The updated guidelines for osteoporosis management and fracture prevention are an evidence‐based pragmatic tool designed to support general practitioners in the treatment and management of at-risk patients.

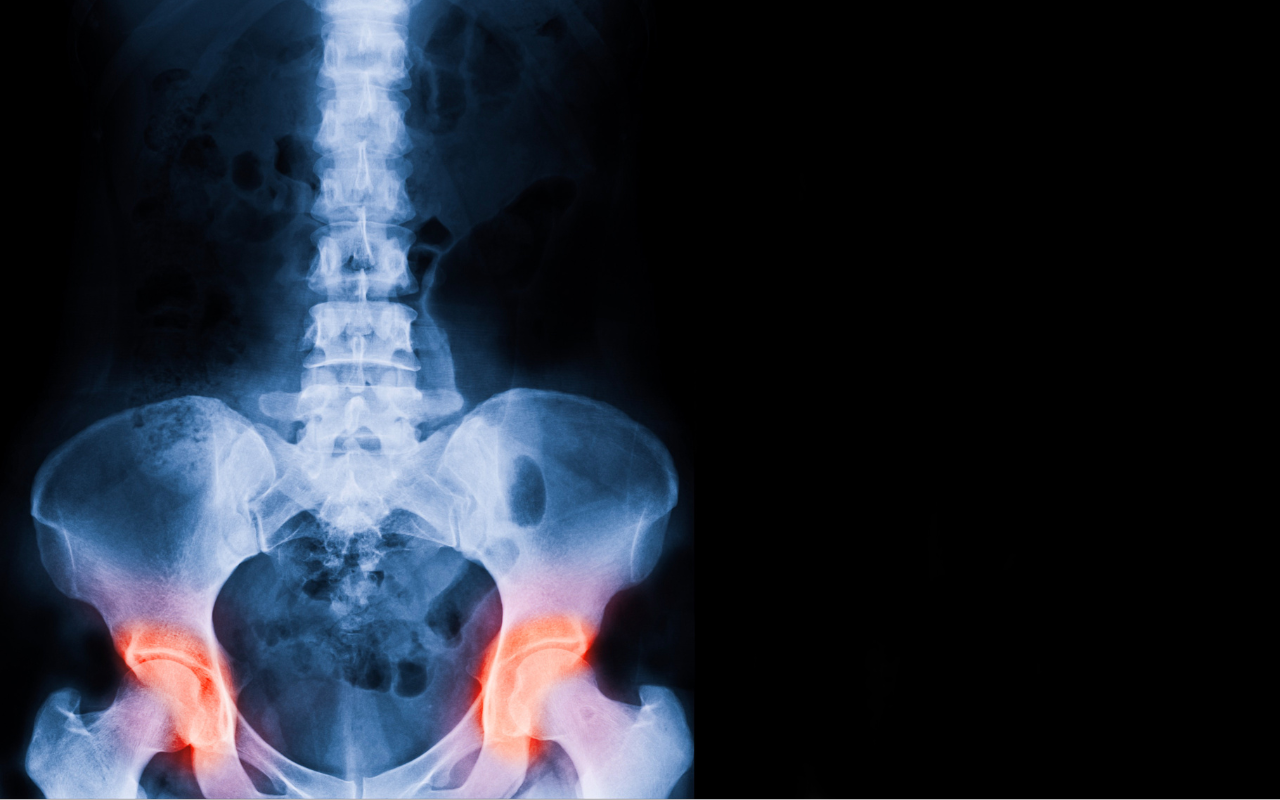

Osteoporosis, which is characterised by low bone mineral density (BMD) and bone tissue deterioration, affects 66% of Australians over the age of 50.

The deterioration of skeletal tissue is asymptomatic until a fracture occurs. Hence, early detection is vital for preventing the significant morbidity and mortality that accompanies fractures.

Healthy Bones Australia was contracted by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care to update the 2017 guidelines for osteoporosis management, and a summary of this update has now been published in the Medical Journal of Australia.

The update focuses on improvements in clinical practice, the need for expert consensus and opinion, and new developments in pharmacological management.

“The updated guideline was designed to provide clear, evidence‐based recommendations to assist Australian general practitioners in managing patients over 50 years of age with poor bone health (osteopenia and osteoporosis),” Professor Peter Wong of Westmead Hospital and co-authors write.

“Its purpose was to support, not replace, clinical decision making in the individual patient, and to assist busy general practitioners in achieving better patient outcomes.”

Assessing clinical risk factors

The updated guidelines provide clearer advice on which fracture absolute risk calculator clinicians should be using in routine practice.

The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) is recommended, noting that clinical judgement remains essential for interpretation, while the Garvan Fracture Risk Calculator is also a convenient option for patients who experience a fall.

In trials developed for the guideline update, a two-step process of initial FRAX assessment was used to guide the need for BMD measurement by dual‐energy x‐ray absorptiometry (DXA).

“The absolute risk at which to recommend DXA and the threshold for commencement of pharmacotherapy is important, yet not consistently defined,” the authors write.

“A slightly lower threshold for recommending BMD has been adopted, as was done in the SIGN guidelines 2021, where a ten‐year risk of major osteoporotic fracture of more than 10% triggers a recommendation for BMD measurement, which is relatively pragmatic and inclusive.”

Clinicians can find a guide to DXA testing, including Medicare Benefits Schedule item numbers, here.

Imminent and very high fracture risk

Identifying patients with very high fracture risk is crucial due to the increased risk of fracture in the 24 months following an initial fracture. These patients may also be candidates for osteoanabolic therapy, which is becoming increasingly available.

Features that would indicate a patient is very high risk include:

- recent fracture and a ten‐year FRAX major osteoporotic fracture risk of 30% or over;

- a recent fracture (within 12 months);

- a T‐score below ‐3.0;

- multiple fractures while on therapy;

- the use of drugs causing skeletal harm; and

- a ten‐year FRAX major osteoporotic fracture risk of 30% or above, or hip fracture risk of more than 4.5%.

Calcium, vitamin D and protein supplementation

The updated guideline discusses a vast amount of literature published on the use of calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

“The absolute benefit of calcium and vitamin D supplementation for short term (less than five years) fracture prevention for non‐institutionalised individuals is relatively low and much less than with pharmacological treatments, such as bisphosphonates or denosumab,” the authors write.

Protein supplementation is also discussed, with a Melbourne study showing a significant reduction in falls risk and fractures in institutionalised older adults who had improved calcium and protein intake from dairy food products.

The guideline notes that calcium, vitamin D and protein supplements are more likely to be effective in reducing fracture risk when an individual is deficient, therefore the guideline recommends supplementation be targeted towards people who are frail, institutionalised, or receiving bone-protective therapy.

Osteoanabolic therapies

There have been changes to the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS)‐subsidised therapeutic options for poor bone health since the previous guideline, with the removal of strontium ranelate and the addition of romosozumab.

Romosozumab, which increases bone formation and reduces bone resorption, has received a first-line PBS listing for patients at very high fracture risk.

“This will allow initiation of potent bone anabolic therapy in treatment‐naïve patients to be sequentially followed by antiresorptive therapy (eg, bisphosphonate or denosumab) to achieve and maintain the greatest possible gain in BMD,” the authors write.

The guideline notes that antiresorptive therapy denosumab should be continued long term or its cessation followed by antiresorptive medication to avoid a rebound of bone resorption and vertebral fractures.

“Most general practices have a robust recall system to ensure denosumab administration occurs at the specified six‐monthly intervals to minimise the risk of rebound vertebral fractures,” the authors write.

Read the guideline summary in the Medical Journal of Australia.

Read the full guidelines at Healthy Bones Australia.

Listen to the MJA podcast on the guidelines with Professor Peter Wong

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

more_vert

more_vert