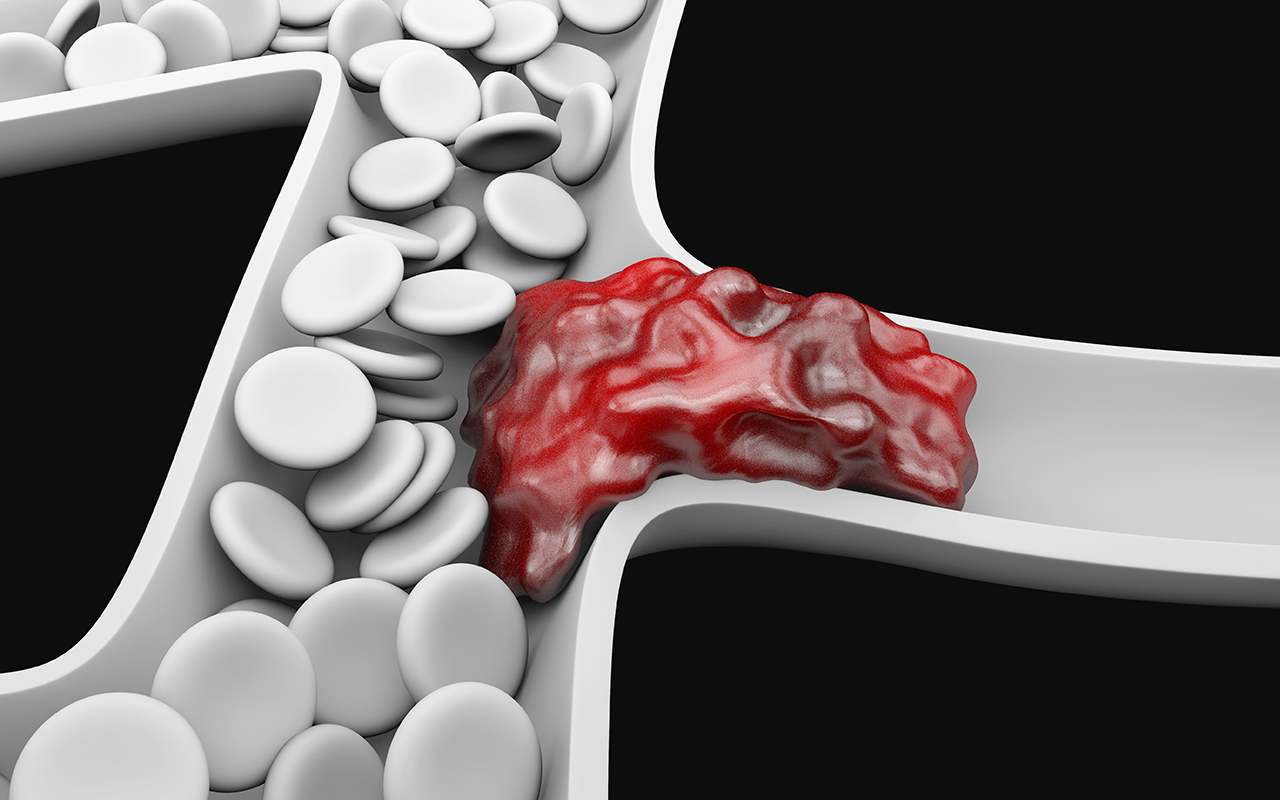

A REVOLUTION in the treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in the past 15 years has prompted the development of the first Australasian guidelines for the diagnosis and management of the condition.

The Thrombosis and Haemostasis Society of Australia and New Zealand (THANZ) have had a summary of the new guidelines published in this week’s MJA. The lifetime risk of VTE, which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is 8%, the experts reported.

In an exclusive InSight+ podcast, lead author Associate Professor Huyen Tran said: “In the last … 15 years, there has been a huge revolution in the treatment of VTE.”

He said the introduction of direct oral anticoagulant therapy (also called new oral anticoagulant therapy or NOAC) had brought significant practical advantages in the treatment of VTE.

“[Therapy] can now be administered orally and much more conveniently,” said Associate Professor Tran, who is head of Alfred Health’s haemostasis and thrombosis unit, and associate professor at Monash University. “Back in the 1980s and 1990s, everyone [with VTE] had to be in hospital for an intravenous infusion of heparin and then we had to cross over to warfarin.”

Haematologist Emeritus Professor Alexander Gallus, of Flinders University, said the introduction of direct oral anticoagulant drugs had, for many patients with VTE, enabled a shift from specialist to general practice care.

“While vein thrombosis used to be treated by [haematologists], it’s now mostly treated by GPs because the newer anticoagulants make that so much more possible,” Professor Gallus, who is not an author on the MJA article, told InSight+.

“It’s not like warfarin, where you have to pay a lot of attention to drug interactions, lifestyle interactions, laboratory controls and dose adjustment; these [drugs] are one-size-fits-all, up to a point, and, therefore, VTE has become very much a community-practice disorder.”

Professor Gallus welcomed the clear diagnostic pathway described in the guidelines, and said evidence-based recommendations on the duration of treatment would help to minimise practice variation in this area.

“We still have uncertainties as to where some of the treatments fit into the story, such as thrombolysis for extensive vein thrombosis, but [the expert committee] has really done a very nice job covering the field.”

The guidelines recommend that the diagnosis of VTE be established with imaging. VTE could be excluded, the experts said, using clinical prediction rules combined with D-dimer testing.

Recommendations for the duration of anticoagulant therapy are dependent on whether the VTE event was provoked (ie, caused by major surgery or trauma, or by a non-surgical transient factor, such as immobilisation due to an acute medical illness or long-haul travel) or unprovoked.

For example, the guidelines recommend that patients who develop a proximal DVT or PE caused by major surgery or trauma that is no longer present should be treated with anticoagulant therapy for 3 months. The guidelines note that the risk of recurrence for a first VTE provoked by major surgery or trauma is 1% at one year after stopping anticoagulation therapy, and 3% at 5 years after stopping therapy.

Speaking on the InSight+ podcast, Associate Professor Tran said for patients with an unprovoked VTE, the risk of recurrence was 8–10% in the first year after ceasing therapy, with a cumulative risk of 30–40% in the following 5 years.

“There is a very strong case for [these patients] to remain on anticoagulation,” Associate Professor Tran said.

For patients who fall in between these two categories – for example, they may have developed a VTE after a 15-minute arthroscopy – Professor Tran said there was clinical “equipoise”.

“We need to have a good discussion with the patient about the pros and cons of stopping versus continuing,” he said. “The benefit now of having these direct oral anticoagulants [is that they’re] much more predictable in their pharmacological properties and the rates of bleeding … there’s a greater tendency for the patients to lean towards staying on extended anticoagulation.”

The experts emphasised the importance of considering occult malignancy in patients presenting with unprovoked VTE. They reported that up to 10% of such patients were diagnosed with cancer in the year after a VTE diagnosis.

Associate Professor Tran noted that 5000 people per year died from PE in Australian hospitals. In October 2018, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care released a clinical standard for the prevention of VTE.

An extended version of the THANZ guidelines can be found at https://www.thanz.org.au/resources/thanz-guidelines

more_vert

more_vert

The indications for treating proximal DVT’s is fairly clear. The current debate is treatment of symptomatic below knee DVT