More young people are being diagnosed with colorectal cancer in Australia, a disease that is frequently diagnosed in its later stages.

More funding is needed for public colorectal cancer treatment centres in Australia, with the demand for care, especially among younger people, expected to increase.

Improved referral pathways are also needed to ensure that people with advanced colorectal cancer have access to all available treatment options, according to a Perspective published in the Medical Journal of Australia.

Dedicated colorectal cancer units are able to deliver complex procedures for patients, Dr Kilian Brown, Dr Nabila Ansari and Dr Michael Solomon wrote.

“[The units] are able to deliver complex surgery (such as pelvic exenteration, cytoreductive surgery, and metastectomy), local ablative treatments by percutaneous approaches or stereotactic radiotherapy, as well as access to novel systemic treatments and clinical trials,” wrote Dr Brown and his colleagues.

Key statistics

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in Australia, with an estimated 15 367 new cases diagnosed in 2023 (8133 men and 7234 women).

In recent decades, the number of people under the age of 50 years developing the disease has increased, while incidence in the number of people older than 50 years has decreased.

Surviving bowel cancer is highly dependent on the stage at diagnosis. For people diagnosed with stage I bowel cancer, the five-year relative survival rate is 99% compared with 13% for those diagnosed at stage IV, when metastatic disease is present (here).

A Victorian study found that 24% of patients with colorectal cancer had metastatic disease at or within four months of diagnosis.

Evolution of treatments

“Treatment of [colorectal cancer] has evolved dramatically in the 21st century, particularly for patients with advanced disease,” Dr Brown and his colleagues wrote.

“Advances in medical imaging and peri-operative medicine, as well as refinement of surgical techniques, have facilitated radical resection in selected patients with advanced or recurrent local disease, as well as those with limited metastases, who would otherwise be considered incurable.”

The developments also mean that people with metastatic (stage IV) colorectal cancer who historically had few systematic treatment options now may be able to control the spread of the disease and have a life expectancy measured in years instead of months.

“In 2024, pelvic exenteration is considered the standard of care for selected patients with locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer,” Dr Brown and his colleagues wrote.

“In patients who choose not to pursue or are not eligible for surgery, stereotactic body radiotherapy combined with systematic chemotherapy, although not curative, may achieve durable disease control for some.”

Pelvic exenteration for rectal cancer is now performed routinely and safely at specialist referral centres, they wrote, with five-year survival rates of 65–75% for primary tumours and 45–53% for recurrent tumours. Pelvic exenteration refers to the removal of reproductive organs and the bladder or rectum, or both.

Cancer Australia and the Cancer Council have published the optimal care pathway for people with colorectal cancer. It includes a checklist and a list of signs, symptoms and results that should be investigated.

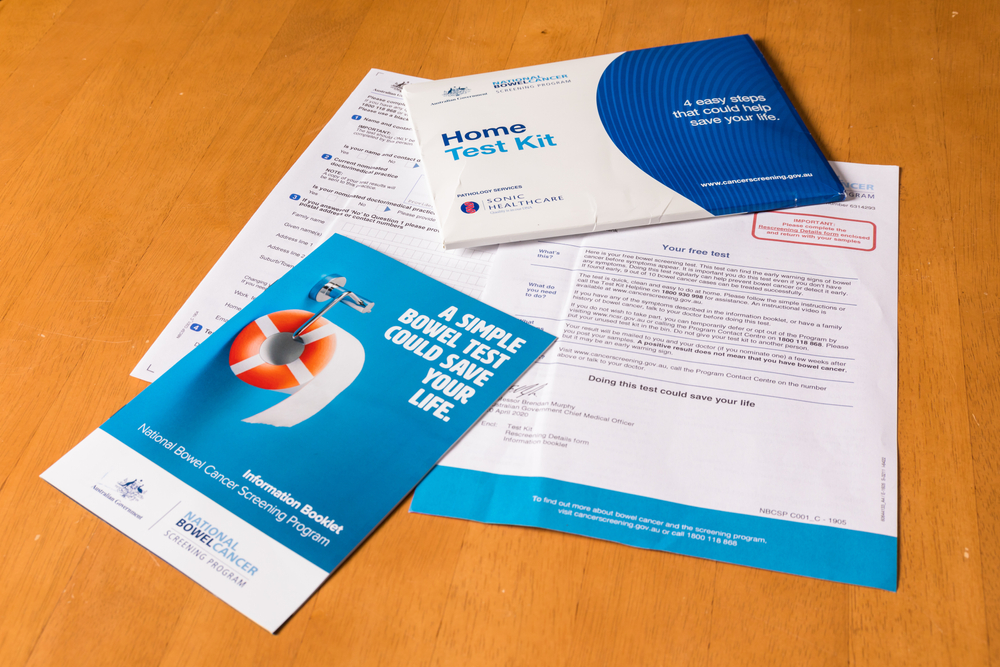

Bowel cancer screening

The benefits of the Australian Government’s National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP) has been strongly defended.

“Bowel cancer screening, the routine testing of asymptomatic people, reduces the morbidity and mortality of bowel cancer by detecting cancer earlier, when the prognosis is better and cancer is more easily treated,” Professor Mark Jenkins and his colleagues wrote in InSight+ recently.

Professor Jenkins is the Director of the Centre of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

“Additionally, because pre-cancerous adenomas are also detected in the course of screening, some bowel cancers can be prevented,” he and his colleagues wrote.

“The NBCSP is a population-based program that mails screening kits every two years to 50–74-year-olds. It unequivocally prevents deaths from bowel cancer.”

Medical practices that do not currently order kits or issue kits are invited to register with the National Cancer Screening Register’s Healthcare Provider Portal. All kits issued to patients must be recorded.

Conversation starters

The Department of Health and Aged Care has published the following conversation starters to help doctors encourage their patients to undertake screening.

- “The bowel screening test is free.”

- “You may feel fit and healthy and have no symptoms, but you can still be at risk of bowel cancer.”

- “The test simple to do at home and could save your life.”

- “If found early, bowel cancer can be successfully treated in more than 90% of cases.”

- “Over the age of 50, the risk of getting bowel cancer increases.”

- “Do it to live a long healthy life and stay healthy for family and friends.”

- “Put the test near the toilet, where you will remember to do it.”

- “The test is clean – this kit includes toilet liners and only the collection tube tip ever touches the poo.”

- “If you don’t want to take one today, we could have the NCSR mail it to your home address.”

Read the Perspective by Dr Brown and colleagues in the Medical Journal of Australia.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

more_vert

more_vert

The focus needs to shift from ”early diagnosis of cancer” to ”prevention of cancer”.

Most neoplasms found at colonoscopy following a positive FOBT are polyps, not cancers, therefore cancer is prevented.

Less confronting to patients and a more positive message for advising screening, in my experience.

The increased risk relates to lifestyle factors and needs at least as much attention as the treatment focus. Government is doing far to little to counteract the massive advertising and consequential ingestion of excess and harmful foodstuffs then leading to obesity, diabetes and mcrobiome changes that appear to be associated with the increased incidence of this costly disease.

The free colo-rectal cancer screening program has been operating in Australia since at least 2006.

I have never qualified for this free program. I expect to live for another 20 years. The uptake by those to whom it is offered is only about 45%.

I agree with Stephen Aldous.

I conclude that the guidelines for access to the program should be widened,

We still hear of patients, young an old, waiting months to get an appointment at a public hospital after a positive FOBT screen, with the actual colonoscopy delayed even further ( the recommendation is no more than 3 months from the time of positive test to colonoscopy. ) This was the inherent weakness in the screening program. There is no point in heavily promoting ( radio, TV etc ) a screening program if we don’t have the facilities to back it up. Some patients , when confronted with the wait times, decide to pay for a private colonoscopy but many can’t do this.

In terms of pelvic exenteration for recurrent rectal cancer, I have a few concerns about this and i am not sure i would have it done myself. It involves an extensive procedure, many months recovery and a resulting colostomy and ileal urinary conduit, hard to manage especially in the elderly. A wise old professor once said ” because a procedure CAN be done doesn’t necessarily mean it SHOULD be done.”

Your “Conversation Starters” include the statement “Over the age of 50, the risk of getting bowel cancer increases.” Why then does the distribution of bowel cancer screening tests cease to anyone over the age of 74, potentially exposing them to risk for a further decade? Presumably the age-associated risks of treatments of the disease also increase