In her previous articles for InSight+, Dr Sarah White has written about clinical communication, drawing on her and others’ experiences to illustrate research evidence on the science on health care interactions. In this article, she interviews Dr Rhiannon Parker from UNSW Sydney’s Centre for Social Impact, taking on the role of patient, and drawing on Dr Parker’s expertise around gender and health and systemic sexism in health care to explain what is going on.

SARAH WHITE (SW): Between babies number 2 and 3, I started experiencing very painful and heavy periods. From the onset of these severe symptoms to a diagnosis of adenomyosis, I waited about 4 months, primarily because it took me a couple of months to bring the problem to my GP.

This makes me feel lucky – lucky that my GP took me seriously and was able to provide a tentative diagnosis that was able to be confirmed by my gynaecologist, who I was able to see soon after being referred.

This felt lucky, as adenomyosis, like endometriosis, on average takes longer to be diagnosed. Across different conditions, is there a gendered difference in diagnostic or treatment delay? If so, why?

RHIANNON PARKER (RP): Throughout history, women, intersex, non-binary and transgender people have, and continue to be, understudied, underdiagnosed, undertreated and undermanaged in medicine (here and here).

While we are starting to see an increase in research that includes women and sex/gender diverse people, the repercussions of their historical under-representation in research and education are incredibly difficult to overcome.

For example, about 30 years’ worth of research has consistently shown evidence of the differential treatment and diagnosis of men and women for cardiovascular disease (CVD; here and here). But research on women and CVD continues to be underrepresented and underfunded. As a result, women’s CVD symptoms are often missed or dismissed by both patients and health care professionals who don’t recognise the unique warning signs. This happens across a range of conditions including autism and [attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)].

Research, diagnosis, and treatment for gynaecological and obstetric conditions have also been inadequate. For example, one of the top undiagnosed conditions in women is endometriosis. After the onset of symptoms, a diagnosis for endometriosis can disturbingly take 4–11 years.

It’s important to note that these issues are exacerbated when looking at the intersection of gender and marginalised and minority populations. Women who aren’t white, young, thin, able-bodied, cisgendered and wealthy often encounter discrimination, stigma and misdiagnoses that result in worse diagnostic and treatment delays (here and here).

SW: With a few years in between and different strategies of management, I find myself again having my life negatively impacted by adenomyosis. Now my feelings of being lucky have turned to feelings of being privileged as well.

While I am lucky that my gynaecologist prefers less invasive treatments, I am privileged to have access to and be able to afford the private system that makes relatively swift diagnosis and treatment possible. To provide an accurate diagnosis and, quite literally, a clearer picture of my adenomyosis, I was required to have [a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan]. Unfortunately, there is only one MRI item number specifically for gynaecological health: a once-in-a-lifetime claim for cervical cancer imaging, meaning I paid entirely out of pocket.

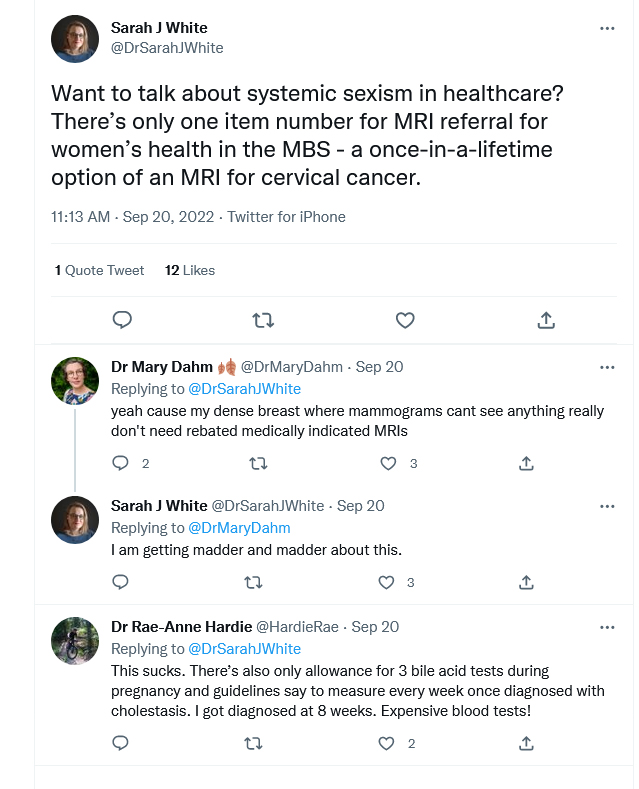

I shared my frustration about this on Twitter, which revealed other diagnostic tests and scans where there are mismatches between clinical guidance and the [Medicare Benefits Schedule]. These, too, are detrimental to the health of women and sex and gender diverse people.

If there is no clinical reason to not include such item numbers, is there one associated with gender? Where does this stem from?

RP: The pervasive exclusion and stereotyping of women in medicine has been reflected in our health care policies. In Australia, only two out of the top ten medical funding agencies have policies requiring the collection, analysis and reporting of sex‐ and gender‐specific health data. Policy that specifically aims to reduce gender inequality in health care is limited. This likely means that methods to diagnose and treat women, intersex, non-binary and transgender people rely on the workarounds developed by frontline workers.

SW: Access to health care should not be based on luck and privilege. Given that about one in five people have adenomyosis and how severely it impacts their lives, access to appropriate care shouldn’t be limited to those who can afford it.

RP: Gender is one of the most significant determinants of health inequalities, especially when coupled with other marginalised identities.

We need policy that directly tackles this issue so that health care workers aren’t relying on band-aid solutions. We need policy that helps women, intersex, non-binary and transgender people thrive.

Dr Sarah J White is a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Social Impact, UNSW Sydney, and an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at Macquarie Medical School. Dr White is the current Australian National Representative for the International Association for Communication in Healthcare and Director of clinical communication consultancy Bedside Manners.

Dr Rhiannon Parker is a Research Fellow at CSI UNSW Sydney. She is a qualitative researcher whose work has focused on the intersections of social justice, health and education. She is interested in exploring and working to improve lived experiences of education, health, illness and care.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert