Equal treatment for equal need is not enough — positive discrimination for disadvantaged groups is also required

With the “reform” of Medicare on the political agenda, it is timely to reflect on the objectives of fairness and equity that are key goals of our national health scheme. These objectives include both “horizontal equity”, or equal treatment for equal need, and “vertical equity”, which involves appropriately different treatment for those with different needs.

The goal of horizontal equity was made explicit by Neal Blewett, then minister for health, in his second reading speech of the Health Legislation Amendment Bill 1983. He stated that a goal of Medicare was “to produce a simple, fair, affordable insurance system that provides basic health cover to all Australians”.1

The goal of vertical equity is implicit in the more recent government policy of Closing the Gap — improving health outcomes for Indigenous Australians relative to the general population.2 The objective of this policy is to eliminate the difference in life expectancy between the two groups within a generation (by 2031) and to halve the excess mortality for Indigenous children under 5 years of age by 2018.2

Disadvantaged populations and vertical equity in health care in Australia

Indigenous Australians are only one of the marginalised populations in Australia. Others include the chronically sick, older people, people from non-English-speaking backgrounds, refugees, those on low incomes, the mentally ill and the homeless. Several policies already exist that seek to improve vertical equity for these groups. They include the use of means-tested safety nets and health care concession cards for people on low incomes, the funding of specific workforces to treat conditions associated with disadvantage (eg, drug and alcohol workers), and the availability of services and programs for particular needy groups, such as dental care for children or case coordination for those with chronic illness. These examples illustrate policies that achieve appropriately different treatment for people with different needs.

Importantly, the Australian Government also has agreements with the states and territories to fund hospital and other health care programs that target particular needs. For example, all states and territories operate patient assisted travel schemes for geographically isolated patients. These schemes provide assistance with travel, escort and accommodation expenses when patients have to travel over 100 km to access specialised health care.3 Several of these policies and programs to improve vertical equity are under threat from the proposed 2014 Budget cutbacks.

Within Medicare, the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) both achieve horizontal equity through their universality, but there are also examples of their use to achieve vertical equity. These include the prioritisation of people with more serious diseases — the so-called “rule of rescue”4 — and a few services determined on the basis of age, such as the MBS Healthy Kids Check for the early detection of lifestyle risk factors, and several physical health services provided by general practitioners and practice nurses that are available for 4-year-olds.5

However, Medicare has not been used explicitly to prioritise those with greater need due to social characteristics such as class, disadvantage or ethnicity, as routinely occurs in the United Kingdom’s National Health Service.6 There are a few exceptions: the MBS and PBS item numbers for Indigenous health workers, and specific subsidies for the treatment of otitis media, fungal infections, alcoholism, smoking and worms — conditions that are overrepresented in Indigenous Australians and people on lower incomes.7 There are lower copayments for Indigenous Australians for several MBS and PBS services and products. For example, the Closing the Gap — PBS Co-payment Measure results in lower or no copayments for PBS-listed medicines for Indigenous Australians who are at risk of, or who have, chronic disease.8 While removing a few barriers to access, such examples are rare.

Medicare does not have an overarching evidence-based decision framework for achieving vertical equity. Doubts remain regarding the extent to which our health care system, and particularly those parts controlled by explicit regulation (the MBS and PBS), is equipped and prepared to make policy decisions to achieve vertical equity; that is, decisions requiring positive discrimination.

The reluctance to pursue vertical equity is, in part, attributable to perceived difficulties with operational methods and public acceptance. Operationally, there could be a concern that such policies would create a precedence for decisions that may lead to future difficulty in “drawing the line”, or a fear of “opening the flood gates”, or being vulnerable to litigation. There may also be a perception that the public or taxpayers would not accept policy decisions that positively discriminate on the basis of social characteristics or disadvantage.

Research into equitable allocation of the health budget

Fortunately, research is available to help with operational decision rules, and there is a strong argument for basing equity objectives on social preferences in a democracy such as Australia. Existing research shows that the general public has clear views about fairness and equity between different groups in society and is capable of articulating preferences that may be used for allocating unequal resources between those with unequal health needs.9 The research to date has focused on health and personal characteristics. For example, people indicate that they are willing for society to pay more for the health of children, those with serious illness, those who were not responsible for their own condition and those with minimal other treatment options.9–11 In the UK, one study of disadvantage by social class found that an incremental increase in life expectancy for the lowest social class was weighted about seven times higher than an equivalent gain for the highest social class by members of the general population.12

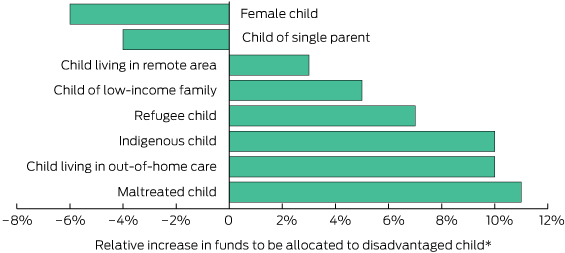

In our own research conducted in 2011, we used relative social willingness-to-pay methods13 and a postal questionnaire to survey the Australian public, randomly approached from a database of general public adults willing to participate in research (Dalziel K, Segal L. The structure of Australia’s health funding systems: who is missing out and how does it align with social preferences? 9th World Congress on Health Economics; 2013 Jul 7–10; Sydney, Australia). Ninety out of 429 people responded (21% response rate). Overall, our respondents were slightly younger, more likely to be single and more educated than the Australian population. In the survey, participants had a hypothetical $40 000 to allocate to a child with asthma to improve either the quality or length of life. Participants were then presented with scenarios in which they were asked to make similar decisions when the child with asthma also had a social disadvantage. The survey results indicated a willingness to increase the budget for children in some socially disadvantaged groups, such as Indigenous Australians, refugees, low-income earners and those in remote locations (Box). The apparent negative allocation preferences for girls and children of single parents are thought to represent an overcorrection made by respondents who did not wish to indicate preferential budget allocation on either basis.

These findings suggest that decisionmaker fears that positive discrimination would be unacceptable to the Australian population may be unfounded, and provide a starting point for quantifying the budgetary implications of seeking vertical equity in the health sector.

The need for evidence-based change

When change to health care structure and funding is being considered, it is important to ensure that new policies do not have a disproportionate effect on low-income and vulnerable Australians.14 The climate of change, however, also provides an opportunity to strengthen Medicare’s commitment to equity objectives in other ways — in particular, by targeting barriers to health care for groups identified as having special needs.15 A proactive approach to such problems should be firmly rooted in research to maximise the effectiveness and consistency of any changes.

Australia’s health system and the health of all Australians will benefit from evidence-based mechanisms to allocate unequal resources to those with unequal health. This is particularly urgent for groups such as Indigenous Australians, whose health outcomes lag well behind those of others,16 but it is also true for other groups. Their needs and the appropriate response to them require further research of the sort described here.

Survey results showing the public’s willingness to allocate additional hypothetical health care funds to Australian children with asthma if they also have a social disadvantage*

* The percentages indicate the relative increase in funds the public would be willing to allocate to a child with asthma in each disadvantaged group, relative to an average Australian child with asthma (Dalziel K, Segal L. The structure of Australia’s health funding systems: who is missing out and how does it align with social preferences? 9th World Congress on Health Economics; 2013 Jul 7–10; Sydney, Australia).

more_vert

more_vert