This World Kidney Day, we highlight Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD), which affects about one in 1,000 people. New Australian guidelines have been developed to diagnose and manage this disease, with support available through PKD Australia.

Kidney failure is common in our community, with 28 500 Australians living on dialysis or with a kidney transplant. Until recently, the cause of kidney failure in many people was often uncertain, especially in young people or those with familial kidney disease. This was because many patients already have end-stage kidney failure when they present for medical care and at a time when their kidney biopsy shows scarring and irreversible damage, with no clues to the original cause of disease.

However, local and international studies have demonstrated that at least 10% of patients with kidney failure have a genetic cause. Genetic testing enables us to make an accurate diagnosis of genetic disease. Diagnoses that were previously thought rare or only found in children are being identified in our patients even in late middle age.

Spotlight on autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

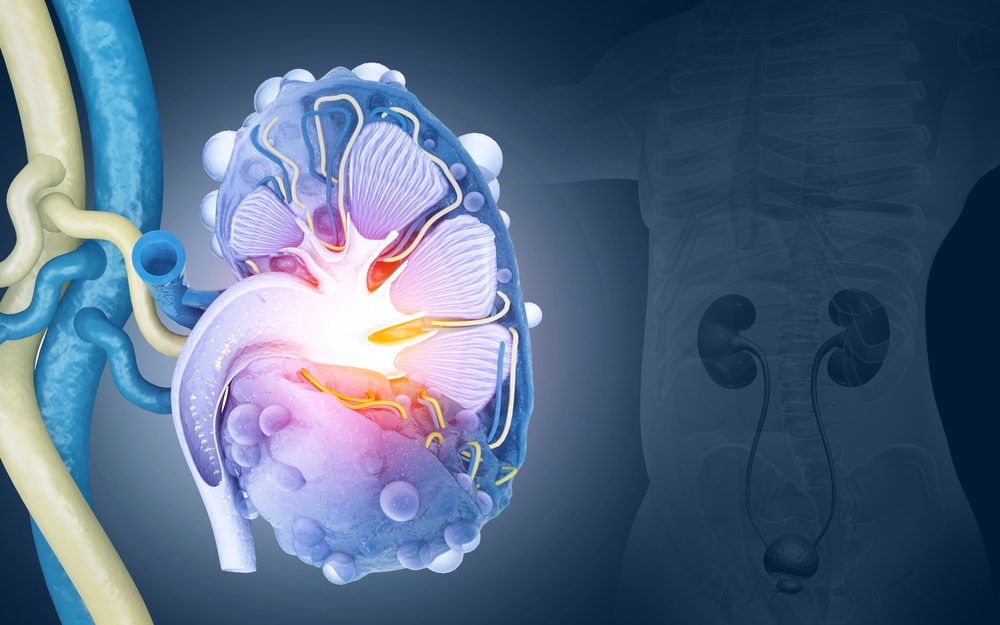

The most common cause of genetic kidney failure in adults is autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), which affects at least one in 1000 people and represents approximately 10% of the patients with kidney failure. ADPKD is a disorder characterised by the growth of numerous cysts in the kidneys, leading to kidney enlargement.

Approximately 50% of people with ADPKD develop kidney failure by about 60 years of age. ADPKD is primarily caused by variants in the genes PKD1 or PKD2, which encode proteins involved in kidney cell structure and function. Diagnosis and treatment of ADPKD involves a multifaceted approach aimed at managing symptoms, slowing disease progression, and addressing associated complications. A rare type of polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is autosomal recessive PKD (ARPKD) which is usually diagnosed at birth, occurs in one in 20 000 people, and is caused by variants in PKHD1.

The diagnosis of ADPKD typically involves a combination of history, family history, physical examination, and kidney ultrasound, and in selected situations, genetic testing is required. ADPKD is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning that affected individuals have a 50% chance of passing the condition to each child they have. This multigenerational aspect distinguishes ADPKD from non-inherited chronic kidney diseases (CKD), emphasizing the importance of genetic counselling for affected individuals.

Chronic pain related to kidney cysts is also a significant issue for patients with ADPKD. In addition, psychosocial impacts of ADPKD can be significant, affecting quality of life, mental health, and relationships. Patients may experience anxiety, depression and stress related to the progressive nature of the disease, as well as potential complications such as hypertension and kidney failure, and concerns about passing the condition to future generations.

Considerations for general practitioners

It is important for general practitioners to undertake an early referral to a nephrologist for managing ADPKD effectively and improving prognosis through access to newly approved therapeutics, such as tolvaptan, and enrolment in clinical trials of novel treatments. Nephrologists will monitor kidney function, blood pressure, help coordinate the care of any extra-renal manifestations of ADPKD, and assist in managing symptoms related to kidney cysts or impaired renal function. Investigations to perform prior to nephrologist referral include kidney ultrasound, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR; current and historical values), and spot urine albumin to creatinine ratio.

For people affected by ADPKD, a common question is around whether other family members (particularly children and siblings) have also inherited the condition. The CARI-ADPKD guidelines recommend genetic counselling prior to screening asymptomatic, at-risk relatives (whether this is by ultrasound or genetic testing). Genetic counselling provides the opportunity for at-risk individuals to consider the possibility of having inherited a chronic disease and consider possible family and insurance implications of a predictive diagnosis.

It is important to note that a kidney ultrasound that detects cysts in someone whose parent has ADPKD is often diagnostic of the disease. Therefore, it is vital that at-risk patients should be counselled on this before undergoing renal ultrasound. There usually is no requirement for people with ADPKD or at-risk of ADPKD (especially children) to have surveillance imaging, unless there is a clinical indication for imaging (eg, investigation of abdominal pain).

Genetic testing is “vital”

Medicare funding has recently become available to subsidise genetic testing for patients suspected of having ADPKD, making this investigation more accessible. Genetic testing plays an increasing role in the diagnosis and management of ADPKD, offering opportunities for early detection, risk assessment, and informing family planning decisions, such as pre-implantation genetic diagnosis. Nephrologists and clinical geneticists can facilitate genetic investigation in families. Funding is also available for genetic testing of at-risk family members.

Identifying the specific genetic cause of ADPKD in a family can allow patients to access assisted reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), in which embryos can be screened for a known familial genetic change and an unaffected embryo then implanted for a continuing pregnancy, therefore avoiding passing on the condition. Medicare funding has also recently become available for genetic testing of embryos in this situation. Families seeking information on their risk of passing on ADPKD and reproductive options available to them can be referred for genetic counselling.

The majority of people with ADPKD have a clear family history of the condition. However, about 10% of those with ADPKD are the first affected in their family and, therefore, have no family history of the condition. A diagnosis of ADPKD should be considered in people with an increased number of kidney cysts for age or enlarged kidney size. These patients could be referred to a nephrologist for further assessment.

Support for clinicians and patients and their families

Improving care for families with ADPKD is an active research area in both clinical and basic science research. The charity, PKD Australia, is a strong champion of PKD research in Australia and supports a wide range of research projects. The Australasian Kidney Trials Network is leading a multicentre international randomised controlled clinical trial (IMPEDE-PKD), which investigates the efficacy of metformin in reducing the loss of kidney function. Australia has led genomics research in ADPKD, having led the development of a new whole genome sequencing genetic test for families with ADPKD. The Westmead Institute for Medical Research led the PREVENT-ADPKD trial (which evaluated the role of increased water intake to slow progression) as well as the BEET-PKD trial (to be reported in 2024). In basic science, Monash University has identified a key kinase involved in the development of PKD. Researchers at the Garvan Institute and the KidGen Consortium are also currently conducting genetic studies aiming to identify the genetic basis of disease in undiagnosed families with PKD and studying the molecular reason that kidney cysts develop in the disease.

Australian Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of ADPKD have been developed through the CARI Guidelines group, and include a living guideline focused on pharmacological management. These Guidelines have been developed in conjunction with consumers and content experts.

PKD Australia is the leading consumer support body for families with PKD, and has developed consumer-led fact sheets for people affected by PKD which provide a valuable resource for those seeking accessible information.

Dr Amali Mallawaarachchi is a clinician scientist at the Department of Medical Genomics at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research.

Associate Professor Aron Chakera is a renal physician in the Department of Renal Medicine at the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Perth.

Professor Judy Savige’s work focuses on the genetics of kidney disease at the Department of Medicine (Melbourne Health and Northern Health), Royal Melbourne Hospital and the University of Melbourne.

Professor Gopi Rangan is clinician-scientist/nephrologist in the Department of Renal Medicine, Westmead Hospital, and at Centre for Transplant and Renal Research, Westmead Institute for Medical Research at The University of Sydney, and focuses on translation research in ADPKD.

Robert Gardos is Chairman of PKD Australia.

Helen Coolican is founding co-director of PKD Australia.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Yes definitely!!! I have poly cystic diease and I have had two seperate crainiotomys.

So two separate brain aneurysms.

Should patients with ADPKD (and perhaps their families) be screened for cerebral aneurysms?