine kinase (CK) level of 380 U/L (reference interval [RI], < 171 U/L), serum creatinine level of 158 μmol/L (RI, 55–105 μmol/L), white cell count of 3.1 × 109/L (RI, 4.0–11.0 × 109/L) with increased band forms, and deranged liver function test results, with a bilirubin level of 60 μmol/L (RI, < 20 μmol/L) and alanine transaminase level of 242 U/L (RI, 0–45 U/L).

Over the next 24 hours, the patient’s condition deteriorated, prompting consultation with an infectious diseases specialist. This resulted in a change of antibiotic therapy to ceftriaxone to broaden the coverage of respiratory pathogens, given his acute pharyngitis, and clindamycin to restrict any potential toxin production. By the evening of the second hospital day, the patient was referred to the intensive care unit (ICU) with evolving multiple organ failure. He was now febrile to a temperature of 40°C, with evolving septic shock, pulmonary infiltrates, worsening acute kidney injury (serum creatinine level, 201 μmol/L, and oliguria) and mild delirium. His right calf remained a focal point of concern, with an accompanying tenfold rise in CK level to 3656 U/L.

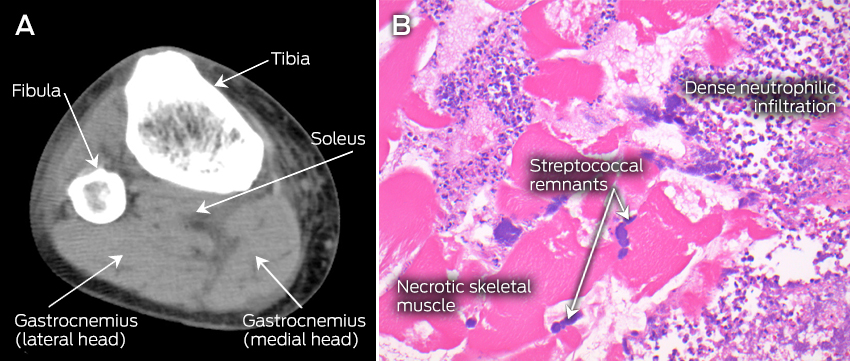

The patient’s condition further deteriorated during his first night in the ICU, necessitating aggressive fluid resuscitation, vasopressor support and haemodialysis. By the morning of the third day in hospital, 12 hours after ICU admission, an isolated, small, tender area of discolouration was noted over the distal posteromedial aspect of the right leg, with no other clinically apparent lesions, but persisting myalgia in all four limbs. This, in conjunction with the confirmation of gram-positive cocci grown from the admission blood and throat swab cultures, prompted the initial consideration of necrotising fasciitis. Subsequent imaging of the lower limbs with ultrasound and non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scans excluded venous thrombosis and fascial thickening, but both tests showed subtle swelling of the calf muscles, suggesting myositis (Figure, A). An urgent plastic surgery consultation mandated surgical exploration of the right calf, and the diagnosis of necrotising myositis (NM) (Figure, B) was subsequently obtained.

Due to the ongoing requirement for frequent soft tissue debridement, the patient was ventilated and transferred to the nearest quaternary hospital. Here, he underwent further imaging of all four limbs and successive debridement of his right leg and both arms for NM on Days 4, 5, 7, 9 and 18 of admission. After receiving confirmation of susceptibility, the ceftriaxone was changed to benzylpenicillin, while clindamycin was retained and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) commenced. Microbiological serotyping confirmed Streptococcus pyogenes with type emm 89.0 strain; exotoxin assays were not conducted. The patient’s total ICU stay lasted 17 days, with liberation from haemodialysis after 7 days and the ventilator after 9 days, resolution of his multiple organ failure, and all four limbs preserved without amputation. After 33 days in hospital, he was discharged to a rehabilitation centre.

Necrotising myositis is a rare but potentially fatal form of infection, predominantly characterised by muscle necrosis capable of rapidly progressing to multiple organ failure in healthy young adults. Published literature attributes group A streptococcus as the most commonly implicated pathogen, but NM has also been associated with groups C and G streptococci, Bacteroides subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus and Peptostreptococcus.1,2

Our case highlights three important clinical lessons. First, NM typically involves a single limb or area. Multiple limb involvement in the initial presentation has only been reported in two previous cases.3,4 Second, despite the widespread limb involvement in our patient, skin discolouration was a subtle, late sign. It presented in only one limb 72 hours after symptom onset, at a stage when the toxic shock syndrome was already apparent. Of 14 previously reported cases, only five describe skin discolouration and two describe local erythema.1,3–8 Third, and most crucially, NM, like necrotising fasciitis, remains a clinical diagnosis, with most investigations being indeterminate.

Increased serum CK level has previously been lauded as a potential early warning sign,4–6 but the initial CK result at our patient’s hospital admission (already more than 48 hours after the onset of symptoms) was only marginally raised (380 U/L). We found two other previously reported cases of NM where the CK level remained below 500 U/L at 48–72 hours after symptom onset.6,7 These findings suggest that excluding NM on the basis of small rises in serum CK level (< 500 U/L) is unreliable. Similarly, a reliance on imaging to provide a diagnosis can result in non-specific or negative findings, delaying a definitive surgical diagnosis and treatment.8 While modern imaging can be performed rapidly, the CT and ultrasound scan findings in our patient were subtle, non-specific and ultimately delayed surgery by 3–4 hours.

Once a diagnosis of NM is suspected, aggressive surgical debridement, appropriate antibiotic therapy and supportive care are mandated for survival. Early surgical intervention has reduced mortality from 100% to 37%,1 but with the consequence of significant long-term morbidity for many survivors. Aggressive group A streptococcal infections respond less well to penicillin and continue to be associated with high mortality and extensive morbidity, leading to the use of adjunctive therapies.9 In a recent observational Australian study of 84 patients with severe invasive group A streptococcal infection, the addition of clindamycin resulted in a significant reduction in mortality, which was further enhanced by the inclusion of IVIG.10 Clindamycin inhibits bacterial protein synthesis at the level of the 50S ribosome, resulting in decreased exotoxin production and increased microbial opsonisation and phagocytosis, while IVIG increases the ability of plasma to neutralise superantigens.9,10 Finally, conclusive evidence is lacking for the use of hyperbaric oxygenation, aimed at reducing hypoxic leucocyte dysfunction, and it was not used for this patient.

Lessons from practice

-

Necrotising myositis is a rare but potentially fatal condition. It is a diagnostic conundrum, often presenting as systemic toxicity and widespread myalgia without focal features.

-

Improved survival is underpinned by early clinical diagnosis, appropriate antibiotic therapy including clindamycin to reduce exotoxin load, and urgent surgical referral. Adjunctive therapies such as intravenous immunoglobulin and hyperbaric oxygenation should be considered based on individual circumstances.

-

Previously suggested diagnostic investigations such as serum creatine kinase levels, ultrasound and computed tomography scans are unreliable, mandating a high index of clinical suspicion to make a diagnosis.

Figure

A: Computed tomography scan (transverse plane) of the right leg, showing subtle hypointense and mildly expanded gastrocnemius and soleus muscles with intact fascia, suggestive of myositis. B: Haematoxylin and eosin stained paraffin section of the right gastrocnemius muscle, showing necrotic skeletal muscle, inflammatory infiltrate with disintegrating neutrophils and colonies of streptococcal bacteria.

Obituary – Professor Tess Cramond

Medical pioneer and former AMA Queensland President Professor Tess Cramond, credited with saving thousands of lives, has died.

Professor Cramond, who helped blaze a trail for women in anaesthetics and medical politics, and whose lifetime of achievement included establishing and heading Royal Brisbane Hospital’s Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic and becoming Dean of the Faculty of Anaesthetists of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, passed away on 26 December, aged 89.

She drew national and international accolades for her work advancing anaesthesia and pain medicine. Among her many awards, she received an Order of the British Empire, she was made an Officer of the Order of Australia, and she was presented with the AMA Women in Medicine Award, the Advance Australia Award and a Red Cross Long Service Award.

Hundreds gathered at Brisbane’s Cathedral of St Stephen on 8 January for her funeral, where many paid tribute to her work as medical adviser to Surf Lifesaving Australia in introducing and promoting the teaching of CPR.

She was also recognised for helping pioneer the advancement of women in medicine.

Born in Maryborough, Queensland, in 1926 as one of four daughters, Professor Cramond entered medical school in the post-war years and graduated in 1955.

She told her friend Dr John Hains in an interview in 2012 that she was drawn to anaesthesia because, “I love the panorama of medicine that anaesthetics provided”.

Professor Cramond was initially reluctant to get involved in medical politics, but eventually agreed to become State Secretary of the Australian Society of Anaesthetists.

Several years later, in 1978, AMA Queensland approached her to become State President – an offer she turned down at the time.

“I had just been appointed Professor of Anaesthetics, and I wanted to get the Anaesthetics Department established properly, so I knocked them back,” Professor Cramond recalled.

But that was not an end to it. AMA Queensland approached her again to become President in 1982.

“When I was asked a second time I thought, ‘If I knock them back again, they will never ask another woman’, so I said yes.”

But Professor Cramond made it clear that one of her proudest achievements was the establishment of the Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic.

The idea for such a clinic came to her during a visit to the United States, where she saw a similar establishment.

When she returned to Brisbane she got to work, and in 1967 the Clinic, which was to become the centrepoint of her career, was established at the Royal Brisbane. She was to serve as its Director for 42 years.

In her 2012 interview, Professor Cramond noted that one of the clinic’s major contributions was to have trained 35 pain specialists since 2000, and was gratified that the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists had established a Faculty of Pain Medicine.

Adrian Rollins

Inappropriate care in medicine

Non-clinicians have based their claims of inappropriate care in hyperbaric medicine on flawed methods

In a recent article in the MJA, Duckett and colleagues presented “a model to measure potentially inappropriate care in Australian hospitals”.1 The article was a summary of their report for the Grattan Institute.2,3 However, with regard to hyperbaric oxygen treatment (HBOT), the summary concealed fundamental flaws in their source data collection and their methods that have resulted in misleading conclusions. Neither Duckett and colleagues nor the accompanying editorial4 cited the two source documents on which the articles were based.2,3 A critical reading of the source documents, cross-referenced with the relevant Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) reports, has identified errors in method and interpretation that invalidate the findings of Duckett et al.2–7

The use of HBOT has been subject to three MSAC reviews since 1998.5–7 As a result of these evidence-based reviews, eight conditions have been accepted for funding by Medicare, including non-neurological soft tissue radiation injury. By exclusion, no other conditions are funded by Medicare. This does not mean there is no supporting evidence for other conditions, as many have not been formally reviewed by MSAC, an important distinction when defining do-not-do treatments.

MSAC reports 1054 and 1054.1 specifically dealt with HBOT for non-diabetic problem wounds and soft tissue radiation injury. MSAC report 1054.1 was inaccurately referenced by Duckett et al, who omitted soft tissue radiation injuries from the title of the report. This omission meant that they included soft tissue radionecrosis in their list of conditions that are inappropriate for HBOT (set out in Box 2 of their article) without alerting the reader to the contradiction.1 The inclusion of soft tissue radiation injury as a do-not-treat condition led to an overestimation in their calculations (soft tissue radiation injury represents 60% of the case load at our hospital), resulting in HBOT accounting for 79% of their total of inappropriate care tally.

By not accurately interpreting their references, Duckett et al allowed errors in data collection to compound into major flaws in their method and conclusions. In the financial year of analysis, 2010–11, there were 15 579 HBOT procedures (Australia-wide) under the relevant Medicare item numbers.8 Of these, 8910 were under item 13015, which represents the combined total for soft tissue radiation injury and non-diabetic problem wounds. Medicare data confirm that both soft tissue radiation injury and non-diabetic problem wounds were funded and appropriate when Duckett’s group collected data and inaccurately defined them as do-not-do treatments. Both the Medicare data and the source data used by Duckett et al recorded the total number of procedures, not the number of patients treated. As each patient received 17.2 HBOTs on average,6 the total number of patients receiving HBOT in Australia in 2010–11 was fewer than 1000 — far less than the number alleged to have received inappropriate treatment.1,2,6 The original Grattan Institute report asserted that “more than 4500 people a year get hyperbaric oxygen therapy when they do not need it”, and “one in four hyperbaric oxygen treatments should not happen”. Both statements are unfounded and incorrect.2

To identify procedures, Duckett et al used the Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI) codes (which have limited clinical relevance and refer only to time for funding purposes), then cross-referenced them against ICD-10 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision) codes, rather than using Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) codes, which are linked to conditions.3 ACHI code 9619100 is not on the MBS; it describes HBOT ≤ 90 minutes, which is not used in Australia by any Medicare-funded facility. Any 9619100 descriptors detected by the study would have demonstrated coding errors. The magnitude of that error cannot be measured owing to lack of detail.

A further source of error was the linking of ACHI codes to ICD-10 codes for comorbidities to discover the clinical condition being treated. HBOT is often implemented as part of multidisciplinary treatment processes in tertiary hospitals. Many patients who receive HBOT have multiple comorbidities. Duckett and colleagues admitted that a limitation of their study was the justified coding errors produced from “a rare combination of patient characteristics”. This comment reflects lack of clinical knowledge — these characteristics are far more common than the authors acknowledge — which has led to underestimation of the magnitude of coding errors.

As an illustration, a retrospective review of all patients receiving HBOT at Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital during the relevant study period shows that 25% of the coding was incorrect. One patient was recorded as receiving HBOT for ≤ 90 minutes for their primary diagnosis of “waiting for residential care” when the treatment was actually for a diabetic ulcer.

The conclusions drawn by Duckett et al are at best misleading.1 It is of great concern that non-clinicians are proposing this analysis to inform health policy and are recommending actions based on flawed methods and misuse of data.

[Articles] Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age after general anaesthesia and awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international multicentre, randomised controlled trial

For this secondary outcome, we found no evidence that just less than 1 h of sevoflurane anaesthesia in infancy increases the risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age compared with awake-regional anaesthesia.

[Comment] Anaesthetics, infants, and neurodevelopment: case closed?

Exposure of young animals, including non-human primates, to all anaesthetic and many sedative agents used in current clinical practice consistently produces neural injury.1,2 Findings of initial studies showed accelerated apoptosis, and later investigations have suggested several other potential mechanisms of injury. This injury is associated with later impairment of learning and memory.3 If these findings are also relevant to children, there might be profound consequences for anaesthetic care.4 However, up to now, all evidence in humans has been provided by observational studies, which have inherent limitations, especially the potential confounding effects of the conditions that necessitate exposure to anaesthesia.

[Comment] EPO in traumatic brain injury: two strikes…but not out?

Despite past failures,1 the promise of clinical neuroprotection in traumatic brain injury continues to drive the assessment of new compounds. The latest of these compounds is erythropoietin, a haemopoietic growth factor from the type 1 cytokine superfamily, which, through several non-haemopoietic mechanisms, has been shown to be neuroprotective in experimental traumatic brain injury.2 In The Lancet, Alistair Nichol and colleagues3 report the results of EPO-TBI, a double-blind, randomised clinical trial of a safety-adaptive dose regimen of erythropoietin (40 000 units subcutaneously once per week for a maximum of three doses) versus placebo, in 606 patients with traumatic brain injury admitted to an intensive care unit, with treatment initiated within 24 h of injury.

[Comment] Myocardial infarction: rapid ruling out in the emergency room

Patients with symptoms of possible acute coronary syndrome make up a large proportion of people who present to emergency departments, where they undergo lengthy, intensive, and costly assessments.1,2 Yet few are finally diagnosed with an acute coronary syndrome. Improvements in methods to exclude acute coronary syndrome are needed to reliably reassure and safely discharge low-risk patients who can then proceed to further investigations as outpatients. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays are reliable and have low thresholds of detection.

more_vert

more_vert