The Public Health Association of Australia’s annual meeting brought together speakers with diverse viewpoints and perspectives on the seemingly intractable problem of preventive health in Australia.

‘Productivity’ is the word on everyone’s lips at the moment. The Albanese Government held a ‘productivity summit’ in Canberra in mid-August and, ahead of that event Health Minister Mark Butler ran his own round table aiming to square his patch — health, disability, and aged care — with the Government’s broader productivity narrative.

Nobody could reasonably dispute that a healthy population is more likely to be productive. Indeed, Treasurer Dr Jim Chalmers has put a ‘wellbeing’ lens over national policy:

“Australians are experiencing higher rates of chronic conditions and, in some instances, are finding it harder to access health, care and support services … Improving wellbeing is the job of government, business and other organisations as well as Australian communities and the Australian people.”

The Productivity Commission delivered its own report on the contribution of health to national productivity at almost the same time. That report was premised on the blindingly obvious: “As the population and its needs continue to change, the care system is coming under increasing pressure to deliver high-quality services at a sustainable cost.” Recognising that prevention of disease is the key to long term sustainability for our health system, the Commission’s interim report drove home the need for a ‘National Prevention Investment Framework.’

“A new approach to prevention investment is needed,” says the report. “Stopping problems from starting or getting worse — particularly for vulnerable populations — can result in better outcomes for individuals and the community. Investing in effective prevention can reduce demand for acute and more costly services down the track, helping to slow ongoing growth in government expenditure.” That is not rocket science.

The centrepiece of the Commission’s recommendation for a prevention investment framework is “a new national independent advisory board that would evaluate ongoing prevention programs and assess the cost-effectiveness of new programs.”

An economy that serves people, not profit

With remarkable prescience, the Public Health Association of Australia’s annual meeting, held last week in Wollongong, featured a panel session titled ‘Investing for wellbeing: How budget choices influence our health.’ I had the privilege of being a panellist with fellow panel members Commonwealth Health Department Chief Economist, Professor Emily Lancsar and Professor Cressida Gaukroger, a philosopher and wellbeing economy specialist.

The familiar contention is that economic growth delivers a stronger health system certainly is looking wobbly at the moment. Indeed, I recently reviewed Professor Rob Noonan’s book ‘Capitalism, Health and Wellbeing’ in which he presents very persuasive arguments that economic growth actually sacrifices individual health and wellbeing.

Professor Gaukroger pointed out that the Australian economy is centred around profit and growth, yet measures of growth such as gross domestic product (GDP) do not factor in the harms they generate. In fact, she argued, we need an economy designed to ‘serve people and the planet,’ not the other way around.

To put our human and environmental needs at the centre of all our activities will require major change. It will require a pivot to a system that better shares power and resources. Focusing on economic activity that favours jobs, businesses, production, and caring that is centred around improving and sustaining wellbeing. At the moment, Professor Gaukroger argued, our governments seem to be focused on the pursuit of strong GDP growth, which actively rewards industries and practices that are harmful.

Professor Lancsar brought to the panel her storied expertise and rigour in academic health economics. She made it clear that governments do at least recognise the importance of prevention and investment in preventive measures.

At the moment it is likely that the proportion of overall health expenditure devoted to preventive measures is less than 2%. Professor Lancsar presented data comparing health outcomes such as life expectancy compared to preventive expenditure, showing a somewhat woolly relationship between the two. “There is no magic percentage of health expenditure” that correlates well with population health.

Lancsar examined various counterfactuals and make the case that ‘preventive’ expenditure depends on what that spend buys in terms of improved health and wellbeing. Overall, she explained, Australia spends proportionally less on prevention than our OECD comparators – such as the UK, Canada, New Zealand and the US, but achieves overall better health outcomes.

Speaking like the veteran health economist that she is, Professor Lancsar argued for better analysis and use of cost-benefit as the basis of building cases for investment in preventive measures. This will require advances in causal analysis and in the use of linked data and of evidence at scale. She assured the audience that embedding measures of health-related quality of life in diverse data collections was definitely on the agenda.

An inconsistent approach to tackling risk factors

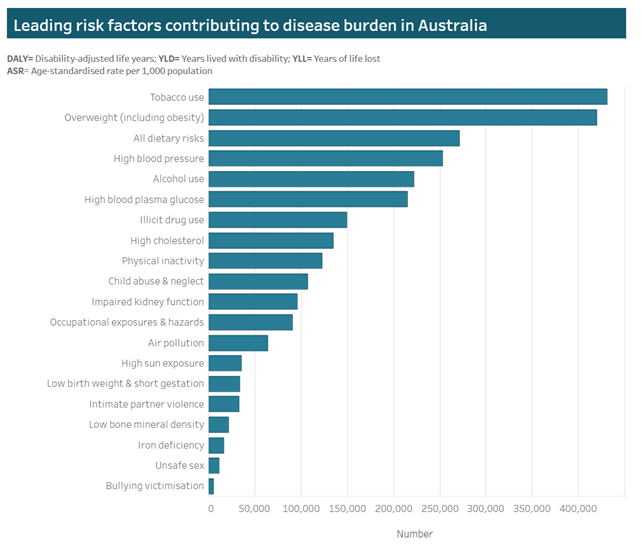

My own presentation centred around regulatory changes that could offer potential population-level preventive benefits — and why many of those evidence-based changes seem to be stalled. The top 20 risk factors that, collectively, drive over three million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) have been collated by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s Burden of Disease report.

Taking this graph as my starting point, I made it clear that Australian governments have, on occasion, put considerable effort into the regulatory and legislative responses required to tackle such causes of disease and injury as ‘occupational exposures and hazards’ [the 12th most important risk factor] and ‘bullying and victimization’ [the 20th most important risk factor].

When it comes to the 7th most important risk factor – illicit drug use – governments are prepared to pour $3.5 billion into mitigation every year. That tells us that governments are prepared to spend handsomely on prevention when it suits.

Similarly, long term government-led campaigns against sun exposure [the 14th most important risk factor] and physical inactivity [the 9th most important risk factor] are legendary. Who can forget the ‘Slip Slop Slap’ campaign, or ‘Norm’ telling us to get physical during the ‘Life be in it’ campaign?

Why, then, do we find ourselves in the position as a community where tobacco use, overweight and dietary risks, hypertension, alcohol use and high cholesterol — when all are combined — still account for over two million of the total yearly three million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for Australians?

Many of the risk factors for public health menaces such as obesity, alcohol misuse, tobacco and vaping, and online gambling harms must, at least in part, be tackled from a regulatory perspective. If it is that easy, then why haven’t governments taken action?

Obesity is a prime example of the principle that regulatory changes can, potentially, deliver public health wins. Many of the antecedents of adult obesity can be traced back to childhood dietary choices. These preferences are driven by marketing and there is strong evidence that “a broad prohibition on all forms of unhealthy food advertising online is desirable to protect not only children but also young people and the broader community.”

Advertising of unhealthy foods is rife and Australian studies of the materials children are exposed to on their school commute reveals the reach and extent of this influence. Unsurprisingly, there appears to be strong public support for government action against advertising unhealthy food to our children.

Why, then, is it so difficult for governments to mount a strong regulatory response that might protect us from this proliferation of unhealthy advertising? Could it be because unhealthy food advertising is a source of hundreds of millions of dollars of media advertising income? No government wants to take the risk of getting the nation’s media outlets offside.

Evidence must trump all else in health policy

Many potential ‘easy wins’ for preventive health are, unfortunately, politically difficult and this is something that public health advocacy bodies need to factor in to their policy output. During the panel session, Professor Lancsar was explicit that evidence should trump everything else when we consider health policy. We do indeed have a lot of evidence that regulatory change can deliver potentially big wins in areas like gambling harm, alcohol misuse, and encouraging us all to eat healthily.

Kudos to the Public Health Association of Australia for putting together a panel with speakers representing diverse viewpoints and perspectives on the seemingly intractable problem of preventive health in Australia.

Professor Steve Robson is chief medical officer at Avant Mutual. He is also chair of the National Doctors Health & Wellbeing Leadership Alliance, professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the Australian National University, and a council member of the National Health and Medical Research Council.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

An excellent article! Thank you for these useful insights. As you say prevention of illness is multi-faceted. The graphed causes of illness however do not capture the major influence of socio-economic factors on current and future health challenges.

Homelessness, the high cost of housing, diminishing access to stable and affordable housing are factors which are and will continue to influence health outcomes for children, families, single people, rural people, and low income people amongst others.

Historic information captured in government data provides part of the picture but what is happening in society and the economy is not captured by historic data. Supplementing the published data with active surveys and interviews is likely to indicated additional, powerful government actions which could prevent illness over this and the decades to come.