The National Emergency Access Target (NEAT) stipulates that a pre-determined proportion of patients should be admitted, discharged or transferred from Australian emergency departments (EDs) within 4 hours of presentation. Targets that varied from state to state were set for all Australian EDs by the National Partnership Agreement in 20121 in response to evidence that ED overcrowding and prolonged length of stay were associated with increased in-hospital mortality.2,3 The original aim was to incrementally increase the target to 90% in all jurisdictions by 2015, in line with the “4-hour rule” target set in the United Kingdom in 2010.

Despite the potentially major impact of the NEAT upon patient care, there was no prospective standardised framework for monitoring outcomes for patients admitted to hospital from EDs. Measuring patient outcomes is difficult, and no approach is beyond criticism. The hospital standardised mortality ratio (HSMR) is an objective screening tool designed to alert clinicians to potentially avoidable harm, and it has been accepted as a core indicator of hospital safety.4 The HSMR compares the numbers of observed and expected deaths; unlike raw mortality statistics, it excludes the deaths of palliative care patients, and attempts to adjust for clinically relevant risk factors, such as age, sex and principal diagnosis. The HSMR has been clinically useful in Australia, where it has helped guide the clinical re-design of ED admission processes,5,6 and in the UK, where elevated HSMRs helped identify potentially avoidable adverse clinical events in Mid Staffordshire Trust hospitals.7

Retrospective studies in large hospitals in Brisbane,5 Melbourne8 and Perth9 have shown that clinical restructuring induced by the NEAT has been associated with reduced ED crowding, improved patient flows through the ED, and reduced in-hospital mortality. In one study, a rise in NEAT compliance rates from 30% to 70% was strongly correlated with a reduction in HSMR for patients specifically admitted from the ED (eHSMR), from 110 to 67 (R = 0.914, P < 0.001).6

However, certain factors may have confounded these findings. Following the introduction of the NEAT, more low acuity patients, who are less likely to die, may have been admitted to short-stay wards instead of being discharged from the ED more than 4 hours after presenting. This would introduce a bias if risk adjustment were to overestimate the mortality risk of these low risk patients. In addition, increased coding of patients as receiving palliative care after acute admission would increase the number of expected deaths, while the number of observed deaths would remain unchanged, again reducing the eHSMR.10

Putting these interpretive considerations to one side, no hospital in Australia, apart from small rural institutions, has consistently reached 4-hour targets greater than 85%.11 Moreover, despite evidence associating ED overcrowding with increased in-hospital mortality, and reduced mortality in some jurisdictions after introducing a time-based target, uncertainty persists as to whether such targets consistently improve patient outcomes in most hospitals.

Overzealous pursuit of stringent time-based targets may actually compromise quality of care and endanger patient safety. This was seen in the Mid Staffordshire experience in the UK, where elevated HSMRs suggested that avoidable patient harm may have increased after introducing time-based treatment targets.7 A focus on the NEAT must be coupled with patient-centred outcome measures that balance the dual needs for hospital efficiency and safe, effective care.2,3,6,8,9,12,13 The ideal NEAT compliance rate maximises the benefits of decongesting EDs while minimising the potential harms of rushed and suboptimal management of acutely ill patients, and has not yet been determined on the basis of empirical data. A recent literature review of 4-hour targets in Australia and the UK noted that all were arbitrary and lacked validation.14 Another review concluded that the introduction of the 4-hour rule in the UK, undertaken at considerable financial cost, had not resulted in consistent improvements in care, with markedly varying effects between hospitals reported.15 In Australia, the need to determine the optimal NEAT has increased because of the opportunity costs involved in achieving high compliance rates and the loss of financial incentives following dissolution of the National Partnership Agreement in 2014.16,17

The aims of our study were to explore the relationship between eHSMR and NEAT compliance rates using a large dataset from several Australian hospitals, and to assess the effects on this relationship of potential confounding by the inclusion of palliative care and short-stay patients.

Methods

Study design, participating sites and data sources

This retrospective observational study covered the 4-year period from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2014, spanning the introduction and subsequent focus on the NEAT by Australian governments after signing the National Partnership Agreement on Improving Public Hospital Services in February 2011.1

De-identified data on hospital admissions during the study period were obtained from The Health Roundtable (HRT) in accordance with its academic research policy. The final dataset comprised data from 59 Australian hospitals; all 33 New Zealand hospitals, which were working towards a 6-hour target, were excluded, as were 26 sites in Australia with no general EDs, two specialist hospitals with an atypical mortality profile, and 48 hospitals for which the ED data for the study period were incomplete. With approval from the HRT, the de-identified dataset was independently analysed by investigators from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) e-Health Research Centre.

Episodes of care and patient cohorts

All patients who presented to an ED of one of the study hospitals and were either admitted to or discharged from the hospital were included in the analysis. For admitted patients, the unit of analysis was the entire hospital stay, preserving any changes in care type during the admission. Elective patients, patients coded as dead on arrival and who had a principal diagnosis of sudden unexplained death or had died in the ED, organ donation episodes, non-acute and geriatric evaluation and management episodes, and all episodes involving neonates were excluded. Patients coded as palliative and short-stay patients (defined as being an inpatient for less than 24 hours) were also excluded from the primary analysis.

In addition, three additional patient cohorts were analysed:

-

patients coded as palliative care patients at the time of death;

-

patients with short stays (defined as a length of hospital stay of less than 24 hours), this cohort serving as a proxy group for patients admitted to short-stay observation wards or clinical decision units, and thereby compensating for inconsistencies between hospitals in coding transfers to these wards as inpatient admissions; and

-

these two cohorts combined.

NEAT compliance rates

The NEAT compliance rate was defined as the proportion of patients with an ED length of stay of less than 4 hours. The rate was calculated separately for all patients (total NEAT) and for patients admitted to inpatient units and designated short-stay units (admitted NEAT).

Main outcome measure

The main outcome measure was the relationship between NEAT compliance rates and inpatient mortality for emergency admissions, as expressed by the eHSMR. The eHSMR was preferred to raw mortality rates for two reasons:

-

The HSMR is the risk-adjusted ratio of the observed to the expected numbers of deaths, which helps account for variations in the acuity of presentations and in hospital activity.

-

The HSMR has been validated in other clinical studies for monitoring patient outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Regression models of eHSMR

Several models were used to calculate the expected number of deaths for the denominator of the eHSMR. In keeping with standard practice,18,19 the data on all included patients were separated into two parts: episodes coded with the top 68 diagnostic codes, which account for 80% of in-hospital deaths (part 1), and episodes accounting for the remaining 20%, whereby the number of individual International Classification of Diseases, revision 10 (ICD-10) codes was reduced from about 1000 to ten broad categories based on the raw proportions of deaths associated with each code (part 2). Model selection for each part consisted of an elastic net model with tenfold cross-validation, with the chosen penalty parameter being the largest λ within one standard deviation of the minimum.20 All models initially included two-way variable interactions. Additional information about the modelling process is available in Appendix 1. Area under the curve measures assessed the predictive ability of the model, with values of 0.85 found for the part 1 model and 0.89 for part 2. Similar values were found for models of the three additional cohorts described above.

Relation between NEAT compliance rates and eHSMR

Emergency presentation data, and observed and expected in-hospital mortality rates were aggregated at monthly levels for each hospital and for each hospital peer group over the study period. Overall NEAT and admitted NEAT compliance rates and eHSMR were then calculated. Exploratory data analysis with linear regression models suggested a complex relationship between NEAT and eHSMR, and non-linear relationships were assessed using a restricted cubic spline with knots at 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 85%, 90% and 95% NEAT compliance rates.

The primary analysis of the NEAT–eHSMR relationship excluded palliative care and short-stay patients; the effects on this relationship of including these patient cohorts were explored in sensitivity analyses of the total cohort and each hospital peer group. Statistical analyses were undertaken in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing); P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Ethics approval

An ethics approval exemption was provided by the Metro South Health Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, HREC/15/QPAH/233).

Results

Participating sites

Emergency presentation and admissions data and operating characteristics of the participating hospitals are summarised in Appendix 2, Table 1. ED and inpatient data were aggregated for 12.5 million ED episodes of care and 11.6 million inpatient episodes of care.

NEAT compliance rates

Over the 4-year study period, there was a progressive increase in mean monthly NEAT compliance rates for admitted (25% to 45%), total (56% to 70%) and non-admitted patients (70% to 80%) (Appendix 2, Figure 1).

Relationship between eHSMR and NEAT compliance rates

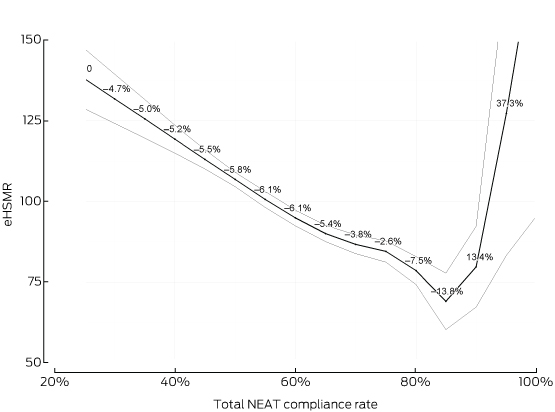

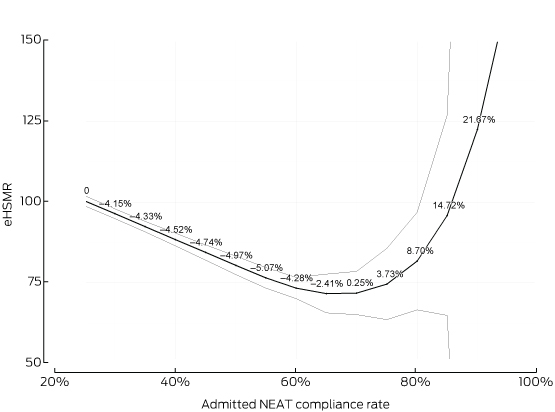

The primary analysis of monthly plots of eHSMR v total NEAT compliance rate (Box 1) and of eHSMR v admitted NEAT compliance rate (Box 2) for all hospitals combined showed similar and significant (P < 0.001) inverse linear relationships until an inflection point was reached. Wide confidence intervals beyond these points reflect the fact that limited data were available.

The eHSMR declined by an average of 5.5% for each five percentage point change in total NEAT compliance rate, reaching a nadir of 73 at a compliance rate of about 83% (range [distance between the two knots in the spline analysis], 80–85%). For admitted NEAT compliance, which included short-stay ward admissions, the eHSMR declined by an average of 4.5% for each five percentage point change in the compliance rate, reaching a nadir of 73 at a compliance rate of about 65% (range, 60–70%).

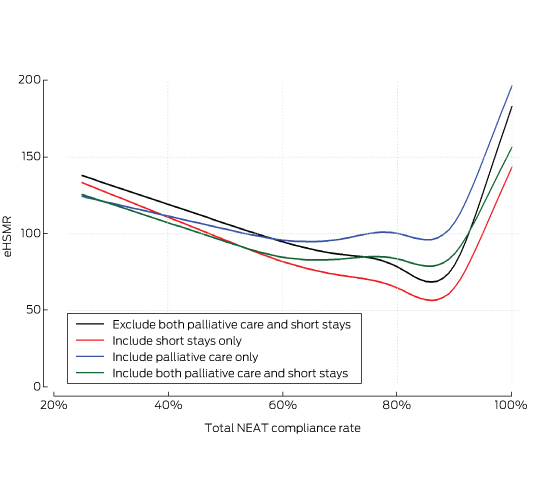

Sensitivity analyses

When the primary analysis was repeated but including either palliative care or short-stay patients, or both, the previously noted relationships between eHSMR and total NEAT compliance were largely unchanged (Box 3).

Discussion

Overview of findings

With the recent abolition of the NEAT, the future of time-based targets for emergency care is unclear. Ours is the first multisite study to assess the relationship between NEAT compliance rates and risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality. An inverse linear relationship was seen as NEAT compliance rates increased to approximately 83% for total NEAT compliance and to 65% for admitted NEAT compliance. Differences between hospitals in the coding of palliative care patients or in the numbers of short-stay patients did not affect the eHSMR–NEAT compliance rate relationships.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study has several strengths. First, the analysis involved a very large number of episodes of care over 4 years from a large, representative sample of Australian hospitals, including the 79% of all tertiary hospitals that account for more than 85% of all ED admissions. Second, we were able to use an objective measure of mortality for emergency admissions to hospital and to assess patient outcomes over the period in which the NEAT was introduced. This study helps inform the debate about whether time-based targets should be retained, and, if so, what they should be.

Limitations of the study include the fact that this was an observational study. We identified a reduction in eHSMR as NEAT compliance rates increased to certain values, but this does not prove causality. However, the relationship was highly significant, even in sensitivity analyses that accounted for potential confounders, and we are unaware of any other national hospital quality and safety initiative implemented during the study period. Our omission of some hospitals limits the generalisability of our findings to all institutions. As the primary outcome measure, the eHSMR does not encompass other outcomes important to patients, such as morbidity or quality of life. Further, the use of HSMRs as the basis for cross-sectional, inter-hospital comparisons is controversial.21 Our final models cannot account for errors associated with estimating HSMRs; the denominator is estimated by modelling, and will therefore be imprecise.19 However, the HSMR is objective, accepted as a national measure,4 and serves as a useful indicator of potentially avoidable mortality within individual hospitals when tracked over time, provided there are no major changes in coding practices or admission policies; this applied to our study.21 Finally, the 95% confidence intervals around the mean eHSMR values corresponding to higher NEAT compliance rates broadened as the number of hospitals achieving such rates decreased, so that it is possible that mortality may further decline at higher NEAT compliance rates.

Implications for clinical practice and policy

We found that there is no robust evidence regarding a clinically significant mortality benefit associated with total and admitted NEAT compliance rates above 83% and 65% respectively. Further, as the identified reduction in mortality for admitted patients was associated with increasing total and admitted NEAT compliance rates, it can be argued that both compliance rates should be monitored. Finally, consideration should be given to embedding time-based NEAT compliance rates within a suite of patient-focused outcome measures that can quickly signal any unintended adverse consequences of pursuing ever higher NEAT compliance rates.

Box 1 –

Total National Emergency Access Targets (NEAT) compliance and hospital standardised mortality ratio for patients admitted from emergency departments (eHSMR) for 59 Australian hospitals, 1 July 2010 – 30 June 2014

Box 2 –

Admitted National Emergency Access Targets (NEAT) compliance and hospital standardised mortality ratio for patients admitted from emergency departments (eHSMR) for 59 Australian hospitals, 1 July 2010 – 30 June 2014

Box 3 –

Effects of potential confounders (palliative care and short-stay patients) on relationship between total National Emergency Access Targets (NEAT) compliance and hospital standardised mortality ratio for patients admitted from emergency departments (eHSMR) for 59 Australian hospitals, 1 July 2010 – 30 June 2014

more_vert

more_vert