There is international interest in the best methods for improving quality of care in primary health care settings.1,2 As a result, governments and health care organisations carry out large-scale programs, including national quality strategies and accreditation, in an effort to improve the quality of services, enhance patient experience and health outcomes and reduce the cost of care.3–6 Quality improvement (QI) involves “a structured process that includes assessment, refinement, evaluation and adoption of processes by an organization and its providers to achieve measurable improvements in outcomes to meet or exceed expectations”.7

In Australia, a system-wide approach for QI has been driven by the endorsement of national frameworks and policies, including the Quality Framework for Australian General Practice (2007),8 the Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Health Care (2010),9 the National Primary Health Care Strategic Framework (2013)10 and, most recently, the Primary Health Network Quality Partnership Framework (2015).11 Most QI activity in general practice has been motivated by the accreditation process based on the national standards of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP)5 and the opportunity to participate in externally facilitated programs, such as the Australian Primary Care Collaboratives.6 These programs have addressed issues such as chronic disease management, access and e-health and, while these efforts have had a positive impact on improving health care and building practice capacity in these areas, only 2116 out of about 7035 practices have been involved in some aspect.12,13

While the external drivers such as frameworks and accreditation for QI are important, internal factors such as organisational infrastructure, strong team leadership and a culture of QI enable practices to improve their performance and the outcomes of their patients.7,14 However, specific areas that practices choose to deal with through ongoing QI efforts, and the methods they use to do so, are likely to vary based on each practice’s concerns, circumstances, capacity and resources.3 Evidence suggests general practice teams need to “own” the quality agenda, take leadership and be actively engaged as partners in QI.4 QI that is internally led at a practice level, with support from regional networks, is likely to be more effective.15

There are numerous QI tools and resources available for clinical practices and practitioners, with various applications for improving different aspects of quality.16–20 However, the accessibility, utility and quality of these resources are variable.1 There is also increasing evidence suggesting that QI initiatives that take on a whole-of-practice approach, such as the Primary Care Practice Improvement Tool (PC-PIT), Six Sigma and the Clinical Microsystem Assessment Tool, are more effective as they engage all practice staff to improve varying aspects of organisational and clinical practice, while recognising practice context and capacity.21

There has been limited exploration of general practitioners’ and practice managers’ perceptions of, and preferences for, QI tools. Available evidence focuses predominantly on GPs and suggests that the length, format, accessibility, content, relevance, reliability (scientific evidence), skills required for use, perceived ease of implementation and perceived benefits and support are factors that affect their choice of tools and resources for use in practice.22–25

This work follows on from the pilot study and trial of the PC-PIT approach to improve organisation performance in primary care.21,26 The PC-PIT includes seven key elements integral to high-quality practice performance: patient-centred and community-focused care; leadership; governance; communication; change management; a culture of performance; and information and information technology.21,26 During the trial, practice managers identified the need for additional resources to support the PC-PIT and provide a “one-stop shop” for organisational performance improvement.

After conducting a systematic literature review to identify online QI tools and resources to support organisational improvement related to the seven elements in the PC-PIT,27 we conducted this Delphi study to assess their relevance and utility and select a final suite of tools and resources to both complement the PC-PIT and support QI activities in Australian general practice.26

Methods

This study was conducted from November 2014 to August 2015. Ethics approval was granted by the University of Queensland Behavioural and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee (approval number 201000924).

An Expert Advisory Panel evaluated the 53 tools and resources identified in the systematic review (Appendix 1)27 using a modified Delphi technique.28,29 In contrast to the “pure” Delphi process, which provides collated feedback from reviewers back to all reviewers over a series of rounds, in this study de-identified collated feedback was provided to all reviewers during the final (third) round only. This modification was necessitated by the workload and time constraints of the panel members. The modified Delphi process was chosen for its efficient use of time and resources, as well as its ability to minimise the impact of group interaction and influence.30,31 It is also a method for providing valuable expert information where knowledge is incomplete.30

Evaluation process

A five-step approach was used in the evaluation (Box 1).

Step 1. Establish Expert Advisory Panel

A panel of six GPs and six practice managers (as end users of QI tools and resources) who each had more than 5 years’ experience in QI activities in general practice was purposively recruited from practices that had participated in the PC-PIT pilot study in 2013. Of the panel of 12, five were male and seven female, and their practice settings were evenly divided between metropolitan and regional areas. The main task of the panel was to assess, using a standard assessment form, the relevance and utility of selected tools identified through the international literature review.27

Step 2. Develop and pilot assessment form

The pre-tested assessment form (Appendix 2) was based on five domains commonly used for assessing quality of interventions, health information and websites: (i) target audience; (ii) relevance to the PC-PIT; (iii) usability; (iv) strengths; and (v) limitations (pertaining to utility).32–34 A mix of tick-box categories and open-ended questions and statements (eg, “Please comment on the strengths, limitations and your overall perception of the utility of using this tool in your practice”) elicited qualitative feedback from the reviewers. The final section of the form asked reviewers to make an overall recommendation (“I do not endorse this tool”, “I am unsure about recommending this tool” or “I recommend this tool to be used to complement the PC-PIT”) and provide a written justification for the chosen recommendation. A score from 0 to 10 for each tool (where 0 indicated poor utility and 10, high utility) provided additional information about tool recommendations.

Step 3. Data collection

In Rounds 1 and 2, the review process was undertaken using the standard assessment form and scoring system (Appendix 2).

Round 1 review: QI tools and resources were randomly divided into six groups of about nine tools each. Two reviewers (a GP and a practice manager) were allocated a group of tools to review. The reviewers categorised the tools and resources as recommended, not recommended or unsure, and provided reasons for their decision.

Round 2 review: Tools and resources that had received an unsure recommendation from both reviewers, or divergent recommendations (ie, one reviewer had recommended the tool, but the second reviewer did not recommend it or was unsure), in Round 1 were sent out for Round 2 review by different pairs of reviewers using the same assessment form.

Final review: The final review included the tools and resources previously recommended by both the practice manager and GP in Rounds 1 and 2, plus the three highest scoring (those that scored 29/40) divergent Round 2 tools and resources that were relevant to the Australian context, as indicated in the reviewer justification comments. All 12 members of the Expert Advisory Panel were invited to participate in the final review, and nine (five practice managers and four GPs) were able to do so. Each was sent a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) that included online links to the tools and resources, with de-identified comments and scores from the Round 1 and 2 reviews. Using the modified Delphi technique, reviewers were instructed to consider the comments and scores from their peers and make a decision to accept or reject each tool or resource for inclusion in the final suite, along with providing a brief reason for their decision. This process provided reviewers with a final opportunity to revise their judgements in light of the collated information from previous rounds.

Step 4. Data analysis

Quantitative data were entered into a spreadsheet and imported into SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS). Data were analysed using SPSS and Microsoft Excel 2013. One of the research team (L C) completed an additional accuracy check of about 10% of coded and entered data. Quantitative results are reported using descriptive statistics. We explored free-text responses using NVivo 10 (QSR International) and used thematic analysis to identify common themes relating to the strengths and limitations of each of the tools and resources.

Step 5. Select suite of recommended tools to support PC-PIT

Tools and resources were selected for inclusion in the final suite if they received five or more recommendations from the expert panel of nine in the final review round.

Results

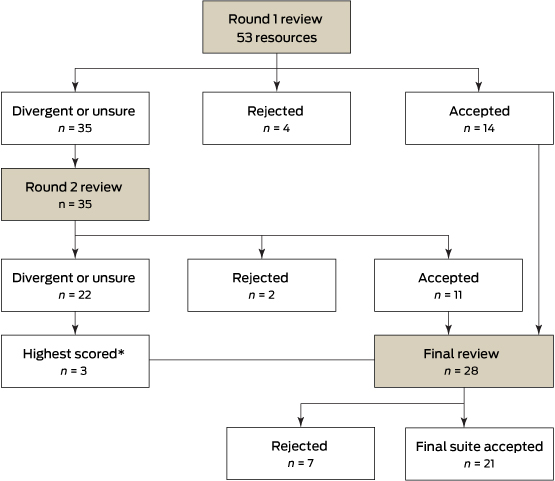

Of the original 53 tools and resources provided to the Expert Advisory Panel, 28 were included in the final review round. Of these, 21 were selected for inclusion in the final suite. Box 2 shows the number of tools and resources accepted or rejected in each round.

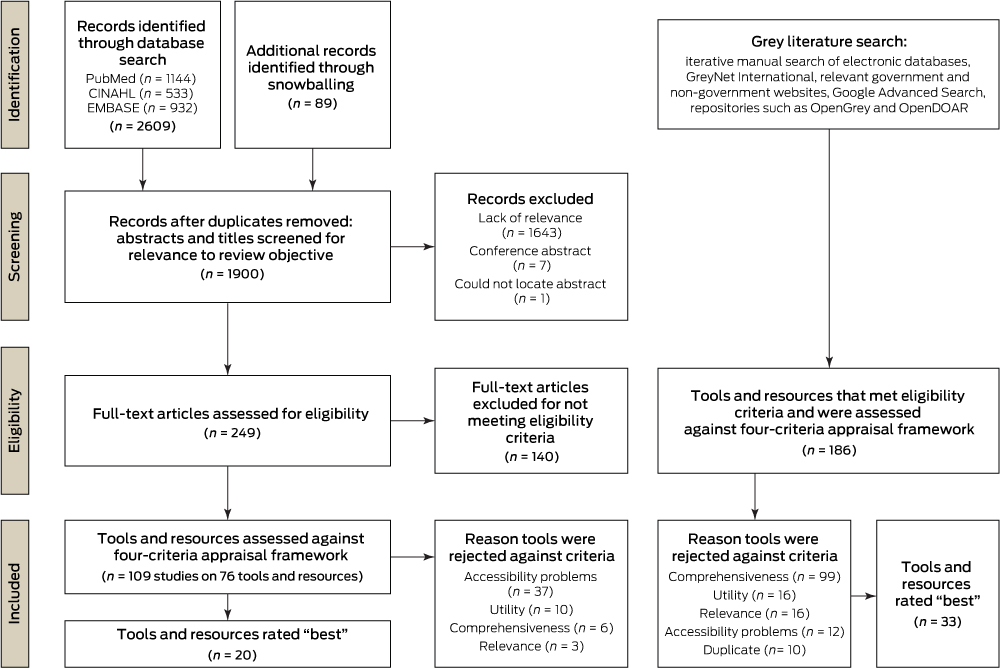

Box 3 shows the mean and range of scores for recommended, rejected and divergent tools and resources in Rounds 1 and 2. Overall, results suggest good concordance in ratings between practice managers and GPs, and clear delineation between recommended and rejected tools and resources. All reviewers provided a recommendation, but not all provided a final score.

Of the final suite of 21 tools and resources (Box 4), five were Australia-specific, six were from the United Kingdom and seven were from North America. Nearly all the tools and resources addressed two or more elements of the PC-PIT, with the most common elements being leadership, change management and patient-centred and community-focused care. Most tools and resources took a whole-of-practice approach and involved most practice staff.

As reviewers perceived the tools and resources to be relevant to different target audiences and PC-PIT elements, only consensus results are reported (ie, where both reviewers in Round 1 indicated the same audience or PC-PIT element for a recommended tool, these are recorded in Box 4; likewise where three or four reviewers indicated the same audience or element in Round 2).

Qualitative results

Key results are summarised below (full details are presented in Appendix 3). Three key themes were common to the recommended tools and resources; namely, that they were: (i) easily used (high utility), (ii) useful to the practice (high value) and (iii) complemented and supported elements of the PC-PIT. Tools and resources were more likely to be scored highly if they had been successfully used on previous occasions by the reviewer(s) or had the perceived potential to be modified or adapted, or if the reviewer indicated an intention to use the tool or resource in the future.

It is beautiful in its simplicity. It is well laid out and easy to use. This can be used easily with minimal training and support. All practice staff should find this easy to use. (GP, Round 1)

A very useful tool to enable change to occur in small managed steps that become improvements, not just changes for the sake of change. A tool that assists in reaching goals and monitoring progress toward the goal. (practice manager, Round 1)

A broad range of limitations with the recommended tools and resources were also noted. GP comments centred mainly on poor utility (too complex or too general), whereas both GPs and practice managers focused on potential implementation challenges, including the need for further resourcing, strong leadership and buy-in from other members of the practice.

It is easy to use and quite simple. It does require a facilitator and team time to be most effective; this can sometimes be difficult to arrange in a busy practice. (practice manager, Round 2)

The six unanimously rejected tools and resources from Rounds 1 and 2 were perceived to have poor utility (hard to follow, too sophisticated, too generalised, too time- and resource-intensive or too wordy); be relevant mainly to hospitals or other non-primary care organisations; be already out of date; require external facilitation; or to be duplicated by or of no additional value to the PC-PIT.

It is not simple to follow. Language is not simple and is too wordy without practical summaries to tie it all in together. It would need extensive facilitation and would achieve minimal practical benefit. (GP, Round 2)

There were 35 tools and resources in Round 1 and 22 in Round 2 to which practice managers and GPs gave divergent or unsure judgements. Most of these tools complemented the PC-PIT, but there were mixed comments on their utility and usefulness, and perceptions of their lack of relevance to the broader Australian context or the context of general practice. If reviewers perceived that the tool replicated the PC-PIT or existing accreditation resources, these were also noted as limitations.

I can’t recommend the tool as is but really recommend the concept. I’ve found it to be excellent in my own practice. It could be worked on to be feasible in Australian general practice through the use of case conferencing items and sponsored workshops which explain how it works. (GP, Round 2)

Overall, the tools and resources accepted in the final suite were perceived to have high utility and relevance, which outweighed any limitations.

This is a well designed resource. A number of the modules would be useful in the Australian setting but some are not — if offered as a resource for PC-PIT, there needs to be an explanation (practice manager, final round)

Tools and resources excluded from the final suite were rejected primarily because they did not fit the Australian context or were too complex. All excluded tools and resources were perceived to have some strengths, but more limitations in relation to utility when compared with the final set of tools and resources.

This is a useful tool but does not fit with Australian general practice training at a practice level. (practice manager, final round)

Discussion

Addressing practice systems is a recognised component of achieving QI in primary care.4,22,35 Our study indicates that potential end users have a preference for tools and resources that cover multiple aspects of practice function. However, issues remain regarding how to promote and sustain QI and the need for ongoing practice support, training and potential financial incentives to undertake and implement QI activities.17

As primary care organisations, health authorities and research networks work to develop QI tools, resources and approaches, our study highlights the need to consider both the capacity of health professionals and practice managers to undertake and drive QI initiatives and their preferences for tools and resources that are most applicable to the context of their practice, including factors that enable (eg, strong leadership, buy-in from others, high relevance) and hinder (eg, implementation cost) tool use.3,16,17,36,37

The final suite of tools and resources included three that were unanimously recommended by the Expert Advisory Panel: Event Analysis: the Seven Steps, the UK National Health Service clinical engagement resources and the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycle. These types of tools and resources are familiar to practices; the PDSA is particularly widely used by both the Australian Primary Care Collaboratives and RACGP QI programs.37,38 Health care professionals demonstrated a clear preference for resources they perceived to be of high utility — those that are simple to understand, easy to use and require no additional training.25 Tools and resources that can be used by all staff and involve all domains of practice operation are considered of highest value, particularly in identifying areas in need of change and in facilitating and monitoring the change process.36 Tested and proven tools and resources (ie, those with high credibility) and those perceived to be easily adapted to suit practice context were judged as most acceptable in our study. Indeed, the credibility of a tool or resource has been linked to greater adherence and implementation, particularly in the use of clinical guidelines.25

However, access to well designed, adaptable tools and resources is only part of the QI process. The acceptability of tools and resources is moderated by considerations relating to implementation and perceptions of the degree of benefit to be gained (perceived value). In this study, reviewers weighed up the costs of implementation (eg, time commitment, the need to pay for external facilitators) against the level of benefit that could potentially be gained. Rejected QI tools and resources were those perceived to be too time-consuming or too complex and thus beyond practice capacity.17,39,40

There has been limited research on appropriate end user-selected tools and resources relevant to general practice. Several of the tools and resources, although not designed for the Australian context, were highly regarded by the Expert Advisory Panel. There is an opportunity to further explore how these tools and resources could be adapted for the Australian primary care context and so provide additional valuable resources to support organisational performance in general practice. Whatever tools and resources are used, QI is a dynamic process and one that often requires the use of more than one QI tool or resource. It requires fostering and sustaining a QI culture, strong team leadership and the implementation of QI at the grassroots level to ensure buy-in, uptake and, ultimately, better quality care.4

Our study had some limitations. While the Delphi technique is a well recognised review method, the judgements of the selected Expert Advisory Panel may not be representative of all end users, and tool or resource acceptability may vary according to the specific interests of individuals. Perceptions of utility may also change with exposure to and increasing familiarity with specific QI tools and resources. However, we endeavoured, through the panel selection process, to engage people with a high level of experience in the field and from a diversity of practices. Our modification of the Delphi technique also limited the number of rounds of review for each of the tools and resources. Ideally, all panel members would have reviewed all tools and resources in each round, but this was not possible due to time constraints and reviewer workloads. We also acknowledge that new QI tools and resources are constantly becoming available and will not have been included in this evaluation, while existing tools and resources can become outdated or difficult to access. It is also likely that several of the excluded tools and resources could be useful for specific tasks in practice, despite their identified limitations.

In conclusion, the final suite of tools and resources to support and enhance the use of the PC-PIT offers one approach to improving the quality of primary care in Australia. Finding ways to integrate and sustain the currency of this resource suite will need the future support of existing peak professional partners, such as the RACGP, the Primary Health Network and the Australian Association of Practice Management. Further work should explore the feasibility of the use of this suite and the potential to modify useful international tools and resources to suit the Australian context.

Box 1 –

Evaluation steps for assessing quality improvement tools and resources

|

|

Step 1

|

Establish Expert Advisory Panel

|

|

|

Define tool and resource review task

|

|

Step 2

|

Develop assessment form

|

|

|

Pilot assessment form

|

|

Step 3

|

Data collection

|

|

|

Three rounds of review of tools and resources

|

|

Step 4

|

Data analysis: qualitative and quantitative

|

|

Step 5

|

Select suite of recommended tools to support PC-PIT

|

|

|

PC-PIT = Primary Care Practice Improvement Tool.

|

Box 2 –

Evaluation process for assessing quality improvement tools and resources

Box 3 –

Review scores for quality improvement tools in Rounds 1 and 2*

|

Score

|

Round 1

|

Round 2

|

|

Recommended (n = 14)

|

Rejected (n = 4)

|

Divergent/unsure (n = 35)

|

Recommended (n = 11)

|

Rejected (n = 2)

|

Divergent/unsure (n = 22)

|

|

|

Total, mean (range)†

|

17 (14–20)

|

5 (5)

|

13 (8–17)

|

16 (12–19)

|

5 (3–6)

|

11 (6–15)

|

|

n = 12

|

n = 2

|

n = 30

|

n = 11

|

n = 2

|

n = 21

|

|

General practitioner, mean (range)‡

|

8 (5–10)

|

1 (0–2)

|

6 (0–10)

|

8 (5–10)

|

2 (0–3)

|

5 (0–10)

|

|

n = 13

|

n = 2

|

n = 33

|

n = 11

|

n = 2

|

n = 21

|

|

Practice manager, mean (range)‡

|

9 (7–10)

|

3 (0–5)

|

7 (0–10)

|

8 (6–9)

|

3 (3)

|

6 (1–10)

|

|

n = 13

|

n = 4

|

n = 32

|

n = 11

|

n = 2

|

n = 22

|

|

|

* All reviewers provided a recommendation, but not all provided a final score. † Score out of 20. ‡ Score out of 10.

|

Box 4 –

Final suite of 21 recommended quality improvement tools and resources

|

Tool name, URL and description

|

Target audience

|

PC-PIT elements

|

Country developed

|

No. who recommended tool (n = 9)

|

|

|

Clinical engagementhttp://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/clinical_engagement.htmlThis suite is designed to engage clinicians at the start of the project to help plan and avoid pitfalls of instigating change.

|

M, N, MG

|

L, CM

|

UK

|

9

|

|

Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) (NHS)http://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/plan_do_study_act.htmlThis tool provides a framework for developing, testing and implementing changes leading to improvement. It can be used to test an idea by temporarily trialling a change and assessing its impact.

|

M, N, MD, MG, AR

|

L, CM, P, IT

|

UK

|

9

|

|

Event Analysis: the Seven Stepshttp://arkiv.patientsikkerhed.dk/media/609926/dsp_laeringssaet_uk_web.pdfThis work provides seven steps to key event analysis in primary care. It was inspired by the NHS Significant Event Audit Guidance for Primary Care.

|

M, N, MG, AR

|

All

|

Netherlands/Belgium

|

9

|

|

Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions (PACIC)http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=PACIC_Survey&s=36The PACIC measures specific actions or qualities of care, congruent with the Chronic Care Model, that patients report they have experienced in the delivery system. It can be used in conjunction with ACIC.

|

P

|

PCC, C

|

US

|

8

|

|

SafeQuest (NHS Education Scotland)http://www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/media/6362/Safety%20climate%20questionnaire%20MASTERCOPY.pdfQuestionnaire (30 items) to measure perceptions of safety climate in primary care. Intended for use by all members of the primary care team. Questions cover workload, communication, leadership, teamwork, safety systems and learning.

|

M, N, MD, MG, AR

|

PCC, C, CM, P, L, G

|

Scotland

|

8

|

|

Quality Improvement Hubhttp://www.qihub.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-learning/qi-e-learning.aspxA suite of 16 e-learning modules to support the quality improvement learning journey. Includes commonly used tools and examples (not all are relevant to the Australian context).

|

M, N, MD, MG, AR

|

L, CM, P, IT

|

Scotland

|

8

|

|

Leanhttp://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/lean.htmlLean is an improvement approach to design or redesign services to ensure that work done adds value to patient care. It links to a number of other change innovation tools (eg, process mapping and the cause and effect diagram).

|

M, N, MD, MG, AR

|

PCC, C, L, G, CM, P

|

UK

|

8

|

|

Plan, Do, Study, Act (RACGP)New title: Putting prevention into practice (“Green Book”, 2006)http://www.racgp.org.au/your-practice/guidelines/greenbookThe PDSA method involves a “trial and learning” approach in which an idea, hypothesis or suggested solution for improvement is made and tested on a small scale before any changes are made to the whole system. It is a cyclical model, allowing improvements to be achieved and refined in one or more cycles.

|

P, M, N, MD, MG, AR

|

All

|

Australia

|

8

|

|

Advanced Access and Efficiency Workbook for Primary Carehttp://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/Documents/qi/qi-aae-interactive-workbook-en.pdfThe workbook outlines fundamental information required to understand the concept of advanced access and efficiency, plus tools, measures and techniques used to assist implementation. Information is presented in a practical format and is backed by the experience of clinicians and change management consultants.

|

MG

|

All

|

Canada

|

7

|

|

RACGP Clinical guidelineshttp://www.racgp.org.au/your-practice/guidelinesLinks to more than 50 endorsed clinical guidelines to assist general practitioners and allied health care staff in their work. Many of these guides also assist with improving practice organisation (eg, Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice).

|

M, N, MG

|

G, C

|

Australia

|

7

|

|

Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (ACIC)http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=Survey_Instruments&s=165Designed to help organisations evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of their delivery of care for chronic illness in six areas: community linkages, self-management support, decision support, delivery system design, information systems and organisation of care. Two versions (ACIC 3.0 and 3.5) are available and may be used in conjunction with PACIC.

|

M, N, MD, MG, AR

|

All

|

US

|

7

|

|

Creativity Toolshttp://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/quality_and_service_improvement_t%20ools/creativity_tools_-_an_overview.htmlCreativity tools are tried and tested ways of coming up with new solutions and perspectives to an issue or problem. These approaches include: brainstorming, six thinking hats, that’s impossible, fresh eyes, wish for the seemingly impossible, simple rules to thinking differently, and the affinity diagram.

|

M, N, MD, MG, AR

|

All

|

UK

|

7

|

|

Pen Computer Systems Clinical Audit Tool (CAT) resourceshttp://www.clinicalaudit.com.au/using-cat/installation-and-user-guidesA data extraction and analysis tool compatible with Best Practice and Medical Director software. It acts as an online clinical audit tool with links to Classic CAT, Cleansing CAT and PAT CAT. The tool enables efficient implementation of clinical interventions, comparison of Medicare Benefits Schedule item number utilisation and identification of at-risk populations.

|

M, N

|

IT

|

Australia

|

6

|

|

Diabetes prevention and management in general practice: using the Pen Computer Systems Clinical Audit Toolhttp://www.diabetesvic.org.au/Advanced-Search-Result-Detail?ocmsLang=en_US&content_id=a1R9000000I9UoyEAFThis resource gives ideas and suggestions on ways of approaching the systematic prevention and management of people with diabetes in order to allow practices to implement and measure change.

|

M, N

|

PCC, G

|

Australia

|

6

|

|

Patient Surveys: Research and Resourceshttp://www.hscr.co.nz/research-and-resourcesThis site provides links to resources, tools and articles including Handbook on improving your practice with patient surveys.

|

MG

|

PCC, C, P

|

New Zealand

|

6

|

|

Primary Care Resources and Supports (PCRS) for Chronic Disease Self Managementhttp://www.diabetesinitiative.org/support/documents/PCRSwithBackgroundandUserGuide.Rev12.08.FINAL.pdfThe PCRS was developed for primary care practices interested in improving self-management support systems and service delivery. It is designed to be used with multidisciplinary teams working together to manage a patient’s health care.

|

M, N, MD

|

PCC, C, P

|

US

|

6

|

|

Protecting your practice informationhttp://www.racgp.org.au/your-practice/ehealth/protecting-informationOnline links related to protecting practice information, including computer and information security standards, using email in general practice, privacy and effective solutions for e-waste.

|

M, N, MD, MG, AR

|

G,C, CM, P, IT

|

Australia

|

6

|

|

Patient Engagement Projectshttp://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/OurImpact/ImpactStories/ImpactStory/2012/10/31/93366af2-5ef7-48df-9a7e-6c98d880e236.aspxThis site links to three innovative patient resources to facilitate the process of patient engagement.

|

M, N, MD

|

PCC, P, C

|

Canada

|

5

|

|

Interpersonal Processes of Care Survey (IPC-29)http://dgim.ucsf.edu/cadc/cores/measurement/ipcindex.htmlThe IPC survey is a patient-reported, multidimensional, 29-item instrument appropriate for patients from diverse racial and ethnic groups. The survey assesses sub-domains of communication, patient-centred decision making and interpersonal style.

|

P

|

PCC, P

|

US

|

5

|

|

Practice Staff Questionnaire (PSQ)http://www.fmdrl.org/index.cfm?event=c.getAttachment&riid=3895The PSQ has been designed and used to gather information about a practice’s culture. It contains 62 statements for staff to indicate their degree of agreement as it applies to their practice. The survey is designed to be completed by all practice staff.

|

M, N, MD, MG, AR

|

L,G, C, CM, P

|

US

|

5

|

|

Health Service Co-Designhttp://www.healthcodesign.org.nzThis resource provides a range of flexible tools for working effectively with patients in service improvement work. While the focus is on patients themselves, the tools can be equally applied to other groups such as frontline staff, family and carers.

|

All

|

All

|

New Zealand

|

5

|

|

|

NHS = National Health Service. PC-PIT = Primary Care Practice Improvement Tool. RACGP = Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. UK = United Kingdom. US = United States. Target audiences: AR = administration/reception. M = medical. MD = multidisciplinary. MG = management. N = nursing. P = patients. All = all the above. PC-PIT elements: C = communication. CM = change management. G = governance (organisational and clinical). IT = information and information technology. L = leadership. P = performance culture. PCC = patient-centred and community-focused care. All = all elements. Web links provided for each tool were current at the time of publication.

|

more_vert

more_vert