I set out to write a book about miscarriage but ended up researching topics like pollution’s effect on fertility, medical misogyny, abortion culture and feminism and much more. The result is a book that is changing the status quo for women’s health, but it’s only just getting started.

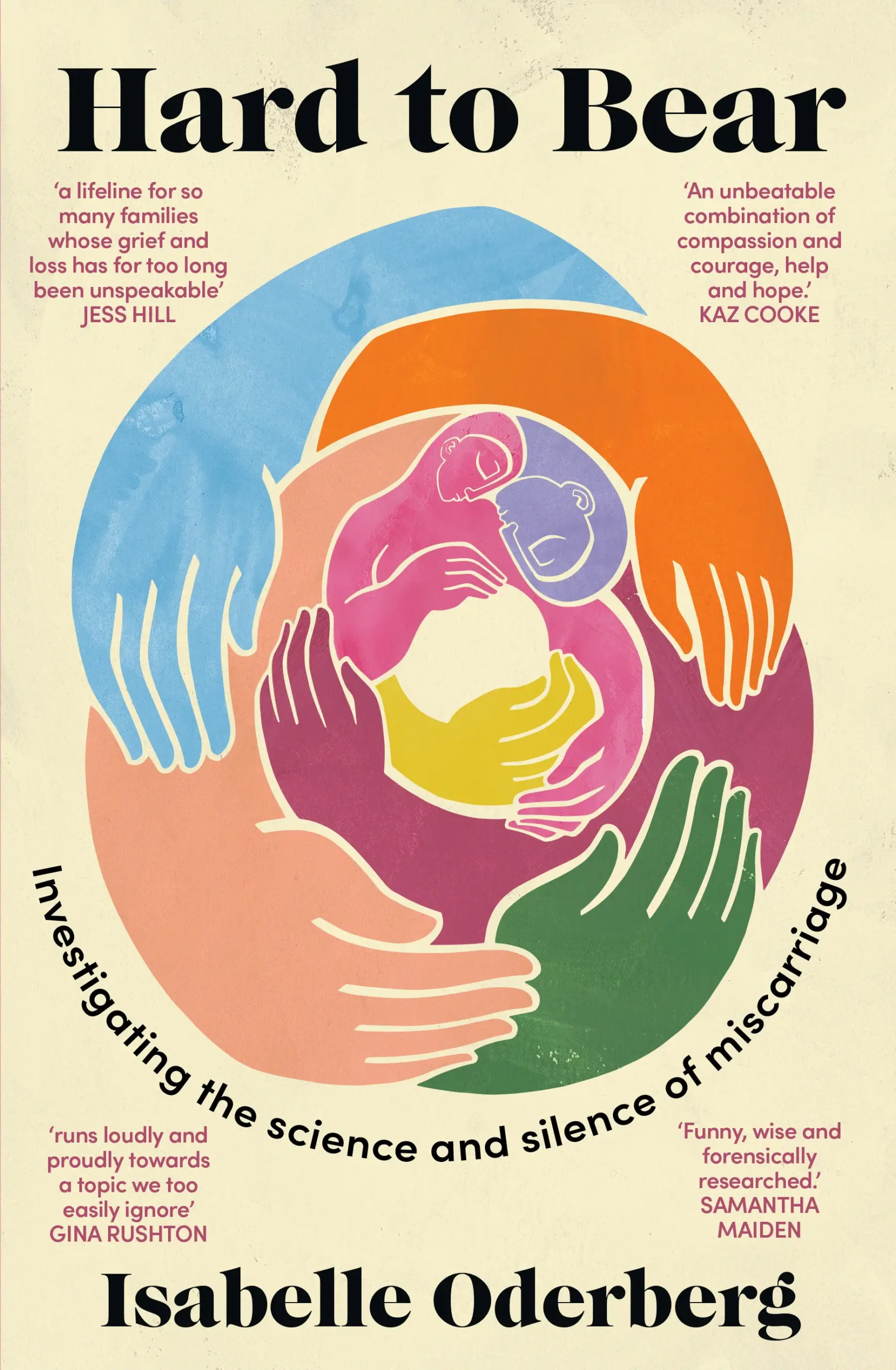

Writing a deep-dive book on miscarriage was always going to be a challenge, but I knew that the most difficult aspect of the task would be completing a work that could benefit a range of readers, not just patients, but also doctors, nurses, policy professionals, activists and more. These groups are central to the change for which my book, Hard to Bear, seeks to be a catalyst.

As someone who has experienced early pregnancy loss many times over, I had a pretty good idea what changes would benefit patients and what they need to know, but to convince doctors, nurses and researchers to pick up the book, ensuring that it was medically thorough and on point was an essential task in terms of reading past page one, but also engendering trust in the many conclusions the book reaches.

I wanted frontline medical staff to read the book and be able to say they had learnt something they might not otherwise have known and walk away from the book with a sense of empowerment and future strategy; understanding that although we have a long way to go in miscarriage understanding and care, there are some straightforward things we can do right now.

In 2018, I was in the midst of my seventh loss. I’d been in Australian and overseas support groups for a number of years, seen a number of different medical professionals and as a working journalist of over two decades, had started reading every piece of research I could get my hands on.

What struck me was the extent to which the topic had been written about in mainstream media — books, column inches, poetry, songs and popular culture storylines — while simultaneously saying so little of substance. In the medical world, miscarriage had been punching well below its weight.

I found myself with more questions than answers … frustrating to say the least. Why is there so little research? Are miscarriage rates going up, down or sideways? Are certain demographic groups more likely to have a miscarriage than others?

In popular culture, the common narrative is “A miscarriage is sad, let’s talk about it more”. These narratives were often driven by grief rather than a genuine desire to impart knowledge beyond the humanity of miscarriage. There was frustratingly little beyond that. Why is it sad? Had it always been sad? Do all cultures recognise it as sad?

Although this book is primarily a journalistic investigation, I never wanted to lose the humanity of the patient and the other people who feel the grief of loss, like partners, grandparents, siblings, even friends and workmates.

I achieved this by allowing the reader a break from the journalistic narrative, through snippets of my own warts-and-all story, punctuated with more than a few laughs. I also interviewed over 100 patients from all over the world, from every demographic you can imagine.

And then there’s the politics. How can a patient be pro-choice but also mourn a pregnancy lost at 10 weeks? Does that make me a hypocrite?

At the same time, my presence in support groups and my many interviews with some of the most renowned health professionals in the world — including Women’s Health Ambassador for England, Dame Professor Lesley Regan and renowned reproductive medicine researcher Professor Arri Coomarasamy, who also heads up Tommy’s National Centre for Miscarriage Research, a partnership between the University of Birmingham, Imperial College London and the University of Warwick — revealed many of the challenges we were facing, especially culturally, were consistent across countries.

Examples include patients not being given their choice of management method for miscarriage (expectant or surgical), doctors using outdated language like “spontaneous abortion” in patient-facing environments, patients not being offered any sort of counselling after loss, patients being seated in waiting areas where heavily pregnant patients are sitting, doctors not recognising or conveying the value of chromosomal testing after loss and a failure to understand how psychosocial support during subsequent pregnancies can improve outcomes.

Why are the same mistakes being made by medical frontline staff all over the world? What are ways we can address these smaller, “bite-sized” issues as a matter of priority, while looking at longer term, structural issues?

The background context for this book was also acknowledgement and constant reminders that the Australian medical system is no longer fit for purpose, and that frontline medical staff are our partners in better care, not a roadblock. Having said that, there certainly are deep-seated fallacies, misunderstandings and biases that I wanted to, and do, challenge.

It seemed ridiculous that miscarriage could be all at once so very common, but also subject to such outdated, even cruel, modes of care. This is not just an ethical or moral position, institutional biases can result in care that falls far short of what could even be considered adequate.

The psychosocial effects of miscarriage can be as traumatic as stillbirth, resulting in some cases in depression or suicidal ideation. Miscarriage is also a risk marker for later health issues such as cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism.

I learnt long ago that no one can demand respect; you earn it. This book represents years of research and guidance from within the sector over four years. I read every medical paper I could get my hands on. With no university affiliations and the related subscriptions, I had to rely on my peers and contacts to provide me with the most up-to-date research and data (I ain’t too proud to beg). I spoke to hundreds of patients, doctors and researchers.

But alongside the patients who read the book and contact me to tell me how empowered and “seen” they feel after reading it, the two most poignant moments since the book’s release were being invited to speak to the Early Pregnancy Loss Network of Victoria (doctors, nurses and midwives who work across the state’s early pregnancy loss clinics) and an extremely moving review in O&G Magazine, produced by the Royal Australian New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

“Hard to Bear empowers, educates, and entertains, and offers countless valuable insights that will help us provide better care,” Dr Kristine Barnden wrote.

I wish I could say “my work here is done”.

It’s not — we have a long way to go.

But I’m proud that Hard to Bear gives such a clear and seemingly respected roadmap for where the future lies and how we can get there.

Isabelle’s career in journalism spans two decades, working for newswires across Europe and Asia, she Australia’s first social media editor at Melbourne’s Herald Sun and her work has appeared in The Age/SMH, Guardian, ABC, Meanjin and elsewhere. Her first book is Hard to Bear: Investigating the science and silence of miscarriage. She is co-founder and chair of the Early Pregnancy Loss Coalition and mother to two living children and seven angel babies.

Hard to Bear: Investigating the science and silence of miscarriage, published by Ultimo, is available online and in all good bookshops.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert