Health practitioners are often well placed to identify colleagues who pose risks to patients, but they have traditionally been reluctant to do so.1–4 Since 2010, laws in all Australian states and territories require health practitioners to report all “notifiable conduct” that comes to their attention to the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA).

Legal regimes in other countries, including New Zealand,5 the United States3,6 and Canada,7 mandate reports about impaired peers in certain circumstances. However, Australia’s mandatory reporting law is unusually far-reaching. It applies to peers and treating practitioners, as well as employers and education providers, across 14 health professions. Notifiable conduct is defined broadly to cover practising while intoxicated, sexual misconduct, or placing the public at risk through impairment or a departure from accepted standards. Key elements of the law are shown in Box 1.

Mandatory reporting has sparked controversy and debate among clinicians, professional bodies and patient safety advocates. Supporters believe that it facilitates the identification of dangerous practitioners, communicates a clear message that patient safety comes first,8 encourages employers and clinicians to address poor performance, and improves surveillance of threats to patient safety. Critics charge that mandatory reporting fosters a culture of fear,9 deters help-seeking,10 and fuels professional rivalries and vexatious reporting.11,12 Concerns have also been raised about the subjectivity of reporting criteria.13 The Australian Medical Association opposed the introduction of the mandatory reporting regime for medical practitioners, citing several of these objections.14

Little evidence is available to evaluate the veracity of these different views. We sought to provide baseline information on how the regime is working by analysing an early sample of mandatory notifications. Specifically, we aimed to determine how frequently notifications are made, by and against which types of practitioners, and about what types of behaviour.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review and multivariate analysis of all allegations of notifiable conduct involving health practitioners received by AHPRA between 1 November 2011 and 31 December 2012. The Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Melbourne approved the study.

Data sources

We obtained data from two AHPRA sources: mandatory notification forms and the national register of health practitioners.

AHPRA receives notifications on a prescribed form. Notifiers may access the form on AHPRA’s website or by calling a notifications officer on a toll-free number. Two of us (M M B, D M S) helped AHPRA develop the form in 2011. It includes over 40 data fields; most fields have closed-ended categorical responses, but there is also space for free-text descriptions of concerns. Notifiers may append supporting documentation such as medical records and witness statements.

We obtained PDF copies of all notification forms received in five states and two territories between 1 November 2011 and 31 December 2012. Reports from New South Wales were not included. Although health practitioners in NSW are subject to the same reporting requirements as those in other states, AHPRA has a more limited role in relation to notifications made in NSW: when AHPRA receives such notifications, they are referred to the NSW Health Care Complaints Commission to be handled as complaints. AHPRA cannot log and track these notifications in the same way as it can notifications arising in other jurisdictions.

Data collection

We collected data onsite at AHPRA’s headquarters in Melbourne from April 2013 to June 2013. Three reviewers were trained in the layout and content of the notification forms, the variables of interest, methods for searching the health practitioner register, and confidentiality procedures. For each form lodged during the study period, the reviewers extracted variables describing the statutory grounds for notification, type of concern at issue, and characteristics of the practitioner who made the notification (“notifier”) and the reported practitioner (“respondent”). We also coded a variable classifying the relationship of the notifier to the respondent (treating practitioner, fellow practitioner, employer, education provider). Practitioner-level variables extracted from the notification forms were cross-checked with information recorded on the register.

One of AHPRA’s core functions is to maintain a national register of licensed health practitioners. To enable calculations of notification rates, AHPRA provided a de-identified practitioner-level extract of the register as at 1 June 2013. The extract consisted of variables indicating practitioners’ sex, age and profession, and the postcode and state or territory of their registered practice address. Practitioners from NSW and those with student registration were excluded to ensure that the register data matched the sample of notifications. Postcodes were converted to a practice location variable with three categories (major cities, inner and outer regional areas, and remote and very remote areas), based on the Australian Statistical Geography Standard.15

Analyses

We calculated counts and proportions for characteristics of notifications, notifiers and respondents. We also calculated frequency of notification according to the professions of the notifiers and respondents, respectively.

We used multivariable negative binomial regression to calculate incidence of notifications by five respondent characteristics: profession, sex, age, state or territory, and practice location. Incidence measures reported for each characteristic were adjusted for the size of the underlying population and all other observed characteristics. Details of the calculation method and regression results are provided in the Appendix.

All analyses were done using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp).

Results

AHPRA received 850 mandatory notifications during the study period. After excluding notifications relating to nine practitioners from NSW and 22 students, our sample consisted of 819 notifications. The median time between the alleged behaviour and its notification to AHPRA was 18 days (interquartile range, 5 to 58 days).

Grounds and conduct

The distribution of notifications by statutory ground and type of concern, with examples, is shown in Box 2. This information was available for 811 of the 819 notifications. Sixty-two per cent were made on the grounds that the practitioner had placed the public at risk of harm through a significant departure from accepted professional standards; 17% alleged that the practitioner had an impairment that placed the public at risk of substantial harm (more than half of these related to mental health); 13% alleged that the respondent had practised while intoxicated; and 8% related to sexual misconduct (most commonly a sexual relationship between the practitioner and a patient).

Characteristics of notifiers and respondents

The characteristics of notifiers and respondents are shown in Box 3. Nurses and doctors dominated notifications, with 89% of all notifications (727/819) involving a doctor or nurse in the role of notifier and/or respondent. Nurses and midwives accounted for 51% of notifiers and 59% of respondents. Doctors accounted for 29% of notifiers and 26% of respondents.

Men constituted 37% of notifiers and 44% of respondents. Eighty per cent of notifications were about practitioners in three jurisdictions: Queensland (39% [321/819]), South Australia (22% [184/819]), and Victoria (18% [150/819]).

Nexus between notifiers, respondents and conduct

Among the 731 notifications for which it was possible to identify the professional relationship between the notifier and the respondent, 46% were made by fellow health practitioners (ie, health professionals other than the respondents’ treating practitioners) (Box 3). Forty-six per cent of notifications were made by the respondents’ employers; this included cases in which the notifier was also a registered health practitioner (eg, medical director of a hospital) but the notification was made in an employer rather than individual capacity.

Among 736 notifications for which it was possible to tell how the respondent’s behaviour came to the attention of the notifier, the conduct was directly observed by the notifier in about a quarter of cases (201/736). In more than half of notifications (376/736), the conduct at issue came to the notifier’s attention through a third party — the patient, a colleague or some other person. For the remainder, the conduct was either identified through an investigatory process such as a record review, clinical audit, or police or coronial investigation (81/736) or self-disclosed by the respondent (78/736).

Intraprofessional and interprofessional notifications

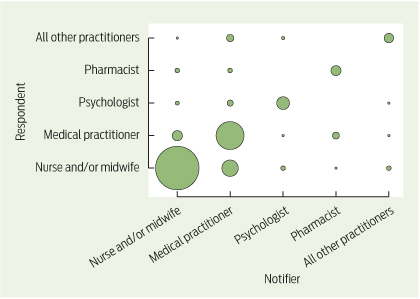

Among 697 notifications for which it was possible to determine the profession of the notifier and the respondent, the profession of the notifier and respondent was the same in 80% of cases (557/697). This concentration of intraprofessional notifications is depicted in Box 4 by the diagonal line of relatively large bubbles running from the bottom left to the top right of the figure. Nurse-on-nurse notifications (those involving nurses and/or midwives) and doctor-on-doctor notifications accounted for 73% (507/697) of notifications.

Interprofessional notifications mostly involved doctors notifying about nurses (7% [51/697]) and nurses notifying about doctors (3% [20/697]). The remainder were widely distributed across other interprofessional dyads.

Incidence of notifications

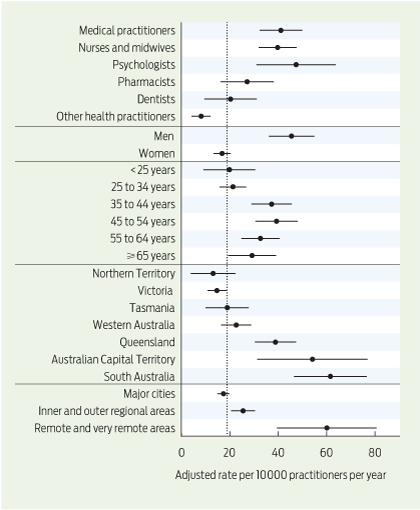

The unadjusted incidence of mandatory reporting was 18.3 reports per 10 000 practitioners per year (95% CI, 17.0 to 19.6 reports per 10 000 practitioners per year). Adjusted rates of notification for the five respondent characteristics analysed are shown in Box 5. Psychologists had the highest rate of notifications, followed by medical practitioners, and then nurses and midwives (47.4, 41.1 and 39.7 reports per 10 000 practitioners per year, respectively).

The incidence of notifications against men was more than two-and-a-half times that for notifications against women (45.5 v 16.8 reports per 10 000 practitioners per year; P < 0.001). Health practitioners working in remote and very remote areas had a much higher incidence of notification than those in major cities and regional areas (60.1 v 17.4 and 25.5 reports per 10 000 practitioners per year). There were also large differences in incidence of notifications across jurisdictions, ranging from 61.6 per 10 000 practitioners per year in South Australia to 13.1 per 10 000 practitioners per year in the Northern Territory.

Discussion

We found that perceived departures from accepted professional standards, especially in relation to clinical care, accounted for nearly two-thirds of reports of notifiable conduct received by AHPRA during the study period. Nurses and doctors were involved in 89% of notifications, as notifiers, respondents or both. Interprofessional reports were uncommon. We observed wide variation in reporting rates by jurisdiction, sex and profession — for example, a nearly fivefold difference across states and territories, and a two-and-a-half times higher rate for men than for women.

Our results suggest that some of the harms predicted by critics of mandatory reporting and some of the benefits touted by supporters are, so far, wide of the mark. Concerns that mandatory reporting would be used as a weapon in interprofessional conflict should be eased by the finding that the notifier and respondent were in the same profession in four out of five cases. Indeed, the low rate of notifications by nurses about doctors (3%) gives rise to the opposite concern. Although nurses are often well placed to observe poorly performing doctors, our data suggest that the new law has not overcome previously identified factors that may make it difficult for nurses to report concerns about doctors.2

On the other hand, supporters of mandatory reporting who heralded it as a valuable new surveillance system may be concerned by the low rates of reporting in some jurisdictions. Part of the variation in incidence of notifications across jurisdictions that we observed might reflect true differences in incidence of notifiable events, but it is also likely that differences in awareness of reporting requirements and differences in notification behaviour contribute to the variation. US research suggests that underreporting of concerns about colleagues is widespread, even when mandatory reporting laws are in place.3 The identified barriers to reporting fall primarily into four categories: uncertainty or unfamiliarity regarding the legal requirement to report; fear of retaliation; lack of confidence that appropriate action would be taken; and loyalty to colleagues that supports a culture of “gaze aversion”.2,3,16–18 Action to better understand and overcome these barriers could be aimed at jurisdictions with the lowest reporting rates.

The higher rate of notification for men that we observed is consistent with previous research showing that male doctors are at higher risk of patient complaints,19,20 disciplinary proceedings21 and malpractice litigation.22 While systematic differences in specialty and the number of patient encounters may explain some of the heightened risk observed for men, other factors, such as sex differences in communication style and risk-taking behaviour,23,24 are probably also in play.

The main strength of our study is that we included data from every registered health profession and all but one jurisdiction. The ability to access multistate data for research and evaluation purposes is an important benefit of Australia’s new national regulation scheme, and would not have been possible 5 years ago. Other federalised countries with siloed regulatory regimes continue to struggle with fragmented workforce data.

Our study has three main limitations. First, because mandatory reporting was implemented in concert with other far-reaching changes to the regulation of health practitioners, it was not possible to compare the incidence of notifications before and after the introduction of the new law. Second, it was not feasible to include information on the outcomes of notifications: too small a proportion of notifications had reached a final determination at the time of our study to provide unbiased data. As the scheme matures, it would be useful to explore what proportion of reports were substantiated and resulted in action to prevent patient harm, at an individual or system level. Third, our analysis did not include notifications against practitioners based in NSW.

This study is best understood as a first step in establishing an evidence base for understanding the operations and merits of Australia’s mandatory reporting regime. The scheme is in its infancy and reporting behaviour may change as health practitioners gain greater awareness and understanding of their obligations. Several potential pitfalls and promises of the scheme remain to be investigated — for example, the extent to which mandatory reporting stimulated a willingness to deal with legitimate concerns, as opposed to inducing an unproductive culture of fear, blame and vexatious reporting. Qualitative research, including detailed file reviews and interviews with health practitioners and doctors’ health advisory services, would help address these questions. Further research should also seek to understand the relationship between mandatory reports and other mechanisms for identifying practitioners, such as patient complaints, incident reports, clinical audit, and other quality assurance mechanisms.

1 Elements of mandatory reporting law for health practitioners in Australia

Who can be subject to a report?

All registered health practitioners in Australia (doctors, nurses, dentists and practitioners from 11 allied health professions)*

Who has an obligation to report?

Employers, education providers and health practitioners†

What types of conduct trigger the duty to report?

The practitioner: (a) practised the profession while intoxicated by alcohol or drugs, (b) engaged in sexual misconduct in connection with the practice of the profession, (c) placed the public at risk of substantial harm in the practice of the profession because of an impairment, or (d) placed the public at risk of harm by practising in a way that constitutes a significant departure from accepted professional standards

What is the threshold for reporting?

Reasonable belief that notifiable conduct has occurred

What protections are available to the notifier?

A reporter who makes a notification in good faith is not liable civilly, criminally, in defamation or under an administrative process for giving the information

What are the penalties for failing to report?

Individuals may be subject to health, conduct or performance action; employers may be subject to a report to the Minister for Health, a health complaints entity, licensing authority and/or other appropriate entity; education providers may be publicly named by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA)

2 Statutory grounds for notification and types of concerns at issue (n = 811)*

|

Statutory ground and type of concern

|

No. (%)

|

Example of alleged behaviour

|

|

|

Departure from standards

|

501 (62%)

|

|

|

Clinical care

|

336 (41%)

|

An optometrist failed to refer a child with constant esotropia to an ophthalmologist for 2 years, resulting in permanent visual impairment

|

|

Professional conduct

|

107 (13%)

|

A director of nursing engaged in bullying and intimidation, including rude and abusive outbursts towards nurses

|

|

Breach of scope or conditions

|

50 (6%)

|

An occupational therapist with conditional registration did not comply with a requirement that she work under supervision

|

|

Impairment

|

140 (17%)

|

|

|

Mental health

|

75 (9%)

|

A nurse with a history of bipolar disorder began to behave erratically and engaged in loud confrontations with patients

|

|

Cognitive or physical health

|

31 (4%)

|

A midwife suffered a head injury in a car accident and subsequently experienced cognitive deficits, including difficulty with maths calculations

|

|

Substance misuse

|

25 (3%)

|

An anaesthetist self-prescribed medication for anxiety and insomnia and developed a benzodiazepine dependency

|

|

Intoxication

|

103 (13%)

|

|

|

Drugs

|

61 (8%)

|

A nurse working in a hospital had an altered level of consciousness; empty morphine ampoules and syringes were found in her pocket

|

|

Alcohol

|

42 (5%)

|

A surgeon was noted to smell of alcohol and to have slow reactions during surgery; a breath alcohol test was used to confirm that he was intoxicated

|

|

Sexual misconduct

|

67 (8%)

|

|

|

Sexual relationship between practitioner and patient

|

31 (4%)

|

A psychologist began a personal relationship with her patient after the breakdown of his marriage and asked him to move in with her

|

|

Sexual contact or offence

|

28 (3%)

|

A male nurse in an aged care facility sexually assaulted an elderly female patient who was immobile after a stroke

|

|

Sexual comments or gestures

|

8 (1%)

|

A pharmacist asked a patient to lunch and when she refused he posted sexual comments and pornographic images on her Facebook page

|

|

|

* Statutory grounds were unknown for eight cases. Type of concern was missing for a further eight reports relating to departure from standards and nine relating to impairment.

|

3 Characteristics of notifiers and respondents*

| |

Number (%)

|

|

Characteristic

|

Notifiers

|

Respondents

|

|

|

Profession

|

n = 754

|

n = 816

|

|

Nurse and/or midwife

|

387 (51%)

|

482 (59%)

|

|

Medical practitioner

|

220 (29%)

|

216 (26%)

|

|

Psychologist

|

38 (5%)

|

48 (6%)

|

|

Pharmacist

|

29 (4%)

|

33 (4%)

|

|

Dentist

|

7 (1%)

|

15 (2%)

|

|

Other health practitioner

|

16 (2%)

|

22 (3%)

|

|

Non-health practitioner

|

57 (8%)

|

—

|

|

Age

|

n = 750

|

n = 750

|

|

< 25 years

|

4 (1%)

|

16 (2%)

|

|

25 to 34 years

|

69 (9%)

|

111 (15%)

|

|

35 to 44 years

|

159 (21%)

|

204 (27%)

|

|

45 to 54 years

|

281 (37%)

|

227 (30%)

|

|

55 to 64 years

|

219 (29%)

|

145 (19%)

|

|

≥ 65 years

|

18 (2%)

|

47 (6%)

|

|

Sex

|

n = 791

|

n = 816

|

|

Female

|

498 (63%)

|

460 (56%)

|

|

Male

|

293 (37%)

|

356 (44%)

|

|

Relationship to respondent

|

n = 731

|

—

|

|

Fellow health practitioner

|

335 (46%)

|

—

|

|

Employer

|

333 (46%)

|

—

|

|

Treating practitioner

|

58 (8%)

|

—

|

|

Education provider

|

5 (1%)

|

—

|

|

Practice location

|

—

|

n = 809

|

|

Major cities

|

—

|

535 (66%)

|

|

Inner or outer regional

|

—

|

229 (28%)

|

|

Remote or very remote

|

—

|

45 (6%)

|

|

Jurisdiction of practice

|

|

n = 819

|

|

Queensland

|

—

|

321 (39%)

|

|

South Australia

|

—

|

184 (22%)

|

|

Victoria

|

—

|

150 (18%)

|

|

Tasmania

|

—

|

25 (3%)

|

|

Western Australia

|

—

|

97 (12%)

|

|

Northern Territory

|

—

|

11 (1%)

|

|

Australian Capital Territory

|

—

|

31 (4%)

|

|

|

* Differences in n values are because of missing data.

|

4 Frequency of notifications, by profession of notifiers and respondents (n = 697)*

5 Incidence of notifications per 10 000 registered practitioners per year, by characteristics of respondents*

more_vert

more_vert