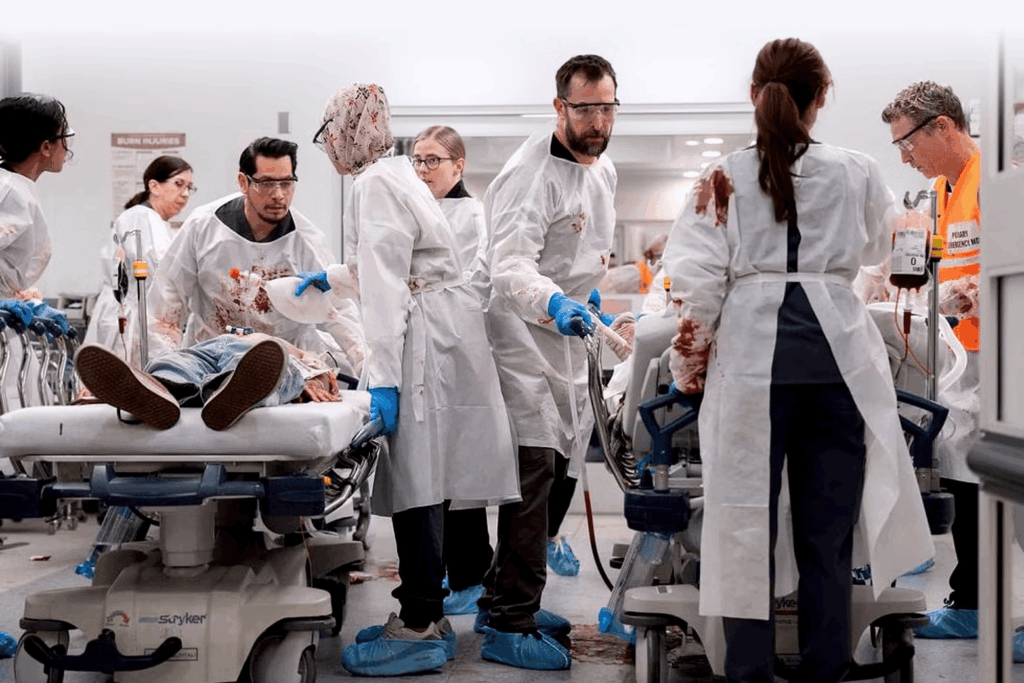

Emergency medicine has been coding since COVID-19 due to overcrowding and understaffing. New television series ‘The Pitt’ – the trauma-informed, adult child of ‘ER’ – is screaming about the state of emergency health care in the United States.

InSight+ asked emergency doctors, including The Pitt’s Australian doctor and a writer, whether a TV series can make a difference.

Dr Mel Herbert is a Professor of Emergency Medicine at the UCLA School of Medicine. He studied medicine in Australia, but has practiced in the US for the last 35 years. He was a writer for the TV show ER.

“We in emergency medicine have been in denial about the stress of the job and the burnout. When I started residency at UCLA, ER docs were burnt out. We were told that it’s because they weren’t trained in emergency medicine.”

“Now we have this great training, and you watch The Pitt and it’s the real deal. But they’re still burnt out. That’s because it’s a stressful job. Patients are dying.”

“And then you have to see the next patient, see the next. You’re fighting a system that doesn’t really give a sh*t about you, because you don’t bring in as much money as elective surgery.”

Dr Herbert said that the creators of The Pitt wanted to make something more realistic, especially in the wake of COVID-19.

“R. Scott Gemmell, the show’s creator, was a writer on ER. During COVID-19, Noah Wiley (who played Dr John Carter on ER and plays Dr Michael Robinavitch on The Pitt) was getting a ton of emails from the ER docs and nurses that he’d gotten to know over the years of ER, saying, “Things are so bad. Could you do a new show showing the terrible things that have happened because of COVID-19 and overcrowding?’”

Wyle and the show’s creators got together to discuss how they could do it realistically.

“‘Let’s do it one shift, real time. Fifteen hours, hour-for-hour, relying on Joe Sachs – a board certified emergency medicine doc with a film degree – to make the medicine as accurate as possible.”

The show has been praised by emergency doctors for its accuracy.

“[The writing team has] a number of ER docs. Seven of us total. It’s the most realistic representation of what happens in modern emergency medicine that there’s ever been. Much more realistic than ER,” he said.

Modern emergency and moral injury

Dr Herbert retired just before COVID-19, but decided he must go back.

“I’ve never seen so many people die.”

“We see people die in the ER all the time, but I’ve never seen so much death. It was a weird experience because you’d be outside the hospital and think, ‘Well, there are no dead bodies on the streets here. It can’t be that bad.’”

“In the ER you’re like, ‘Oh my lord.’ It’s not just 80-year-olds: it’s 30- and 40-year-olds dying.”

Dr Herbert and his wife, a nurse, went to work at a vaccination clinic to help.

“We were living in a real world conspiracy at the same time. First, doctors and nurses were heroes. But then it turned. It was like, “Oh, you’re lying. Ivermectin is the treatment for this.”

“Also, so many nurses left the profession because it was horrible,” he said.

“One of the biggest problems we have now is that the ED is overwhelmed. You can’t bring a patient into a room and do a proper exam without doing this shuffle. And there’s a lot of moral injury.”

Dr Herbert says that moral injury – the guilt, shame, and social alienation of knowing you can’t save everyone, but trying anyway – is a big driver of C-PTSD and PTSD in emergency medicine.

“It’s right on the brink of collapsing the whole time.”

Seeing behind the curtain, and the cape

“There was one scene, where one of the characters is being critical about masks and the doctor finally breaks and says, “OK, so do you want the surgeons in the OR not to wear a mask, because they don’t work?” said Dr Herbert.

“In season one, when Dr Robinavich (Wyle) breaks down, it is one of the most powerful things that’s happened for emergency medicine, and mental health.”

“Here’s our hero, who’s supposed to ride in on the white horse and make everything better. And in comes the horse, and the rider is on the ground, crying, because he can’t take it anymore.”

“That has opened up emergency medicine here in the U.S. to talk about it openly.”

“The Pitt showed that, particularly in the US, sometimes [emergency medicine] is war. You’re in a MASH unit in a mass casualty event, and you are suffering all the PTSD that soldiers and surgeons in war feel.”

“Male ER docs kill themselves at a rate of three times that of the rest of the population. So it’s a profession that is in serious trouble for lots of reasons, and it’s only getting worse.

“Now we’re talking about it.”

Australian emergency

Doctor Belinda Hibble is the Director of Emergency Services at Barwon Health, a large regional mixed emergency department in the southwest of Victoria. Dr Hibble also chairs the Council for Advocacy, Practice and Partnerships at the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM).

“I binge watched the first season [of The Pitt], and was hanging out for the second season,” said Dr Hibble.

“On a good day in emergency medicine, it is such a beautiful place to work. When it hums,” she said.

“Shows like ER – and I remember Chicago Hope and All Saints – often imply a really linear care, and that everything’s urgent, and has a resolution.

“When people present for emergency care, they see themselves in a system. They don’t necessarily have a broader perspective of all of the jigsaw pieces; what we experience.”

“We might have to wait and see and not get that resolution today. And I think some of these TV shows contribute to that [expectation].”

“Real emergency medicine involves managing uncertainty at every level, balancing risk and accepting imperfect outcomes.”

“Most of the work that we do as emergency physicians is quite cognitive, invisible. It’s thinking through how I can improve the care for this person in the limited amount of time and resources.”

“The Pitt resonates with clinicians more because you see realistic emotional fatigue and cognitive load being portrayed.”

“You see the blunting of emotions, and people getting tired, rather than being the heroes of the situation.”

“What the Pitt demonstrates quite well is that interrupted thinking.”

Interesting advantages of the U.S. system

Dr Hibble says that while the Australian system is better, there are some advantages to American EDs.

“How emergency physicians are supported is quite different in the US compared with Australia.”

“In many US contexts, the emergency physicians function as decision makers, and then all of the systems support actioning those decisions. It allows emergency physicians to operate at the top of their scope of practice.”

“But in many Australian EDs, and particularly when it’s overcrowded, the senior clinicians need to make the decisions and then they need to enact those decisions as well.”

“I don’t want us to move to that. But it’s interesting that there are still areas where we can still learn from how some of these other systems create efficiencies.

“One of the other important issues to acknowledge for emergency departments is that EDs are now managing complexity at scale. And then when the system becomes overcrowded.”

“And that leads to the moral injury of the healthcare workers who are constantly worried about the person in the waiting room that they don’t know about yet, who has a really serious condition and is quietly sitting there, waiting to be seen.”

“That is one of the major factors contributing to burnout and C-PTSD.”

Dr Herbert said he is proud of the effect of The Pitt.

“Doctors are getting help. Nurses are getting help. So it has had an incredible effect,” said Dr Herbert.

Dr Herbert said that now that the Trump administration is making even more cuts to Medicare and Medicaid in the US, emergency overloading may get worse.

“There’s going to be even more people.”

Becca Whitehead is a freelance journalist and health writer. She lives in Naarm and is a regular contributor to the MJA’s InSight+.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

The stress in Emergency Medicine in Australia is not the work. That is what we are trained to do. It is what we are good at. It is what we derive life and energy from. Caring for patients on the worst day of their life remains an immense privilege. The stress in Emergency Medicine is the systems which chronically fail to support us, and then blame us. For the wait times, for the delays to unit review, for the bed block. And when things inevitably go wrong because we can’t actually safely supervise the entire department and waiting room with one consultant working on the floor of a major city tertiary hospital. Where else in medicine do the consultants regularly get told that they are not working hard enough, not working fast enough, that “the numbers”are not good enough – and all the while we still haven’t had a pee since the start of our shift and our sandwich lies uneaten on the hot desk we got dragged away from 2 hours ago. We are chronically gaslighted that WE are the problem, when it has been utterly clear for 30y that the problems with EDs lie outside the ED. Bed block and inadequate resourcing are the permanent pachyderms in the room. Staff ED’s properly. Provide decent IT infrastructure. Address bedblock. Address other specialties that diss the ED and are obstructive. And watch our skilled ED physicians thrive

As a general surgeon performing emergency surgery, I’ve spent the last fifty years in and out of the ER. Things have definitely changed but you don’t need a TV program to tell you how good or bad it is. And there’s no point banging on about about under-staffing and under-resourcing. If Covid taught us one thing it is how unhealthy the general population is and how the current health care model – which was set up by the NHS 70 years ago – is no longer fit for purpose and is unsustainable (fixing things that are broken beyond repair). Politicians and jurisdictions such as RACS continue to run around like headless chickens. There is a total lack of leadership. The future has to be in prevention and a return to individuals taking responsibility for their own health. Otherwise we will reach a point of reverting to opiates to relieve the suffering. It will end in tears.

Interesting article, nice Australian connections, Adelaide actress in it too! I recall my somtimes impossible ED stints too. Great series depicting many of the issues – really well done! Problem is its now not just ED. Its right through the entire health system, full of ladder climbing administrators not managing the problems, bandaid solutions applied, neither respecting nor serving the doctors, nurses nor allied health workers doing their work at the real coal face. Wasting money on layers of management and not putting it into the actual service delivery. Our Surgical Unit deals with major trauma and acute care and cancer, very complex and high stress, BUT, we also deal with bed block, waiting lists, political sagas, mental health, violence, homelessness, aged care etc etc, handling policy failures of governments and management. Its sadly all about the Money now!! They waste reams of money trying to manage it inappropriately! I wish I could do a series on our version of the ‘Pitt’ in Surgery, same deal different area. Good on the writers and series in highlighting major real life issues and the system breakdown. There is a major urgent need to fix it!