Rising incidence of gastro–oesophageal cancers

The incidence of types of stomach and oesophageal cancers is rising in Western societies and younger populations, making these conditions significant public health issues. In Australia, in 2024 the age-standardised incidence for stomach cancer was 7.6 per 100 000 persons and 5.1 per 100 000 persons for oesophageal cancers. Importantly, despite advances in diagnostic modalities, surgical approaches, anti-cancer therapies, and supportive care, stomach and oesophageal cancers have a disproportionally high mortality rate compared to the average 5-year overall survival for all cancers combined (at 71.2%), with 5-year overall survival rates of 38% and 23% respectively.

Most gastro–oesophageal cancers are diagnosed late

Patient prognosis is dependent on tumour stage at presentation for both stomach and oesophageal cancers. Cancers diagnosed early (restricted to the mucosal layer) carry a favourable 5-year survival rate of more than 70%. Unfortunately, long term survival rapidly declines with deeper invasion or regional nodal involvement, with a 5-year survival rate of ~20 to 40%. When patients present with metastases in the peritoneum, distant organs or non-regional lymph nodes, their 5-year survival rate is ~5% for oesophageal and ~7% for stomach cancer. The pressing issue is that less than one-third of patients are diagnosed with early disease.

Delays in cancer diagnosis are common

The majority of patients diagnosed with cancer present initially to their primary care physician. Data indicate that more than 80% of these patients report at least one red-flag symptom or sign that is predictive of underlying gastro–oesophageal cancer (Table 1). The presence of these red-flag symptoms without a clear explanation should prompt consideration for endoscopic and gastrointestinal specialist referral. However, data from a UK study indicate that nearly a quarter of all patients with any symptoms received three or more consultations with their general practitioner before a hospital referral. Another UK study found that this often amounts to more than 90 days delay in reaching a cancer diagnosis. Such an extended period without anti-cancer treatment may translate into disease progression and could compromise patient outcomes.

Reasons for diagnostic delay are multifactorial and likely reflects patient, disease and system issues. Often, the reported symptoms are vague and overlap with other more common diagnoses. Furthermore, these symptoms may be relieved, albeit temporarily, by dietary modifications, proton pump inhibitors, and anti-emetic and analgesic agents, thus falsely reassuring the treating doctor. Additionally, there may be a lack of awareness of the changes in incidence and presentation of gastro–oesophageal cancer in our society and how this condition manifests clinically. Critically, there are no robust risk assessment tools at the general practitioners’ disposal to guide clinical decision making and referral pathways. Overlying these dilemmas are issues of access to hospital endoscopy services, particularly for regional and remote patients. These issues include opaque referral pathways, lengthy public waitlists, and under-resourced outpatient departments resulting in inefficient triaging and coordination of care.

Developing resources to assist general practitioners in expediting cancer diagnosis

To enhance gastro–oesophageal cancer management at the primary care level, the authors, in collaboration with Bristol-Myers Squibb Pty Ltd, have developed a pragmatic education brochure – Understanding Oesophagogastric Cancer’. This brochure has been electronically circulated to more than 2700 general practitioners across Australia through the Australasian Medical Publishing Company, the Royal Australasian College of General Practitioners, and Medicines Today. In alignment with the Cancer Council’s Optimal Care Pathway guidelines and Cancer Australia’s Australian Cancer Plan 2023–2033, this brochure seeks to:

- raise awareness of the importance of timely diagnosis;

- highlight patient subgroups who are at high risk of developing gastro–oesophageal cancer (Table 2);

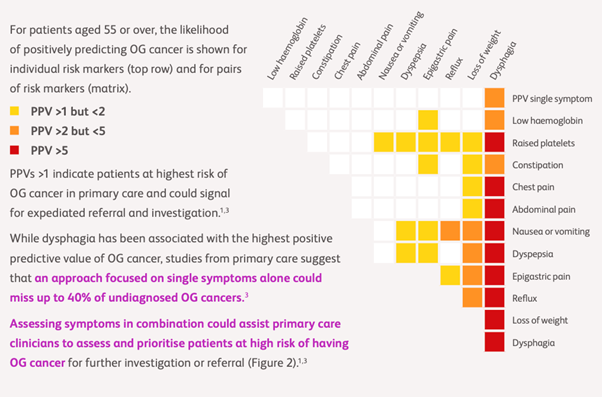

- provide a practical aid for assessing the likelihood of underlying gastro–oesophageal cancer based on presenting symptoms and signs (Figure 1); and

- clarify endoscopic referral pathways and triaging criteria for Australian hospitals.

Our hope is that this resource will encourage timely specialist and endoscopic referrals for patients who present with red-flag symptoms and signs of gastro–oesophageal cancer.

Much more needs to be done to expedite cancer diagnosis

Early access to endoscopy is critical to making a diagnosis. To avoid triaging delays, it is important for referrals to include clear symptomatology highlighting the presence of dysphagia and other red-flag symptoms.

Open access endoscopy through public hospitals and private centres are alternative avenues for rapid endoscopy access. This bypasses public outpatients burdened by extended waitlists. Rural communities face greater challenges with access to endoscopy, especially through the public system compared to the private system. Therefore, discussing open access private endoscopy with patients or direct referral to a gastrointestinal specialist without prior endoscopy is important as many may elect to pay for these services rather than wait for access through the public system.

More broadly, other efforts such as eliminating unwarranted practice variations at the primary and tertiary care levels, conducting public awareness campaigns targeting gastro–oesophageal cancer, and identifying high-risk patient subgroups to economise screening programs could contribute meaningfully to achieving an early diagnosis.

Take home message

Funding is urgently required to support a locally validated tool for general practitioners to determine cancer risks. Consider early referral to endoscopy and/or gastrointestinal specialist for patients with red-flag symptoms (Table 1). A timely diagnosis could improve outcomes of patients with gastro–oesophageal cancer.

| Dysphagia |

| Epigastric pain > 2 weeks |

| Dyspepsia |

| Odynophagia |

| Food bolus obstruction |

| Unexplained weight loss or anorexia |

| Haematemesis or melaena |

| Early satiety |

| Unexplained nausea/abdominal bloating or anaemia |

| Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma | Oesophageal adenocarcinoma | Gastric adenocarcinoma |

| Age > 60 years Heavy alcohol consumption Smoking Caustic injury to the oesophagus Achalasia |

Age > 60 years Male Obesity Gastro–oesophageal reflux disease Barrett’s oesophagus Heavy alcohol consumption Smoking |

Age > 60 years Helicobacter pylori infection Previous gastrectomy Smoking Heavy alcohol consumption Pernicious anaemia Family history of stomach cancer |

(PPV = positive predictive value; OG = oesophagogastric)

Associate Professor Audehm is a general practitioner who has worked for over 35 years in general practice and is experienced in managing all types of patients. He is an Honorary Clinical Associate Professor in the Department of General Practice and Primary Care, University of Melbourne.

David Liu is an oesophago-gastric and general surgeon at Austin Health and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Victoria, Australia. He is also an Associate Professor within The University of Melbourne, Department of Surgery. David has a passion for service innovation, translational biology, and clinical collaborative research, focusing on malignant upper gastrointestinal diseases.

This article has been commissioned by Bristol-Myers Squibb Australia Pty Ltd (BMS). BMS has had no influence over the expert commentary for this review, which is entirely independent and may not necessarily represent the opinion(s) of BMS. BMS abides by the Medicines Australia Code of Conduct and our own internal policies, and as such will not engage in the promotion of unregistered products or unapproved indications. Treatment decisions are the full responsibility of the prescribing physician.

Date of Approval: April 2025. ONC-AU- 2500044.

more_vert

more_vert

Well presented & a very helpful guide to better care. Thank you