Digital mental health services play an important role in future health service design. However, if GPs are to prescribe them, we need more evidence of their accessibility and efficacy.

In a recent press release, the Health Minister Mark Butler claimed that new digital services are the first step towards a better, fairer mental health system. The assertion that “help is just a click away” is attractive, but not necessarily accurate.

To use digital mental health services, consumers need the resources to access and understand them. Many digital mental health services require a high degree of literacy in English, technology and health to interpret and follow the content. In this systematic review of barriers to adoption of digital mental health services, the authors cite a series of structural, individual and professional barriers to the use of digital services. Consumers may not have access to the technology required, they may lack cognitive resources to make sense of complex concepts when they are unwell, they may find the resources inappropriate to their own cultural context, or they simply may not like them or find them helpful. “Digital poverty” is a form of exclusion, restricting access to resources others take for granted, including health care. People who lack the skills, resources or capacity to engage with digital health resources may well be the people with the greatest mental health needs.

Help may be “just a click away” for some, but is clearly not available to all.

Are digital mental health services effective?

The evidence for digital mental health services is often presented as overwhelmingly positive. One systematic review panel explored studies around mobile phone apps and concluded “we failed to find convincing evidence in support of any mobile phone-based intervention on any outcome”. There are a series of challenges in implementing the findings of these studies into clinical care, particularly in General Practice. These include methodological limitations, conflicts of interest and limited reporting of negative outcomes. However, the most important limitation of these studies is the representativeness of the population sample. The diversity of the study samples is rarely reported, but is likely to be narrower than the communities in which they will be implemented.

Drop-out rates with smartphone apps and other digital tools are high, so it is difficult to rely on the findings.

The evidence behind the National Digital Mental Health Framework

The National Digital Mental Health Framework claims that “Digital mental health services can improve access barriers for traditionally underserved cohorts by overcoming geographical and socio-economic barriers. They also provide consumers with the ability to exercise greater choice and control over when and where treatment will take place, presenting as a valuable option for consumers who are reluctant to use face-to-face services.” It supports this claim with only one reference, a surprisingly outdated paper looking at evidence from 1998 to 2009.

Later, the Framework references the National Safety and Quality Digital Mental Health Standards (2020) by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. The Commission also references only one paper to support their claim that “there is growing evidence regarding the important role digital mental health services can play in the delivery of services to consumers, carers and families.” The paper cited is a more modern one (2016), but one with significant flaws. To illustrate the challenges of interpreting the digital mental health evidence, I have summarised the findings of the cited paper below.

The MindSpot study: an evaluation

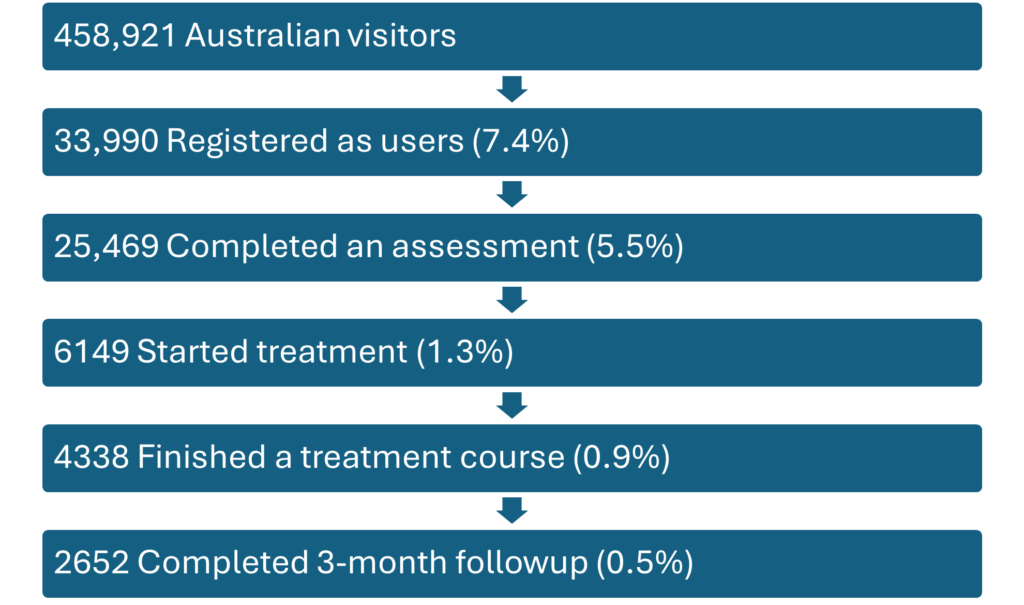

The paper examined the MindSpot Clinic (an online digital mental health service). Here’s the attrition of their convenience sample of people visiting their website in the 30 months of the study. One interesting observation in this study is that 76% of participants who completed assessment were thought to be unsuitable for the MindSpot intervention.

The team describes that “large clinical effects were found from assessment to follow-up on all outcome measures.” On this basis, they claim that their service “has considerable value as a complement to existing services, and is proving particularly important for improving access for people not using existing services.”

The 99.8% of people who visited the site and did not engage remain unresearched. We do not know whether they were harmed or whether they recovered more quickly or more effectively than the cohort who completed the study. Using a paper like this to claim that digital mental health services have “considerable value as a complement to existing services, and is proving particularly important for improving access for people not using existing services” seems an inflation of their research outcomes.

Next steps

It is clear that digital mental health services play an important role in future health service design. However, if GPs are to prescribe them, we need to have more than persuasive tactics at our disposal.

The evidence-based medicine triad [AH3] outlines the three conditions under which GPs should prescribe an intervention:

- We need sufficient research evidence.

- We need to form a professional opinion that the intervention is appropriate in a particular clinical context.

- The patient needs to decide that they are willing to accept this form of care.

In the case of digital mental health interventions, I need three conditions to overcome my reluctance to prescribe. I need independent research, and Therapeutic Goods Administration endorsement through application of an appropriate digital mental health standard. I need to know enough about the demographics of the cohort studied to be able to decide whether the research applies to my patient and their situation, and the patient needs to decide that the intervention is right for them. Without this fundamental information, we cannot form a valid professional opinion about the appropriate use of any app, helpline, artificial intelligence program or digital course.

Early in my career, I was trained to analyse the science beneath any drug or device, and avoid the influence of pharmaceutical representatives with vested interests persuading me to prescribe their intervention of choice. I am unlikely to change my professional values and acquiesce to the marketing of new interventions now, no matter how hard funders and managers attempt to drive me to adopt these models of care. I am satisfied that this is the unavoidable consequence of exercising appropriate clinical judgement.

It is my duty to form my own professional judgements and my patients rely on my professional integrity to reject marketing pressure. If anyone misinterprets GP conduct as reluctance, rather than conscientiousness, they are underestimating our commitment to good practice.

We have seen marketing behaviour before with a variety of drugs and devices. We have not forgotten the marketing behind “non-addictive” opiates, or the damage caused by regulated medical devices. We are understandably wary when claims of efficacy outstrip evidence. Our patients deserve better.

Dr Louise Stone is a Canberra GP with clinical, research, teaching and policy expertise in mental health. She is an associate professor in the social foundations of medicine group, Australian National University Medical School.

Read part 1: Are GPs ‘reluctant’ to prescribe digital mental health services?

Read Part 2: Are digital mental health services cost-effective and safe?

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

I find it interesting that Louise is holding digital mental health tools and programs to an exceptionally high bar. There is also limited and mixed evidence to support effectiveness and fidelity of face to face psychological treatment as it is *actually* delivered in real world practice under the Medicare better access to care scheme. If Louise were to apply her referral criteria across the board, I’m sure there would be few treatments and services she would refer to.

As the Executive Director of the MindSpot Clinic referred to in this piece, I was shocked by Dr Stone’s description of the findings of our article (Titov et al., ANZJP, 2016).

I strongly support robust debate about quality, but Dr Stone has either misread this publication, or has intentionally misrepresented it. Dr Stone begins by implying that all of the 459,000 visitors to the MindSpot website should have received treatment – this expectation that all visitors to a website will register as users is unrealistic and is a disrespectful attempt to discredit MindSpot.

Dr Stone correctly notes that almost 34,000 people registered as patients of MindSpot, but fails to report that more than half said they were primarily seeking a confidential psychological assessment and information about their local services. Digital psychology services such as MindSpot assist people to understand their symptoms and navigate their treatment options; this is a valuable service for people who cannot or will not access traditional services.

It is important distinguish between clinician-guided digital psychology services such as MindSpot and information sites or apps. We have published more than 100 peer-reviewed studies related to our work including a large number of randomised controlled trials – a simple search of Google Scholar would have shown this.

We nevertheless commend Dr Stone for her questions about safety and quality. Internationally, this is a topical question, and countries such as Sweden have developed a national register of outcomes from digital mental health services which benchmarks their outcomes. The developer of that register has recently advised that the Swedish model will be extended to include results from other mental health services including psychologists and possibly GPs and psychiatrists. We hope that readers of InSight would support an Australian version of such a register.

MindSpot is not a panacea and serves as one component in our contemporary mental health system. We work closely and collaboratively with a large number of GPs and other service providers in the best interests of our patients and we welcome respectful discussions and enquiries.

I’m a GP working for the e-Mental Health in Practice Project (eMHPrac) helping GPs and allied mental health professionals learn about Australian made evidence-based online mental health resources and how to use them. Many of the people I speak to have had good experiences using these resources.

I’m wondering if everybody is aware that there is an accreditation process for online mental health resources run by the Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in Health Care? The accreditation process covers the safety and efficacy of the programs and resources, the security of data and the research to support the efficacy of those programs. (Here is a link to the relevant standards https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/national-safety-and-quality-digital-mental-health-standards). If GPs are concerned about any of those things they may prefer to stick to programs that have the imprimatur of the Commission.

If practitioners are interested in looking at the research for themselves there is a database of research on the eMental Health in practice website that includes the papers Louise refers to. (Here is a link to the evidence page of that site https://www.emhprac.org.au/evidence/ ) As always research can be interpreted differently by different readers. Looking at it for yourself might provide you with a different perspective to Louise’s.

Finally, I totally agree with Louise about digital resources are not being good for everyone. But for the people who find them helpful they can go a long way to fill the yawning gap between face-to-face care and no care at all. Ignoring these resources is just throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Being a long term rural GP, the strong opinion of most of my patients re digital mental health platforms is that their needs are neither being seen nor addressed, and that they are being fobbed off with a “cheap” option because nobody wants to travel out to actually see them in person. Patients of all ages, with a full range of diagnoses. I am concerned that so much is being poured into creating “yet another bloody app” when there are such huge gaps in actual personal services, even by video consultation. And where GPs are not being resourced and woeful patient rebates actively discourage comprehensive mental health management via the GP whether rural or urban. (and no, the large BB rebate incentive doesn’t apply to item 2713 either) . How many government $$ exactly have been spent on an app where 0.9% completed the on-line treatment course? Those $$ might have been better directed into resourcing on-ground primary care providers who might then be able to spend the time assisting these patients face to face. There is quite a range of existing computer programs and apps, some of which the patients already use for specific items like self calming or mindfulness in conjunction with their GP and psychologist/ mental health nurse appointments. I feel that either we have reinvented the wheel here, or we’re spending a load of money on something that is there to treat our need to feel something has been done (and which can be trotted out as a shiny new vote winning item) .

“Help” does not mean either it is the total solution or that it is for everyone. We need a suits of options and digital services are part of that suite. I repeat, not the total solution and not for everyone.

This is an excellent piece that expresses my views and practice perfectly! I would add that there is increasing evidence that time spent online by young people has a strong correlation with mental illness. Suggesting a treatment of more time spent online is counter-intuitive. Commonsense would suggest that human contact is the key, particularly for those who have reached out to the human GP.