As pancreas cancer rates rise, Professor Steve Robson reflects on his personal ties to the disease, and his hopes for future screening and treatment.

In January of this year I became the first Australian to undergo a new test for that most feared of diseases – pancreas cancer. I decided to have the test because the most likely reason I will die is pancreas cancer, and that is anything but a good death. This new surveillance test is based on detection of abnormal cell-free DNA (cfDNA). Although these are early days, cfDNA-based tests for pancreas cancer have levels of sensitivity and specificity well over 90% in people at high risk. This compares very favourably with invasive imaging techniques such as transoesophageal ultrasound. I have been using cfDNA tests routinely for more than a decade in pregnancy so feel very comfortable with the technology.

My decision to take the new test falls outside of the excellent and evidence-based guidelines for the early detection of pancreas cancer. What drove my decision-making? Does the decision I took have implications for the way all of us guide our patients? Are there lessons to draw from my experience?

I have good reason to fear this disease. Over two decades pancreas cancer has taken the lives of five uncles and aunts in my father’s generation. It is difficult to describe the impact this series of losses has had on my family – and on me personally.

Although I like to think of myself as a rational clinician-scientist, years of emotional devastation have left my generation – more than 20 cousins in a high-risk cancer family – clinging to the debris of our parents’ suffering like survivors of a shipwreck. Like souls struggling to stay afloat in the oil slicks of a maritime disaster, many of my family members feel like the sharks are circling and will start picking us off at any moment. This fear is one that likely affects hundreds of thousands of other Australians who have witnessed the suffering and loss of relatives to cancer. That is a fear that I want my own children to be free of.

While, overall, the outlook for Australians with a cancer diagnosis has improved over recent decades, the news for pancreas cancer seems to be getting worse. When the first of my father’s generation, my uncle Arthur, was diagnosed with the disease – and succumbed to it only months later – in 2006 there were a total of 2330 deaths from pancreas cancer across Australia. By the year 2023 when Gordon, the last of my uncles to pass away, lost his life, the total number of national deaths had increased by 70% to almost 4000.

Over that same period the rate of pancreas cancer in Australia has increased by almost 40%, taking it from the sixth most common cause of cancer mortality to the third. This change forced the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare to upgrade pancreas cancer from a malignancy that was ‘less common’ to its current status – a ‘common cancer.’ The overall five-year survival for pancreas cancer in Australians has increased from just over 5% in 2006, when the first of my uncles passed on, to 14% by the time of our family’s most recent loss in 2023. That certainly is an improvement, but overall survival for pancreas cancer remains the worst of all malignancies except for mesothelioma. Fewer than 900 Australians are diagnosed with mesothelioma each year.

Since my days as a medical student in Brisbane in the early 1980s, pancreas cancer has been viewed through a lens of deep pessimism by my colleagues. Outside of our profession, the deaths of celebrities such as Patrick Swayze and Aretha Franklin, and heroes for my generation like Midnight Oil drummer Rob Hirst, have done nothing to dispel the sense of nihilism a diagnosis of pancreas cancer brings.

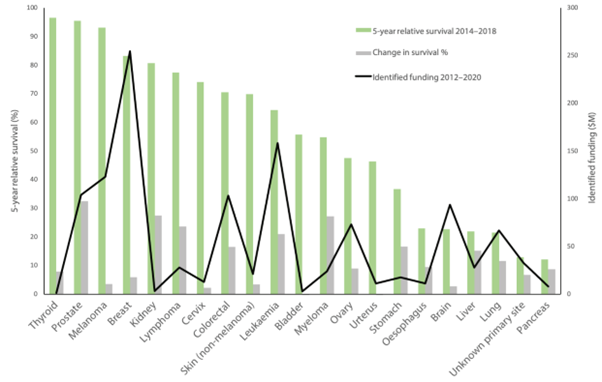

In Australia, at least, this sense of therapeutic nihilism is anything but imaginary. Data from Cancer Australia show that investment in pancreas cancer research and programs in this country has been as dire as the prognosis for the disease itself. (Figure 1)

About 10% of pancreas cancer cases likely are hereditary, but many others occur in people with one or more of a constellation of risks. Some of these risks are difficult or impossible to avoid – such as ethnic background or pancreatitis – but alcohol use, smoking, and being overweight are things we can potentially deal with.

What is abundantly clear is that early detection of pancreas cancer is the key to achieving good outcomes. The obstacle to this is that, in the majority of cases, presentation occurs at a late stage in the disease. In every case of pancreas cancer in my own family, the diagnosis was made when the tumour had spread beyond the pancreas itself. Yet there is good news: recent studies have demonstrated that screening and early detection in people at high risk of pancreas cancer delivers marked improvements in survival.

The test I had – presumably the first of many – is based on cfDNA technology. The same technology that now is so familiar in the form of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) in pregnancy. Indeed, this re-purposing of cfDNA analysis grew from recognition that some false-positive results in pregnancy resulted from otherwise unrecognised malignancy. I now find myself coming full circle – and on the cusp of what I am desperately hoping will be another revolution.

This time, however, I am a participant and patient, not a practitioner. If it is my fate – and that of my family – to develop pancreas cancer I want the diagnosis to be made as early as possible, and to be the beneficiary of the rapid advances in precision oncology. I want the care we receive to be that of the new paradigm – tumour agnostic therapy – that is advancing rapidly. Where flagship programs such as Australia’s Omico are reshaping the way we think about cancer treatment.

The outlook for those souls diagnosed with pancreas cancer is now being transformed. Novel tumour-agnostic treatments that target KRAS mutations, for example, already are delivering very promising results in clinical trials. Work with immunotherapeutic approaches is exciting too, with mRNA-based ‘vaccines’ providing further prognostic improvements in advanced disease.

Indeed, it now is possible to see on the distant horizon the possibility of a ‘cancer vaccine’ that could be used pre-emptively in high-risk individuals to reduce their risk of malignant transformation of cells in the first place. For survivors clinging to the wreckage, as my family are, this feels like seeing the plume of a rescue ship off in the distance.

As a health economist I understand the difficulties society faces in making valid economic assessments of these new precision oncology treatments and tests. Resources are not limitless, and our community must make rational decisions about how to apportion scarce resources for the best health outcomes. At this point I confess that, even though I am both a clinician who manages cancer and an economist, my personal experience as a patient and member of a high-risk cancer family affects my judgement. A lot. Yet I challenge you to show me someone who is not affected by personal biases in some way.

The development, acceptance, and implementation of surveillance guidelines can be a very difficult process. Invariably compromises are made, and recommendations are only as good as the most recent evidence underpinning them. Ultimately, they represent the best efforts of committed people trying to breathe life into words on a page at a moment in time. My decision to sidestep the accepted guidance for people in my situation holds lessons for every one of us. My choice is no more or less valid that the choices made by every other individual in the country.

Every one of us has our own experiences, our own fears, our own wishes, and our own individual circumstances. I am extremely lucky – I can afford this surveillance and have the experience and training to delve into the literature. Many other Australians do not have these advantages, and we are justified in putting our faith in those who develop guidance for us to consider everyone’s best interests in their work. As I navigate the nuance of helping my own patients consider screening pathways in the future, I hope my own experience will make me better at it.

Professor Steve Robson is chief medical officer at Avant Mutual. He is also chair of the National Doctors Health & Wellbeing Leadership Alliance, professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the Australian National University, and a council member of the National Health and Medical Research Council.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

I wonder when insurance companies will start charging more for those with genetic links to disease?

The link you posted to the cfDNA-based test article shows remarkably promising results. When will this be available for anyone to request?

Screening tests are really only effective if they are applied to an ‘at risk’ population.

If the General Population think this is a ‘good thing’ to have then the false positives will become overwelming, and there will people who may be harmed by subsequent medical interventions.

Thank you Steve. Having just diagnosed another patient with metastatic pancreatic cancer I am feeling that all to common sense of despondency. A loved one has an aunt who died of pancreatic cancer and has dysplatic naevus syndrome; a recognised risk of that not only being increased risk of melanoma but G.I cancers especially pancreatic cancers. That some of our colleagues don’t ” believe in” dysplastic naevus syndrome is one thing but the economic argument is moot for those of is who prioritise our health. How does one access this testing?