Health systems around the world are facing the twin pressures of increasing demand for services, caused by the impact of ageing populations and medical science developments, and a lack of resources as a consequence of economic slowdown in many countries.1 In these circumstances, it should not be surprising that there is an increased focus on using available resources to deliver high quality care and addressing variation in the provision, uptake and costs of health care2 with a view to identifying and reducing unwarranted variation.

The ubiquity of recognition of variation3–5 continues to raise the profile of variation, capturing the imagination of researchers and policy makers6 to pose a challenge to those planning and delivering health care. That challenge runs much deeper than the undemanding observation and recording of variation, to one which must stimulate clinicians, managers and patient groups across the health care system into urgent and necessary action to identify and reduce unwarranted variation. That action is essential, not only as a means of enabling the health care systems to close their funding shortfalls, but more importantly to reduce harm to patients, improve the quality of services and increase value from resources. This is the focus of the NHS Right Care initiative (www.rightcare.nhs.uk) and the genesis of the NHS Atlas of Variation series in England.

The NHS Atlas of Variation series

The NHS Atlas series is a comprehensive view of health care from a geographic perspective, principally using formal NHS administrative organisations to measure a range of indicators including spend and outcomes. The work to produce the NHS Atlas series was greatly influenced by the philosophy and experience of Professor John Wennberg of Dartmouth College in the United States, who knew the full impact of publishing variation and the concept of unwarranted variation, which he defined as “variation in the utilization of health care services that cannot be explained by variation in patient illness or patient preferences”.7

The first Atlas was produced in 2010, and was followed by a series of themed Atlases and two other compendium Atlases (Box 1). NHS England is not alone in producing an atlas of variation; a number of other countries are following the lead from America, Canada and Spain, including Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and New Zealand.

Preparation phase

There are as many lessons to learn from the pre-publication phase of the Atlas series as there are in the post-publication phase. The first lesson is the need for engagement and sponsorship from the very “top of the office”, from both policy makers and senior clinicians. That support is critical to the credibility and sustainability of Atlas production and necessary to mitigate any undue political or managerial interference regarding the main purpose of the Atlases. The Atlas editorial team was convinced that the publication of the Atlas series was much more than just about assisting the NHS deal with the increasing need and demand, which is rising faster than the resources available or the political challenges of the day; namely, meeting targets too frequently designed around organisational objectives not patient need. As important as they may be, it was considered that the publication of the Atlas series is an essential process to jolt the culture of health care away from assuming that existing patterns of care are right and that more resources are always required to improve outcomes. We knew that the culture of the medical and nursing professions, and the behaviours within the NHS, would need to change. The Atlases were designed for emotional impact as well as the transmission of information to prompt all clinicians in primary and secondary care to work together with their population to agree what services should look like, what needs to stop and what services need to start doing to provide higher value health care.

The second lesson from this phase is to remember that the purpose of sharing data on variation is not to claim what is the right or wrong rate of, say, an intervention, but to stimulate the discussion and to prompt the search for unwarranted variation, where resources are being wasted and shift those resources to more appropriate care where patients and the population achieve better outcomes. Indeed, we are reminded that it is not right to use variation data alone to determine which rate is “right” but should acknowledge that the presence of too much variation is a sign of health service delivery problems.8 These are two fundamental concepts and the Atlas production team frequently challenges itself about the use of data, how those data should be presented and to be clear about what it signals.

A way of mitigating that issue introduces the third lesson. It is critical to engage and maintain a constructive relationship with the most senior clinical leaders — in the case of NHS England, the National Clinical Directors (NCDs). This is important when selecting the indicators and agreeing the commentary for the Atlas. The leadership shown from NCDs in NHS England cannot be underestimated and should never be undervalued as an important step in the process of deciding which indicators and which dataset should be applied and what narrative to transmit. This positive relationship also enhances the credibility of the Atlas and increases the focus of attention to those indicators that have been declared as being of such importance by the NCDs, which can also lead to improved uptake and use of the Atlas series through the medium of both the printed versions and the interactive Atlases. These early lessons endorse the notion that stimulating interest and curiosity is the first step toward action and a reduction in unwarranted variation.

Publication phase

It is important to be clear that the publication of the Atlas of Variation is not a blunt performance tool, and the Atlas team is careful not to use any data that the health system does not already have access to. Therefore, available data are always used, in a novel way, to produce commentaries and illustrations, with maps, about the extent of variation for all sorts of provision, spend and outcome. The lesson is that the publication of the maps needs to be both stimulating and dramatic to draw a response from the health care system to investigate the known variation in each area of health care; an objective which appears to be achieved by organisations’ inquisitiveness to understand their position in relation to their peers and then to use that information as formative learning9 for future planning and decision making.

A key message from this phase is the involvement and engagement of other stakeholders, beyond the NCDs, in both the preparation and participation of the launch of the Atlas. It has previously been declared that the engagement of senior clinicians and policy makers is an important part of the whole process, particularly during the publication process. There are other key stakeholders to engage here too; perhaps the most important are patient representative groups and third sector organisations that can create a powerful and positive narrative about what the Atlas is displaying, remembering the message that not all variation is bad — if it were, it would be easier to take action.10 The involvement of patient representatives also helps the shared decision making (SDM) agenda, which is an important part of the transformation process, enabling the active involvement of patients with their clinicians to make the right decision about the choice of treatment.

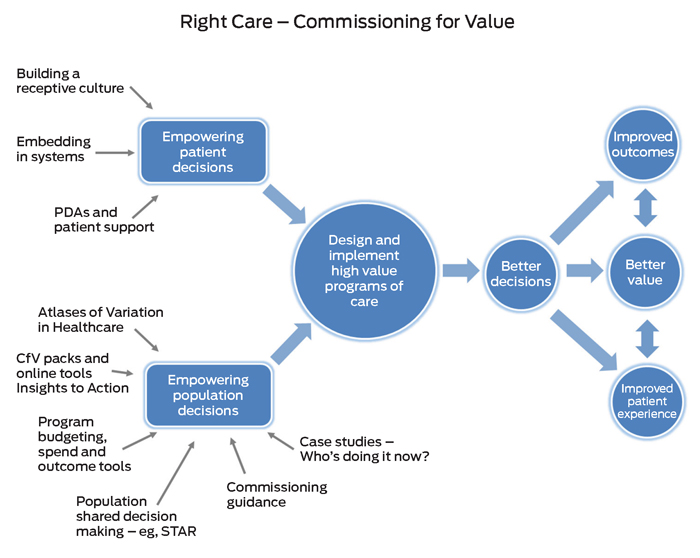

NHS Right Care has long advocated and continues to promote the use of SDM as a way of empowering patients to become part of the solution to the challenge of delivering high quality care. The transformational program has developed and published 35 patient decision aids (PDAs) to complement the Atlas series. PDAs are specially designed resources to help patients make informed decisions about their care. People who have used the PDAs report that they understand their problem and the choices they have more clearly.

The ambition of NHS Right Care is to use the Atlas of Variation to stimulate a search for unwarranted variation in the NHS and its underlying causes, by providing a tool for learning and exploration of potential deficits in local resource allocation. That ambition is amplified when using the PDAs as a tool to engage and support patients in decision making about what is right and appropriate for them.

Public services, including health services, are under pressure to control increasing costs, and the NHS has been challenged to adapt to evolving demands and “shine a light on variation in care and unacceptable practice”11 to improve the quality and safety of care. A significant lesson is that the production and publication of an atlas of variation is not an end in itself but an essential component of a large scale transformation initiative to increase value, improve quality and reduce harm.

Next phase

The domains of quality and safety have strongly influenced the shape and delivery of the NHS for more than a decade, but is this the right paradigm for the next decade and beyond? We ask this as we are reminded that the issue of variation in health care is not a new phenomenon. Indeed, it could be argued that variation has been met with a level of inertia and confusion for many years and by raising the awareness of variation, through the publication of the NHS Atlas of Variation series, we aim to stimulate the search for unwarranted variation but also to further advance the focus of attention toward value.

If health care systems are to meet rising demand with reducing resources, there needs to be a shift from traditional patterns of planning and contracting around established organisations and clinical processes to one that is focused on “doing the right thing — for the right patient — at the right time”, where we need to think about value. The Right Care initiative has set out to promote value by encouraging organisations to aim for optimal care, declaring that it is not a process that can be done in isolation of other organisations, and to remember that no one professional group has all the necessary information or knowledge to plan and deliver optimal care.

Rather, health care systems need to look at their processes, working with their populations to decide if the balance is right between prevention, screening, diagnosis, intervention and long term care. The search for unwarranted variation plays an important part in that quest and the time has arrived for us to enter the “value era”, in which a population perspective and patient views of value are adopted to improve the health outcomes for both populations and individual patients.

Reducing variation to increase value

Possibly the simplest way to think of value is from an economic perspective. The word “value” is, like many words, slippery to define and can have a range of meanings to different people. In the plural, as in the terms “values”, the word has a moral meaning — for example, “we value diversity and equality.” In the singular, however, the meaning is largely economic.

The Right Care approach identifies three types of value:

-

Allocative value — to optimise allocative efficiency by taking responsibility for the resources allocated.

-

Technical value, or efficiency — it is essential that all organisations work across the health care system to maintain a good understanding of what is being delivered, including whether some services are now being delivered at a rate that could be classified as overuse.

-

Personalised value — determined by the degree to which the outcome relates to the particular problem that the individual brought to the health service, where shared decision making becomes the norm for that population.

The primary focus of the Atlas series has been to create a tool to raise the profile of variation, at a population level, as part of a much bigger transformation initiative. What quickly emerged was the need to think of both population and personalised health care as being two sides of the one coin. The agenda now is to focus on increasing the value of health care to the whole population as well as on the optimal care for the individual patient. This is summarised in the Right Care approach (Box 2), which clearly offers an insight into why atlases of variation are important, but recognises that they cannot be the singular answer to transforming health care.

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated how the production and publication of an atlas of variation can be an important step in the journey toward increasing value in health care — for patients, for populations and by directing resources to higher value health care, for tax payers. The article has described how the preparation stage, which includes many conversations, negotiations and lengthy discussions (eg, deciding the indicators and narrative) leads to improved engagement of all stakeholders. Working hard to build a positive relationship at the preparation stage pays dividends during the publication phase, where all stakeholders can contribute to the overall message and purpose of the Atlas. It is not sufficient, however, to publish an atlas of variation in isolation from other tools (eg, patient decisions aids) and expect it to have remarkable impact. An atlas of variation needs to be an integral part of a larger transformational change program.

Box 1 –

NHS Atlas of Variation series titles

|

Year |

Title |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

2010 |

NHS atlas of variation in healthcare |

||||||||||||||

|

2011 |

NHS atlas of variation in healthcare 2.0 |

||||||||||||||

|

2012 |

NHS atlas of variation in healthcare for children and young people |

||||||||||||||

|

2012 |

NHS atlas of variation in healthcare for people with diabetes |

||||||||||||||

|

2012 |

NHS atlas of variation in healthcare for people with kidney disease |

||||||||||||||

|

2012 |

NHS atlas of variation in healthcare for people with respiratory disease |

||||||||||||||

|

2013 |

NHS atlas of variation in healthcare for people with liver disease |

||||||||||||||

|

2013 |

NHS atlas of variation in diagnostic services |

||||||||||||||

|

2015 |

NHS atlas of variation in healthcare 3.0 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert