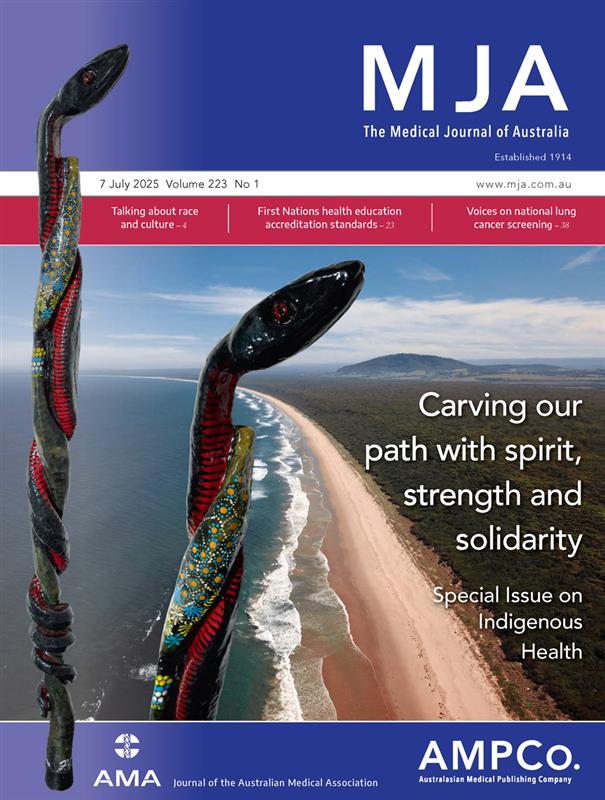

The MJA has published its second Special Issue on Indigenous Health to coincide with the 2025 NAIDOC week.

The issue is called “Carving our path with spirit, strength and solidarity”. And like last year’s Issue, it’s edited by a team of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Guest Editors.

The authors of the articles in this issue have been guided by the Guest Editors through the editorial and publication process. The MJA’s Editor-in-Chief Virginia Barbour said the Journal has a special place in being able to publish these articles and address the Journal’s historical power imbalances.

“At the MJA, we understand the privilege that it is to publish articles from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers,” Ms Barbour said.

“We also understand that a journal like the MJA has a duty to acknowledge and address the imbalance of power that has led, in the past, to publication in the MJA being a hard and uncomfortable experience for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander authors,” she said.

One of the Guest Editors and authors is Biripi man Associate Professor Paul Saunders. He is the Associate Professor and Academic Lead for Indigenous Health in the Graduate School of Medicine at the University of Wollongong.

“I feel really honoured to be involved in this, actually. It’s a big step forward, particularly where the MJA has come from in its established roots on the Australian continent and the role of medical journals in Australia in perpetuating stereotypes and inferiority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples through things like phrenology, eugenics,” Associate Professor Saunders said.

“It says a lot about the commitment to reconciliation and self-determination from an MJA perspective for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population,” he said.

“It’s extremely important this Special Issue, and it’s more than just an issue; it’s quite symbolic in terms of allowing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to control the medical space,” Associate Professor Saunders said.

“And, particularly, given it’s a space that’s very westernised, a space that’s very biomedically centred and focused, to allow Indigenous knowledges to permeate that and have an equal platform is extremely important for realising that there’s more than one way to do things, there’s more than one way to look at health and medicine,” he said.

The perspective in this MJA Special Issue Fulfilling First Nations health, cultural safety and equity accreditation standards in primary medical education: reflections from a First Nations desktop review team was co-authored by Associate Professor Saunders.

The perspective’s authors have been working with the Australian Medical Council in a review of its Standards for assessment and accreditation of primary medical programs. Its new standards include an Indigenous voice that can be heard throughout medical schools.

“And a result of allowing Indigenous peoples in, not just in but to control this space, they’ve revolutionised their standards, their standards for primary medical education providers has transformed immensely and that process is now underway for specialist medical colleges, with plans to then focus on the pre-vocational space, that space between primary medical education and specialty training,” Associate Professor Saunders said.

“So the standards look completely different now, and what it has done is allow that Indigenous voice to permeate medical schools,” he said.

Cultural humility

A bridge between non-Indigenous and Indigenous peoples starts with, first of all, recognising that there is more than one way of seeing the world, and expertise can be both relative and subjective.

“There needs to be an element of cultural humility that includes an understanding that you’re not expert, you don’t know everything, and that can be quite difficult, I think, for medical students or medical practitioners because they’re situated as experts and they often take that label and apply it across their multiple roles within their life beyond that of the medical practitioner or the medical student,” Associate Professor Saunders said.

Challenging that viewpoint requires vulnerability to be open to new perspectives.

“So allowing medical students or encouraging medical practitioners to be vulnerable in that respect is quite important because that then opens the door for them to learn more, because if you’re an expert then you don’t feel you need to learn more, but if you challenge that label, then you are open to further learning, and this is a constant lifelong learning journey,” he said.

Learning that challenges the dominant narrative should start at an early age, in primary school, so it becomes the norm, Associate Professor Saunders said.

Truth telling and self-reflection

Being open to new learning and understanding about Indigenous peoples and the position of non-Indigenous knowledge requires truth telling and self-reflection.

“It involves understanding your positionality in this country, what privileges you hold, ways in which you understand knowledge and ways in which you validate and privilege knowledge,” Associate Professor Saunders said.

“We talk a lot about self-reflection … true self-reflection with an aim to develop self-reflexivity is really about sitting there questioning everything that you know and everything that you do and how others may perceive things differently and how others may do things differently,” he said.

“Just because someone does something differently it doesn’t mean that your way of doing it is better, and I really think that this is the mindset that we really need to tap into because there’s an understanding within the western world that western knowledges are superior and that western knowledges have advanced the contemporary society that we live in,” Associate Professor Saunders said.

“And while that certainly may be true, there’s also Indigenous knowledges and other knowledges that have contributed to that as well,” he said.

“And so, it’s finding validity across multiple perspectives or what we refer to as ‘epistemic pluralism’,” Associate Professor Saunders said.

Deans of medical schools and non-Indigenous faculties are being encouraged to read the guidelines and to reach out to Indigenous communities for help in understanding them.

“Engaging with communities will help with a reciprocal relationship with non-Indigenous institutions,” he said.

Read the Special Issue of the Medical Journal of Australia.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

more_vert

more_vert

Many non-indigenous persons want to reach out to First Nations peoples because they really care. Unfortunately, many are pushed back due to mistrust. Their care and concern are not seen as genuine. They are seen as intruders. No doubt there are valid reasons why non-Indigenous Australians are excluded, reasons which they need to understand, and for that matter, need to overcome. I this where the problem lies? Is it so much the fact that non-Indigenous Australians need to engage appropriately with First Nations peoples or is it the reality that they are not being allowed to do so? Culturally appropriate care? Fine. Well and good. However, you cannot treat a bacterial infection without an antibiotic. That said, understanding is required as to why the medicine has to be applied and what will be, hopefully, the outcome. Trust and understanding has to be adapted by both sides. And, of course, what work with one mob may not work with another. Why is this the case?