New guidance from Australia’s national privacy regulator clarifies clinicians’ discretion to contact a patient’s at-risk relatives directly about serious genetic risk.

Clinicians who order genetic tests know that for some genetic tests, a positive test result isn’t relevant only for the patient in front of us. Pathogenic variants in genes linked to predisposition to cancers, heart disease or other conditions come with significant risks, not only for patients, but also for their blood relatives. Using cascade testing, we can identify who else in the family may carry the same variant and offer timely interventions. For younger relatives in particular, this knowledge can be life-saving. Moving into a space where we use genomics to prevent disease, rather than just to diagnose or treat it, is my life’s passion. The DNA Screen study, which I co-lead, is piloting the offer of preventive genomic information to the whole adult population.

Often, however, there’s a major sticking point once we know about genetic risk in the proband: telling the family. Some patients are uncomfortable making contact. Others may be estranged, uncertain of how to have the conversation, or simply overwhelmed. The rate of cascade testing of at-risk relatives is estimated to be less than 50%. As clinicians, we might be asked: “Can you tell them for me?”.

Research tells us that when clinicians do notify relatives directly, cascade testing uptake generally increases. In a 2005 study done in South Australia to test this, the directly notified cohort had double the cascade testing uptake of the “usual practice” cohort. Despite this, many Australian clinicians have been hesitant to act, fearing it might breach privacy laws. Thanks to updated guidance from the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), however, we now have clear, national guidance that supports clinicians’ discretion to notify at-risk relatives directly, without breaching the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth).

What the updated guidance means

Over the past two decades, Australian law has evolved to allow clinicians to notify genetic relatives without patient consent in specific circumstances. These are laid out in the National Health and Medical Research Council s95AA guidelines. But in the situation where patients do consent, even though it seems obvious that this would be allowed, clinicians have reported uncertainty. Some are worried that using a relative’s contact details (even with consent from the patient) could breach the relative’s privacy. Others are confused about how the Privacy Act applies.

To address this, I sought clarification in 2024 from the OAIC — Australia’s national privacy regulator. Following discussions with the OAIC, it updated Chapter 8 of its Guide to health privacy in 2025 to clarify the position. The revised guidance confirms that clinicians can collect a relative’s contact details from a patient and use those details to notify the relative of their genetic risk, where the patient consents and the risk represents a serious threat to life, health or safety. Importantly, the guidance states that in these circumstances, collecting a relative’s contact details without their prior consent is permitted under the law, because it would generally be impracticable to obtain it otherwise.

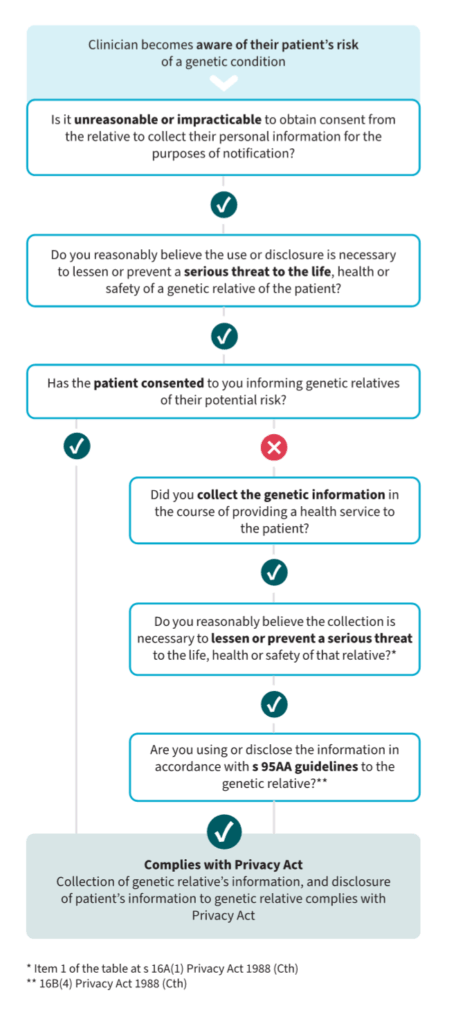

This update confirms what I had previously argued: if you have consent from your patient, and the risk is serious and actionable, you can contact their relatives directly about possible genetic risk. The OAIC has even created a simple flowchart to support clinical decision making.

Do patients and the public support this?

It’s not just clinicians calling for clarity, patients and the public overwhelmingly support this too. We’ve surveyed hundreds of patients and over 1000 members of the general public. The majority of people said they wanted to be told if they were at risk of a serious genetic condition. Although some said they preferred to receive notification from their family members, many even preferred to be contacted by a health professional about their risk. We asked specifically if people had privacy concerns about this, and they were minimal.

The idea of a “right not to know” is often raised in discussions about genetic risk notification, and it’s important to consider. But in practice, there is no difference in this sense between clinician-led contact and patient-delivered “family letters,” which are the current standard. In both cases, the patient decides who should be informed. Importantly, this discretion only applies where the risk is serious, and the health threat can be lessened or prevented, making the argument for public interest in disclosure even stronger. Further, it is difficult to support true autonomy (making an informed choice) if at-risk people are not even told about their risk and given the opportunity to make that choice.

Where to next?

Now that the national privacy regulator has confirmed that direct notification is legal under the Commonwealth Privacy Act, clinicians need tools and support to know how to put this into practice. National clinical guidelines would help with this, particularly around when the “serious threat” threshold is met, and how to document consent and communication. We also need consistent interpretation across jurisdictions. Although the OAIC’s guidance applies to clinicians working in the private sector (who are subject to the Commonwealth Privacy Act provisions), clinicians working in the public sector are also governed by state and territory regulations. My earlier legal review argues that the same principles that have been confirmed by the OAIC are consistent across all jurisdictions, but state and territory level clarification would provide reassurance to clinicians.

Finally, clinicians must be able to exercise their discretion without fearing that it will create a rod for their backs. The OAIC’s guidance makes it clear this is a discretion, not a duty. The current law doesn’t require clinicians to contact every relative of a patient, but if a patient does want us to help with contacting their relatives, we now know we can say yes.

This update is a win for patients, their families, and the clinicians who support them. It brings clarity to a long-questioned legal position and paves the way for more effective cascade testing, and, ultimately, the use of genomics for better disease prevention.

Dr Jane Tiller is a lawyer, genetic counsellor and public health researcher. She is Ethical, Legal and Social Adviser in Public Health Genomics at Monash University.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Is there a list of agreed genetic findings that meet the threshold? For example huntingdons disease is autosomal dominant and active treatment is now available and may accelerate after trial results in September; but whatabout genetic causes of for example Alzheimers, ranging from direct genetic causes eg psen mutations to say apoe4 status which can affect up to 11% of the population?

The difficulty in the advice is the subjective nature of “serious threat to life”. Is this short term risk or life time risk? Is the risk 0.1, 1.0, 10 or close to 100% risk? If the genetic marker doubles the risk of an adverse event, but the event itself has low absolute risk (so minimal increase in risk). None of these questions of proportionality are addressed.

I fully support the notion of giving patients the relevant information and encouraging them to pass this onto relevant family members. I routinely encourage do this for patients with bicuspid aortopathy (50% risk in first degree relatives) and also cascade testing for patients with Familial Hypercholesterolaemia. But I have had patients with BRCA positive cancer who do not want their relatives to know of their diagnosis & refuse (as best I know) to pass on the info.

IMO, my role is to make the recommendation, and beyond that patient confidentially remains critical. Furthermore, I do not possess the contact details of the first degree relatives etc.

I don’t see any clear way the article addresses these questions.