The health status of rural and remote Australian communities is poorer than that of urban communities. Comprehensive primary health care (PHC) services can reduce these health inequities, which by definition are unfair and remediable,1 through the provision of competent clinical care, population health programs, good access to secondary and tertiary care, and client and community advocacy to address health risk factors and social determinants.2

In rural and especially remote areas, there is strong evidence that poor access to PHC remains a critical barrier, particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and this is reflected in the high rate of avoidable hospitalisations.3 However, there is a paucity of rigorous studies showing the nature of the relationship between models of health care in remote areas and health outcomes.4 Given increasingly scarce resources, high costs and workforce shortages in remote areas, understanding how well services are meeting community needs and improving health outcomes is essential.

This study addresses this gap in knowledge by evaluating a health service partnership in the Fitzroy Valley in the remote Kimberley region of north-west Western Australia.5 The Fitzroy Valley covers an area of 30 000 km2, and the population of about 3500 people is dispersed across 44 communities with a stable core population. Services are provided to both Aboriginal (80%) and non-Aboriginal residents. The hospital, main community clinic and Aboriginal community controlled health services are co-located in the town of Fitzroy Crossing. Daily primary care services and occasional specialist services are provided through community health clinics in larger outlying communities and less frequent services to smaller satellite communities.

The aim of the partnership was to reorientate the existing health services from an acute reactive approach to a more comprehensive PHC approach, as recommended in the National Strategies for Improving Indigenous Health and Health Care.6 Before the partnership, care was largely episodic and reactive to patient-initiated presentations. The objective of this article is to examine how changes in the model of service delivery were associated with increased use of primary care and resultant health outcomes for the population.

Methods

In 2011, after the health service reorientation, a WA State Health Research Advisory Council Research Translation Project grant was awarded to the research team to implement a retrospective evaluation to identify the key events leading to change and their impact.

Evaluation framework

A framework for monitoring the impact of changes to PHC services on population outcomes was developed for the Fitzroy Valley to take into account its specific demography and characteristics. Building on a similar framework used for a small rural community in Victoria,7 this framework incorporates the key requirements for high-quality health service performance8 and draws on the links between structure, process and outcomes described by Donabedian.9 The development of this evaluation framework required a targeted literature review and validation workshops with stakeholders and national experts in rural and remote PHC evaluation.

In order to maximise its transferability to other health services, the framework indicators are consistent with the National Health Performance Authority Performance and Accountability Framework10 and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework.11 The program logic approach underpinning our framework is recommended by the National Strategies for Improving Indigenous Health and Health Care.6 A program logic model uses change theory to describe and identify relationships, and enables the impact of service inputs to be associated with predetermined output indicators, providing an indication of progress towards long-term health improvements. Key inputs were identified and primary health care activity and usage measures were monitored to assess the impact of changes on quality-of-care indicators, mortality, morbidity and health behaviours.12 Indicators and their relationship to policy and the logic model are shown in the Appendix.

Data collection and analysis

Health service data for all residents in the Fitzroy Valley (defined by postcode) from 1 July 2006 to 30 June 2012 were collected and analysed from the commencement of the formal partnership and reorientation of the service. Input data were collected from annual reports, financial reports, workforce data, formal agreement documents and meeting minutes of the three partner health service organisations responsible for delivering care into the Fitzroy Valley: the Kimberley Population Health Unit (KPHU), Fitzroy Crossing Hospital (FCH) and Nindilingarri Cultural Health Services (NCHS).

Output data relating to PHC activity and service use were accessed directly from health department databases and PHC program implementation from annual reports. Outcome quality-of-care indicators (such as glycated haemoglobin level, blood pressure and receiving antihypertensives) were generated from the electronic patient medical records. The proportion of those eligible who received the service was calculated against individuals enrolled in the health service.

Data were collected by an externally funded research officer. Indicators were extracted electronically from the health department databases and the electronic medical record used by Fitzroy Valley Health Services (Communicare [Communicare Systems]). Quality-of-care indicators were assessed against the National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander for primary health care.13

Data were compared over time to monitor trends in health service usage, activity, quality of care and population health outcomes. Data were analysed using the non-parametric trend command in Stata version 10 (StataCorp), which performs the non-parametric Mann–Kendall test for trend across ordered groups.14 All trend lines with P < 0.05 showed a significant change in values over 2006–2011.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was provided by the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee and the Western Australian Country Health Service Research Ethics Committee, and was supported by the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum Research Subcommittee.

Inputs and intervention

Several key policy events were identified, which together formed the intervention during this natural experiment. Supportive state and Commonwealth primary health care policy was a key fundamental enabler that provided the funding to strengthen primary health care services.

The formal Fitzroy Valley Health Partnership Agreement memorandum of understanding in 2006 between the government health services (comprising a 12-bed hospital [FCH] and community health services [the KPHU and NCHS]) and the community controlled health service facilitated the integration of primary health care services. The formal partnership agreement negotiated over a 1-year period enabled the three organisations to have a single governance structure for allocating funding, sharing a single electronic medical record and delineating areas of responsibility. Responsibility for health promotion, environmental health and cultural safety belonged to the community controlled NCHS; acute inpatient care, primary care clinic and specialist care to the state district hospital (the FCH); and public health, screening and primary care community clinics and programs to the state-operated KPHU.

The partnership accessed Commonwealth funding for PHC programs through Healthy for Life (an Australian Government program to improve chronic disease, men’s health, and maternal and child health primary care services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples), enabling the implementation of a shared electronic medical record with the capacity to collect evaluation data.

Western Australian state health funding (through the Council of Australian Governments Closing the Gap initiative) for chronic disease in 2010 provided funding for additional primary health care positions which were able to be consolidated through the partnership and provided chronic disease management and care planning.

In 2009, an application for a section 19(2) exemption (Health Insurance Act 1973 [Cwlth]) to allow Medicare billing for primary care patient visits was successful.15 This was a significant driver of increased PHC activity by providing additional resources and incentives to commence adult Indigenous health checks and care plans leading to their integration into primary care clinics. Medicare billings by all providers were reinvested in primary health care under the governance of the partnership.

Another key event was the implementation of alcohol restrictions in the Fitzroy Valley in 2008 driven by local community leadership.16 This decreased the acute care workload on health care staff and appeared to increase patient presentation for non-acute care.17

Results

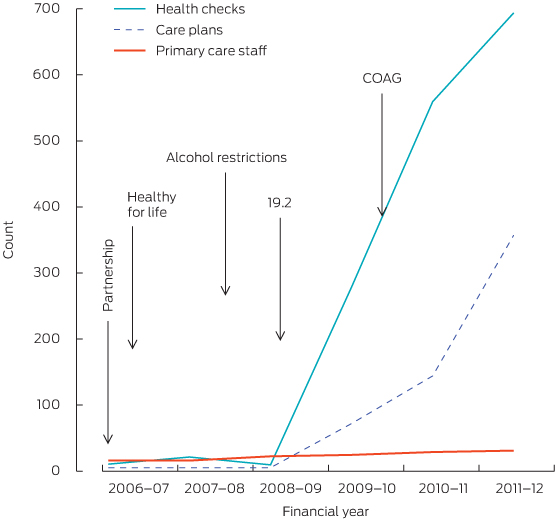

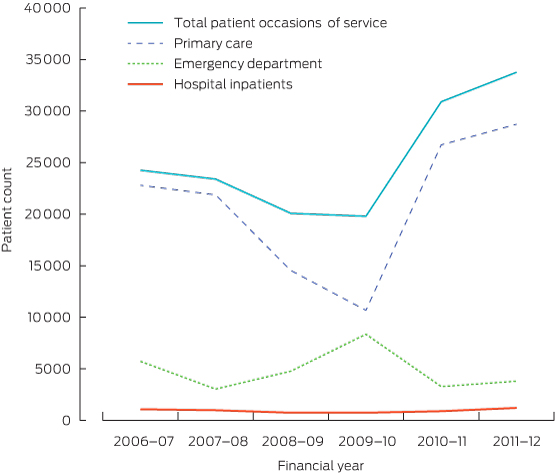

Key policy and structural inputs resulted in an increase in primary care activity (Box 1). There was an overall increase in service activity over the 6-year period, with a relatively constant number of hospitalisations. The increasing trend of emergency department presentations (mostly non-urgent triage category 4 and 5) was reversed, as an increasing number of patients were seen in the PHC clinic (Box 2).

Short-term impact: preventive activity and more equitable access to primary care

Changes in key indicators leading to improved health service performance are summarised in Box 3. There was a significant overall increase in access to PHC services particularly for outlying communities in the Fitzroy Valley. More appropriate service provision led to a large increase in health checks in accordance with national guidelines18 (particularly for males after the commencement of the men’s health program in 2008), and a subsequent increase in the proportion of patients identified with chronic disease or risk factors. Increasing proportional investment in primary health care enabled increased access and appropriateness of services provided.

The NCHS provided regular feedback from the Aboriginal community enabling the health services to provide more culturally appropriate and respectful services. Some of these changes included increased employment of Aboriginal staff and cultural training for all staff, thereby leading to a better understanding of the importance of families and their guardianship roles. In addition, more patient-support people were admitted as boarders, there was increased provision of transport to assist patients to attend appointments and a less structured approach to appointments which enabled patients to attend when it was more convenient. Traditional healers became available on request and smoking of rooms after a death was introduced. These responses to community feedback resulting in more patient centred care were reflected in an increased attendance at follow-up appointments.

Medium-term impact: quality of care

Identifying patients with chronic disease or its risk factors and placing them on care plans with regular interdisciplinary follow-up was prioritised, and resulted in 73% of patients with diabetes having care plans. This systematic approach targeting patients with chronic disease led to an increase in primary health episodes from two to 10 per person per year and a higher proportion of the community attending health services regularly for follow-up and in response to recalls. Despite increasing numbers of patients receiving regular care and completing annual cycles of care for diabetes, there was no statistically significant improvement in glycated haemoglobin levels (< 7%) or in blood pressure levels reaching target values (≤ 130/80 mmHg). (A more detailed study of diabetes management showed improvements in cholesterol levels.)19

Long-term outcomes

There was a decrease in numbers of deaths over the study period, and a decreasing trend in the proportion of hospital admissions requiring emergency evacuation.

There was an increase in screening for alcohol and tobacco use over the 6 years, and a significant increase in the numbers of patients who were ex-smokers, intending to quit and drinking within safe limits (Box 4).

Discussion

Positive changes in health service usage and clinical outcomes were demonstrable despite a number of limitations. Using routine health service data retrospectively reflects the accuracy of individual input and limits data collection to indicators routinely available. The transition from paper-based data recording to dual recording using the electronic patient record between 2006 and 2009 may have contributed to some of the variation in trends before 2009, when the electronic records became largely complete. This may account for small changes in trend in some indicators but not the large increases in key indicators such as increased primary care occasions of service, health assessments and care planning.

These limitations notwithstanding, the partnership between community controlled and government organisations drove a change in philosophy from a reactive acute care system to a more proactive, comprehensive PHC approach. This provided two key elements: population health programs targeting prevention and early intervention for high-risk groups and community advocacy around health risk factors at a population level.

Structural changes led to improvements in performance when compared with mean national key performance indicator data for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.13 These intermediate outcomes are expected to result in further improvements in health outcomes over time.2 This is important given that two-thirds of the gap in health outcomes is estimated to be due to chronic disease.11 Extant literature shows that, after accounting for burden of illness, remoteness and the increased costs of infrastructure, two to seven times the average per capita funding is required by remote Indigenous populations to maximise effectiveness and equity.20 Our study demonstrates that increased primary care investment where capacity to benefit is high can result in measurable positive outcomes in a relatively short period of time.

While improvements in health outcomes are the ultimate goal, intermediate outcome indicators are the most useful for assessing the contributions of PHC because they are sensitive to PHC interventions, and the long lead time from implementation may preclude direct improvements to health outcomes in the short term.2 However, there was an improvement in mortality in the region. Mortality figures for the Derby–Fitzroy Valley statistical local area are decreasing in contrast to other similar regions.21 While we need to be cautious in interpretation because of the small numbers involved, there was a significant drop in the mortality rate over this period. This decrease may have been due to the effects of the alcohol restrictions and was supported by anecdotal evidence from community leaders: “We don’t go to funerals every month like we used to”.

Despite the poor socioeconomic circumstances of the population, improvements in health behaviours can be credited to the health promotion activities of the NCHS, which implemented a comprehensive health promotion program across the Fitzroy Valley, including a quit smoking program. Not only has health education at the individual and community level been a feature of the service, but the alcohol restrictions brought about by strong community action addressing upstream determinants of health were also significant.16,22

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander PHC sector is leading the way with innovative, integrated PHC delivery models under community governance and research linking health service delivery to intermediate health outcomes.23 Our case study builds on the legacy of outstanding leadership and culture of quality improvement across the Kimberley region.24

This study demonstrates changes that are possible with a comprehensive PHC model focusing on the upstream determinants of health, prevention and improved clinical care to meet community needs, even in a challenging remote context. Strong community leadership can maximise the opportunities provided by policy changes and increases in funding, translating them into improvements in practice and health service delivery. These factors are essential enablers and need to be dealt with concurrently for service sustainability requirements to be met.25 Attending to only one or two of these factors is likely to be ineffective, and it was the systematic approach to all of them simultaneously and comprehensively that enabled sustainable change to occur.

Our study is an example of the potency of research embedded in service delivery26 and demonstrates the importance of monitoring the impact of service delivery on the health outcomes of the population. Linking structure to process and outcomes through key indicators can be used as a planning, monitoring and evaluation tool to measure the impact of national and local policies. Resultant evidence can be used to inform policy direction and translate into service delivery changes consistent with the goals underpinning current national health care reform and Closing the Gap policies.

1 Key inputs strengthening primary health care, and their impact on service outputs, Fitzroy Valley, 2006–07 to 2011–12

2 Trends in health service use, Fitzroy Valley, 2006–07 to 2011–12

3 Fitzroy Valley Health Service performance indicators, 2006–07 to 2011–12: trends in primary health care activity

|

Sentinel indicator

|

2006–07

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

P

|

Mann–Kendall

|

|

|

Individuals on electronic health record

|

2160

|

3147

|

3573

|

4176

|

5626

|

5410

|

|

|

|

Occasions of service*

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Town

|

4150

|

8666

|

13 433

|

19 628

|

27 087

|

35 940

|

0.03

|

< 0.01

|

|

Hubs

|

499

|

1925

|

5665

|

8788

|

10257

|

10 147

|

0.04

|

0.02

|

|

Satellites

|

364

|

182

|

476

|

693

|

1205

|

1191

|

0.05

|

0.06

|

|

Total

|

5013

|

10 773

|

19 574

|

29 109

|

38 549

|

47 278

|

|

|

|

No. of health assessments

|

340

|

475

|

525

|

1080

|

1617

|

1789

|

0.03

|

< 0.01

|

|

No. of male health checks performed

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

159

|

268

|

322

|

0.03

|

< 0.01

|

|

Immunisation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Children aged 24–36 months, coverage

|

92%

|

94%

|

95%

|

95%

|

96%

|

96%

|

0.04

|

0.02

|

|

No. of adults immunised against influenza

|

107

|

908

|

1397

|

996

|

1310

|

1405

|

0.07

|

0.06

|

|

No. of Aboriginal patients aged > 15 years screened for biomedical risk factors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Body mass index

|

143

|

199

|

277

|

519

|

760

|

881

|

0.03

|

< 0.01

|

|

Alcohol consumption

|

139

|

142

|

49

|

352

|

262

|

489

|

0.09

|

0.14

|

|

Smoking

|

184

|

151

|

82

|

468

|

727

|

845

|

0.09

|

0.14

|

|

Mean primary care episodes per individual per year

|

2

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

8

|

10

|

0.03

|

<0.01

|

|

Primary care investment: proportion of total funding

|

23%

|

20%

|

25%

|

25%

|

39%

|

34%

|

0.06

|

0.09

|

|

Resident population estimate

|

2664

|

2718

|

2773

|

2828

|

2885

|

2942

|

|

|

|

|

* Primary health care occasions of service: Fitzroy Crossing town, daily; hubs (Noonkanbah, Bayulu, Wangkatjungka) — community health clinics, Mon–Thu; satellites — community health clinics, 2–4 weekly.

|

4 Trends in service quality-of-care outcomes, 2006–07 to 2011–12*

|

Sentinel indicator

|

2006–07

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

P

|

Mann–Kendall

|

|

|

All-cause mortality, crude death rates per 1000 population (95% CI)

|

9.38

(5.71 –13.06)

|

4.78

(2.18–7.38)

|

9.01

(5.48–12.80)

|

3.89

(1.59–6.19)

|

3.12

(1.08–5.16)

|

2.72

(0.83–4.60)

|

0.04

|

0.02

|

|

Diabetes

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No. of patients

|

310

|

337

|

347

|

347

|

380

|

419

|

0.06

|

0.07

|

|

Care plans

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

18%

|

7%

|

78%

|

0.04

|

0.03

|

|

Team care arrangements

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

5%

|

13%

|

73%

|

0.04

|

0.03

|

|

No. of annual cycles of care completed

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

9

|

27

|

34

|

0.09

|

0.14

|

|

ACE inhibitor or ABR

|

43%

|

56%

|

57%

|

79%

|

82%

|

87%

|

0.03

|

< 0.01

|

|

HbA1c level measured in previous 6 months

|

51%

|

53%

|

45%

|

69%

|

72%

|

71%

|

0.09

|

0.14

|

|

HbA1c level ≤ 7%†

|

25%

|

27%

|

20%

|

25%

|

20%

|

26%

|

0.8

|

1.00

|

|

HbA1c level < 8%

|

39%

|

19%

|

39%

|

48%

|

41%

|

43%

|

|

|

|

HbA1c level > 10%

|

31%

|

35%

|

34%

|

31%

|

37%

|

34%

|

|

|

|

BP ≤ 130/80 mmHg†

|

44%

|

34%

|

34%

|

42%

|

42%

|

39%

|

0.9

|

1.00

|

|

Health behaviour

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No. of attendees

|

1290

|

1568

|

2015

|

2164

|

2327

|

2504

|

|

|

|

Regular attendees, > 3 visits over 2 years

|

49%

|

68%

|

77%

|

78%

|

82%

|

79%

|

0.04

|

0.02

|

|

Smoking

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No. of patients screened‡

|

184

|

151

|

82

|

468

|

727

|

845

|

|

|

|

Ex-smoker

|

2%

|

5%

|

10%

|

11%

|

12%

|

13%

|

0.03

|

< 0.01

|

|

Intention to quit

|

10%

|

24%

|

24%

|

26%

|

32%

|

34%

|

0.03

|

0.01

|

|

Alcohol consumption

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No. of patients screened‡

|

139

|

142

|

49

|

352

|

262

|

489

|

|

|

|

Within safe limit

|

11%

|

9%

|

29%

|

21%

|

26%

|

28%

|

0.2

|

0.27

|

|

|

ABR = angiotensin-receptor blocker. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme. BP = blood pressure. HbA1c = glycated haemoglobin. * Data are proportion of patients unless otherwise indicated. † Reference interval. ‡ Aboriginal patients aged > 15 years.

|

more_vert

more_vert