Health systems need to adopt a workplace culture centred on human wellbeing to build a healthy workplace culture that is fit for the modern era. Psychosocial hazard policies could be effective levers to drive this change.

For too long, doctors and other health care professionals across Australia have endured poor organisational culture and leadership when it comes to tackling bullying, harassment, other negative workplace interactions, and system performance.

These psychosocial hazards must be defined and addressed by health leaders to prevent any more psychological harm to staff and to encourage more of our colleagues to stay on the frontline of health care.

A psychosocial hazard is anything that could cause psychological harm (here). Common psychosocial hazards at work include many items such as poor organisational change management, bullying and harassment and poor workplace relationships and interactions. Occurrence of burnout, bullying and harassment, mental illnesses, racism and suicide among health workforce and difficulty implementing health equity programs have attracted media and political attention in the recent times; and emphasised the need for improving psychosocial safety within health systems. The most recent 2023 Medical Training Survey showed bullying, harassment, discrimination or racism was experienced or witnessed by 35% of all trainees and 54% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander trainees, most commonly by more senior clinicians.

Policies related to psychosocial hazards and the concept itself were developed to protect the wellbeing of the workforce, and these kinds of policies are vital for quality improvement purposes within a health care context.

Recently, workforce wellbeing has taken the centre stage, and before that, workforce engagement was the dominant theme. Having experienced emotional distress and moral injury while leading telehealth-related reforms to address health inequities faced by regional, rural, remote and Indigenous populations, I believe that wellbeing and engagement issues are symptoms of one disease, “poor workplace culture”, rather than separate and unrelated problems. Wouldn’t it make sense to cure this disease rather than focusing on palliation alone?

There is another interesting observation. Every new person to the role talks about “culture reset”, but they tend to do the same thing that was tried before. Common action then seems to focus on leadership training initiatives that produced mixed results in the literature (here). Culture within health systems and services itself is not addressed comprehensively while Royal Commissions and many system reviews continue to call for cultural reforms.

It seems that there are two main problems. If culture has been an ongoing issue, why then leave it to the same people or sections that failed to improve culture in the first place? The second issue is the focus on personal behaviours as the foundation for culture without factoring in system behaviours and system management structures (here and here). Current culture frameworks and guidelines tend to operate within the confines of hierarchical and autocratic systems, vary in contents and definitions and do not align fully with the psychosocial hazards either. To create consistency within the Australian health care context (supposedly underpinned by democratic principles), our organisation Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA), a peak national body for cancer care workforce, has initiated a project that aims to develop a national framework for healthy workplace culture drawing from existing guidelines and frameworks. This draft framework can be found on the COSA website and can be applicable to all human-centred workplaces, not just health care settings or cancer care sector.

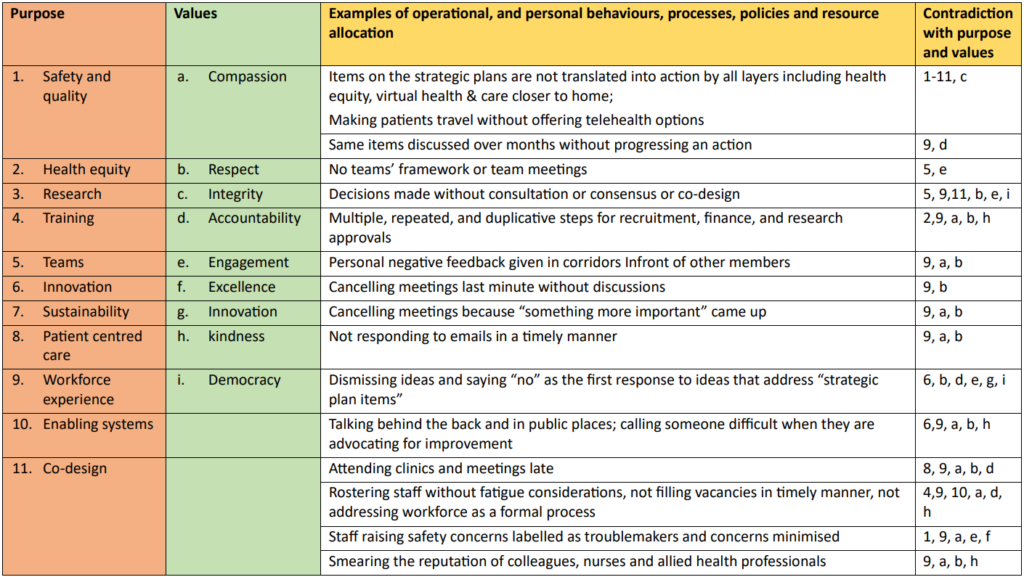

Healthy workplace culture is where the whole organisation aligns with its purpose and values. Therefore, anything that contradicts with the purpose and values will lead to poor culture and moral injury, will damage wellbeing, and will, therefore, be deemed psychosocial hazards. Purpose is addressed by strategic plans, and failure to address all the items is an indication of how well an organisation is performing. For example, when health inequities are listed as a priority and actions related to this are not even addressed in agenda items across the layers, it is an example of misalignment with purpose, or in lay terms “lip service”.

In my reflection, difficulty in closing the gap for rural and remote regions and Indigenous communities could be related to this misalignment or lack of commitment within organisations. These examples can be highlighted as psychosocial hazards so that systems can be forced to align with purposes expected by our communities. I’ve listed some examples in Table 1.

Values alignment has been mainly attributed to personal behaviours without realising that our workforce is largely made up of educated and passionate adults. Poor behaviours are usually in reaction to poor system factors and actions though a minority may be disrespectful and uncompassionate as their primary mode of interpersonal interactions. The COSA framework and Safe Work Australia’s psychosocial framework consider a similar holistic set of system factors as a requirement for healthy workplace cultures and workforce wellbeing respectively. They include “values aligned interprofessional interactions, operational behaviours, policies, programs, procedures, and resource allocation.”

For example, if an approval process is developed without codesign, adds unnecessary and meaningless work to the already stretched workforce, and causes delays in progressing straightforward items, that process is not compassionate, accountable or respectful. Of course, staff will then react due to frustration. This means every organisation and their layers need to review and update processes and policies and make sure they remain contemporary and fit for the purpose of enabling our workforce to do meaningful work. This will avoid poor personal behaviours, achieve better engagement with work and productivity and ultimately lead to a mentally healthier workforce.

This reform requires high performing teams across all layers of the organisation(as I wrote here, page 22). We need consistent national checklists tailored for health context to guide the development of teams so that the quality and capabilities of teams could be consistent across the system regardless of the quality and capabilities of team leaders. In the absence of team frameworks, we will end up with a group of individuals working under a framework largely dictated by one or two individuals. Diversity, inclusion, multidisciplinary input, empowerment, sense of belonging, collective leadership and engagement can all be addressed formally through team-based operations. Formal inclusion of junior members within health care and management teams allows not only diversity of thought processes, but also leadership and professional development on the job. In terms of monitoring and enabling of team functions, we could then use compliance with team’s framework to foster team culture. Psychosocial hazards policies could then be used to escalate poor team operational and personal behaviours not only to improve wellbeing but also to foster team morale and enhance performance.

In summary, psychosocial hazard polices need to be implemented along with cultural reforms and be incorporated into existing workflows to be fully effective. They should not be treated as another stand-alone policy that could be tick-boxed by forming separate committees and working groups.

I encourage politicians, health sector leaders and medical leaders to look at COSA’s draft framework if they truly believe in improving workplace culture and protecting the wellbeing of our already stretched workforce. These reforms need to be led by senior leadership in a health care setting, in partnership with human resources practitioners and all layers of the system for whole-of-system adoption and sustainability.

Professor Sabe Sabesan BMBS PhD FRACP is President-Elect, Clinical Oncology Society of Australia; the Clinical Dean of the Townsville Medical Training Network; and a Senior Medical Oncologist at the Department of Medical Oncology at the Townsville Cancer Centre.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

It does not necessarily matter what “we” say or sometimes do in respect of workplace culture, when the underlying behaviour, due to inadequate funding and a culture of driving junior doctors to do more with less, and not to pay unrostered overtime, is that it means that the young doctors will perceive that the underlying structure and culture is to demean them. Two aphorisms are relevant: ‘what we do is more important that what we say”, and after Drucker, “culture eats strategy for breakfast”.

Great summary of current challenges in healthcare organisations large and small. The lack of clarity in the purpose of the organisation can create significant dissonance which impedes progress to adopting processes and ways of working which are fit for purpose driving disengagement and frustration which are occasionally articulated as poor behaviour. This also cannot be excused or condoned. Completely agree effective system design and configuration is the main driver of workplace culture and placing the onus on individual behaviours avoids making the hard decision and undertaking challenging capability developments that are required to change the outcome.

Thank you for this timely article . I agree that workplace culture is the central driver of workforce malaise . Yet so many wellbeing interventions are targeted at individuals. It was very helpful to see a framework for understanding the issues in the table provided . Great food for action .

Unfortunately we as doctors are also culprits in this through our actions. Training surveys suggest bullying and harassment continue to exist. Also some of the obstruction to progress within health systems come from nurses, doctors and allied health staff.

Bureaucrats love rules ands protocols – that is how they justify their existence. Doctors exist to care for patients.

Kindness and respect in the workplace should NEVER have to be mandated – if it is, we have failed miserably in our selection and training, and in our own duties of care.

Allowing bureaucrats to dictate what they believe is “psychologically safe” puts all doctors and their patients at risk.

Just be kind and respectful. No matter whether it is made a rule by bureaucrats or not!