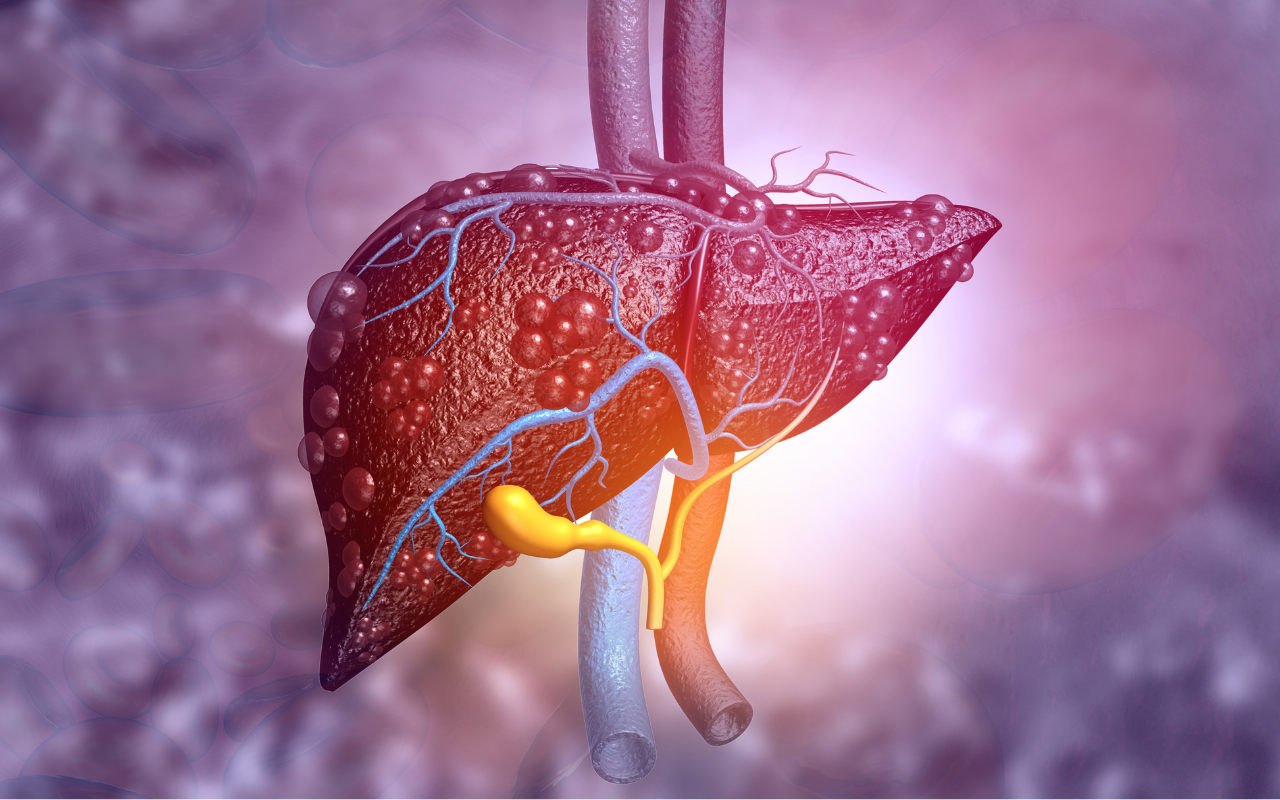

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease can cause severe morbidity and affects around 5 million Australians, but is typically asymptomatic until the late stages of the disease.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is rising in Australia, with a disease burden that is likely to affect 7 million people by 2030. NAFLD is also known as metabolic (dysfunction) associated fatty liver disease.

Despite this, hepatologists do not believe there is enough awareness of the condition.

NAFLD in Australia

Research published in the Medical Journal of Australia examined the incidence of decompensated cirrhosis and associated risk factors in people hospitalised with NAFLD or non- alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) with or without cirrhosis.

They found that more than a third of people with NAFLD-related cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus experienced cirrhosis complications within ten years.

“One in five people with diabetes mellitus have clinically significant hepatic fibrosis,” the authors wrote.

“The greater risk of progression to cirrhosis decompensation in people with both NAFLD and diabetes mellitus has important consequences for the future burden of NAFLD-related disease in Australia”.

Co-author Professor Patricia Valery said the condition is of particular concern because of the steep rise in obesity.

“We are seeing an increasing number of people with NAFLD, and many are in their 20s and 30s,” she told InSight+.

In other comparable countries, NAFLD has become one of the most common chronic liver diseases, affecting 25–45% of adults in the general population and up to 70–90% of people with obesity or type 2 diabetes.

“We conducted this study because data on the prevalence of this problem in Australian patients was lacking and we wanted to measure the size of the problem,” she said.

Type 2 diabetes, obesity and components of the metabolic syndrome are risk factors for the progression of NAFLD to later stages of liver disease. Diabetes affects one in 20 Australians, and 15–20% of people with diabetes have clinically significant fibrosis.

“The key message from this study is the increased risk of progression to cirrhosis, liver cancer and liver failure in people with NAFLD, especially if they also have diabetes,” she said.

Working out who is at risk

Professor Leon Adams from the University of Western Australia told InSight+ that the challenge for primary care doctors is that they have so many patients with NAFLD.

“Trying to identify the ones that will develop significant liver morbidity is really challenging,” Professor Adams said.

“Our standard liver tests and imaging are not sensitive and so we need to integrate accurate non-invasive fibrosis tests into standard clinical practice in primary care to identify those at risk.”

One barrier is trying to make sure those assessment tools are accessible to GPs.

“Unfortunately, one of the main technologies we have to assess liver fibrosis at the moment, called elastography, isn’t Medicare-rebated,” he said. “So that’s the major barrier for patients to access it.”

Current treatments

The other area of research is therapeutics for when a patient gets diagnosed.

According to Professor Adams, there is plenty of promise.

“There’s a lot of research, a lot of clinical trials that have been done,” Professor Adams said.

Several which have reached late phase development. Hopefully, within the next few years, we’ll have some good evidence for effective drugs in this area.”

According to Professor Valery, lifestyle changes and management of metabolic conditions are crucial.

“While to date there is no approved medication to treat NAFLD, new diabetes medications used in patients with NAFLD and diabetes are showing encouraging results in reducing the progression of NAFLD,” Professor Valery said.

“What stands out in this research is the rate at which progression occurs, especially in people with diabetes and cirrhosis, where one-third developed liver-related complications.

“Improving early recognition of NAFLD, particularly in those most at risk, such as people with type 2 diabetes (as recommended by forthcoming national guidelines) is therefore essential.”

Read the research published in the Medical Journal of Australia

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

more_vert

more_vert

NAFLD is easily reversed by making a simple dietary change.

Attended a lecture recently by Prof Alan Wigg (Prof of hepatology/Liver Transplant Unit FMC Adelaide) who confirmed that NAFLD is now referred to as MAFLD ie “a specific diagnosis” due to obesity, diabetes or metabolic syndrome that can occur with Alcohol FLD or any of the other causes of chronic liver dis.

Much more sensible that the broad non specific term NAFLD which I understand is obsolete.

Also, I can order liver elastography at my local radiologist (with specific indications) with a medicare rebate !