Most Australians die from multiple conditions as shown in new research from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).

Understanding what Australians die from is complex and the answer can vary, if we take into account which health conditions ultimately end a person’s life, the conditions responsible for initiating the death, or what other conditions contributed to the death. The AIHW analysis looks to provide more understanding into why Australians die.

Traditional focus on one, underlying statistic

Traditionally, mortality statistics focus on the underlying (initiating) cause of death. The underlying cause of death is important from a public health perspective to understand where an intervention, if available, could have taken place to prevent the death from occurring.

The underlying cause is vital for understanding the health of a population. The question, “What do Australians die from?” is, however, more complicated than it sounds and can vary depending on what we want to know. Over time, more people are dying with more than one condition (known as multimorbidity) and in 2022, 1 in 5 deaths involved more than five health conditions. Although the analysis of multimorbidity is not a new concept, traditionally the focus has been on selected health conditions and how they are associated, rather than the role each condition plays in a person’s death.

Using all conditions, injuries, and circumstances certified on the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (MCCD) can provide insights into which conditions or injuries lead directly to death, and what other diseases or circumstances contribute to death. It can reveal those conditions that are involved in a death, but may often be less of a focus of public health policy or intervention when only considering the underlying cause of death. It can also indicate the overall impact a disease has on death in Australia. Take for example, coronary heart disease (CHD). CHD is the leading underlying cause of death in Australia in 2022, responsible for 1 in 10 deaths. Yet when we consider those deaths where people died with CHD, not only from it, the number of deaths in total that involved CHD doubles to 1 in 5. Similarly, although diabetes is the underlying cause of death for 3% of deaths (1 in 33), when considering its total involvement in deaths, diabetes in implicated in 1 in 10 deaths of Australians.

Identifying multiple conditions and the roles they play in death

The recent report by the AIHW What do Australians die from? uses all of the information supplied about the conditions, events and circumstances surrounding the death to understand and highlight the role they play in death. Cause of death information certified on the MCCD, as well as additional contextual information identified (where applicable and available) through coronial processes, is coded and collated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This data, housed in the AIHW National Mortality Database, was used to identify which conditions were most commonly involved in the deaths of Australians as an underlying cause of death, a direct cause of death, or a contributory cause of death in 2022.

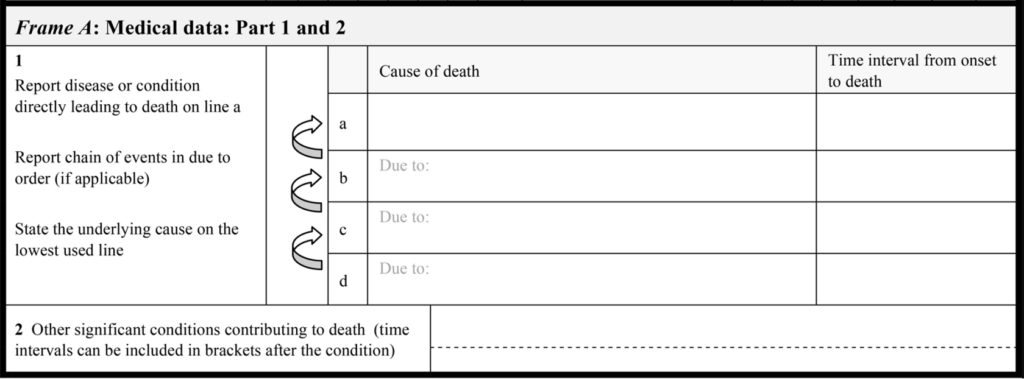

Considering the MCCD (below), the direct causes are conditions, injuries or other health events listed in Part I that were part of the train of events leading to death. The underlying cause of death is the disease, injury or event that initiated that train of events leading to death. The contributory causes are those conditions, circumstances or events listed in Part II as contributing to death, but not part of the chain of events leading directly to death. The video in the report explains these concepts further.

Direct causes of death most often reflect the underlying cause

Direct causes of death (those experienced at the end stages of life) most often reflect disease progression, terminal conditions, and other outcomes of the underlying cause. Younger people (aged 15–44 years) more commonly had injuries and toxicity of substances as direct causes of death, reflecting the leading underlying causes of death in these ages: suicide, road traffic accidents, and accidental poisoning (such as overdose). From the middle to older ages (45–84 years), the leading underlying causes of death shift towards chronic conditions such as CHD, cancer and COVID-19. The most common direct causes of death in these age groups reflect the end-stage conditions and complications of those underlying causes such as infections, cardiorespiratory system or organ failures, sepsis and metastasis.

For those aged over 85 years, dementia was involved in 1 in 5 and CHD in 1 in 3 deaths. Although these conditions were the leading underlying causes of death for people aged 85 years and over, they were also commonly mentioned as contributing to deaths due to other causes. Ill-defined and less specified conditions are more common as age progresses, with “old age” (senility) or “frailty” involved in 1 in 10 deaths of people aged 95 and older.

Common conditions and circumstances contributing to death

Considering the conditions and circumstances that contribute to death from a whole population perspective is often overlooked. Such information can provide additional points for intervention and can provide a better understanding of the impact of diseases and circumstances not highlighted by examining only the underlying cause of death. Overall, chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, CHD and dementia were the most common contributory conditions for deaths in Australia in 2022. The types of conditions that contribute to deaths differ by sex and age, with substance use disorders more common for males, and musculoskeletal conditions more common for females. Substance use disorders and depression were the most common contributors to death for people aged 15 to 54 years.

The availability of information relating to non-medical contextual (psychosocial) circumstances, for coroner certified deaths, adds an additional level of insight into what contributes to death at different ages. Data for 2022 shows that psychosocial factors were most commonly mentioned for external causes of death such as suicide and accidental drug overdose, and the types of factors recorded differed across age groups and between males and females. Issues related to intimate partners (such as arguments, relationship breakdowns) were most common for younger to middle-aged males. Personal history of self-harm was mentioned across all age groups for females and was the most common mentioned psychosocial factor for deaths in those aged 15 to 44 years. Suicide ideation and issues with support systems were mentioned across all age groups for both males and females.

Potential future insights revealed

The report provides a population-level multiple cause perspective for deaths in Australia in 2022. It is anticipated that this analysis highlights the value of integrating multiple cause of death analysis in future monitoring, planning, and prevention activities. Information on the most common direct causes of death, such as infections, can help identify and monitor potentially preventable health events in the chain of events leading to death. Data collated on conditions that significantly contribute to death may help to improve comorbidity management or identify conditions of public health interest (such as hypertension), which, while they may not cause a death, significantly contribute to the death occurring.

What do Australians die from? not only provides insights into the types of conditions causing and contributing to death, but also highlights that much more can be done with the information collected about death. New population-level studies into common co-occurring conditions, or potentially avoidable conditions that contribute to death are possible. Reporting on these public health outcomes can contribute to driving prevention activities, support better policy and service delivery decisions.

Practitioner influence on mortality data

The National Mortality Database is collated from administrative data, and is based on the information certified on the MCCD and coronial process reports. The authors encourage medical practitioners to use best practice guidelines for certifying deaths in Australia. This will ensure the data collected about conditions and circumstances involved in death can provide the most accurate insights for monitoring and improving population health in Australia.

Katrina Sheehan is a data analyst in the Burden of Disease and Mortality Unit at the AIHW. She has almost 10 years’ experience in compiling and analysing Australian death statistics, as well as leading data enhancement projects.

Karen Bishop is a long-serving member of the Burden of Disease and Mortality Unit at the AIHW. She has extensive epidemiology experience, including leading research of mortality in Australia.

Michelle Gourley is the current head of the Burden of Disease and Mortality Unit at the AIHW. She has over 10 years’ experience in providing national leadership on work on burden of disease and mortality in Australia.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Such interesting and important data, thank you for your insights.

2 important matters from my perspective;

– we know (for the most part) what causes mortality in the older ages. I would suggest this doesn’t change significantly from year to year, other than the addition of Covid.

– so following on from the first point, we should have more targeted healthcare and home care for the elderly, but should focus on preventing deaths in younger people (under 55yo). This can be done by much better social services and funding mental health services for adolescents and younger adults which in theory should help prevent substance abuse and suicide. Prevention is always better (and cheaper) and those that do the policy work and hold the budget strings need to recognise and explain their decision making better.

Thank you, great work.

Has an overlay of Indigeneity +/- geography (metro, regional, remote) been attempted on these data?

Interesting read. On thing I wonder – can you die from old age – it seems to me that we medicalise the dying aspects of increasing age and fragility etc.

Thank you for adding new and important details to our understanding of mortality data. Comorbidities/ associated causes are indeed most important, especially in the very elderly. I have just one note of caution, being that the presence of a chronic condition, even some cancers, does not necessarily mean that they contribute to or accelerate the primary fatal condition. (Ca prostate is a prime example). “Dying with” does not always equate to “dying from”. There is also the matter of changes in diagnostic fashions across time, particularly relevant to the “epidemic” of dementias.

As an enthusiastic observer pf mortality data, I would be pleased to discuss further.

With best regards

Yes it’s an interesting process, the recoding of causes of death and unfortunately most medical gradates don’t understand how this works.

When doing my PhD in the UK back in the late 1970s, I requested an historical printout of all causes of female deaths from England and Wales over a longtime, going back to pre WW2. That was happily supplied with me receiving a mountain of paper printout on that lined IBM paper. Going through it I worked out that there were two deaths recorded as being from enuresis – bed wetting. This puzzled me and I contacted the Registrar to get an explanation. That was when it was explained that the cause of death was recorded as the issue that set in motion the chain of events that led to the person’s death. They provided some more detailed information on these two women.

Admitted with bed wetting one was an elderly woman who had fallen, broken her hip in hospital and subsequently died. The other was admitted and while in hospital died from a pulmonary embolus but their enuresis was caused by cancer involving their bladder neck.

This would never happen today. They’d never be admitted.