Dr Will Cairns reflects on a chance childhood meeting with the physicist Leo Szilard, inventor of the atom bomb, and wonders about our capacity to address the challenges facing humankind.

In 1960–61 my family travelled around the world via Hong Kong and England to my father’s sabbatical on Long Island, outside New York City. On the final journey home to Canberra, we stayed for a few days in Los Angeles where Dad wanted to visit the friends and colleagues he had met several years earlier when he spent a few months there on a Fellowship. On the last day of our stopover, before the then five-flight overnight journey across the Pacific, we children were given the choice of a trip to Disneyland or a visit to a relative of the people we were staying with for a morning of swimming in a private pool on a hill somewhere in Pasadena. We chose the latter, and over the course of that leisurely day several visitors dropped by. One of them, who knew of our travels, chatted with my younger brother, then aged about seven. My Dad was greatly amused by the man’s bafflement when Hugh, responding to his question, said that of all the places he had been to around the world, he liked Pasadena best because it was sunny, the swimming was good, and it was nice and near to all his friends in New York.

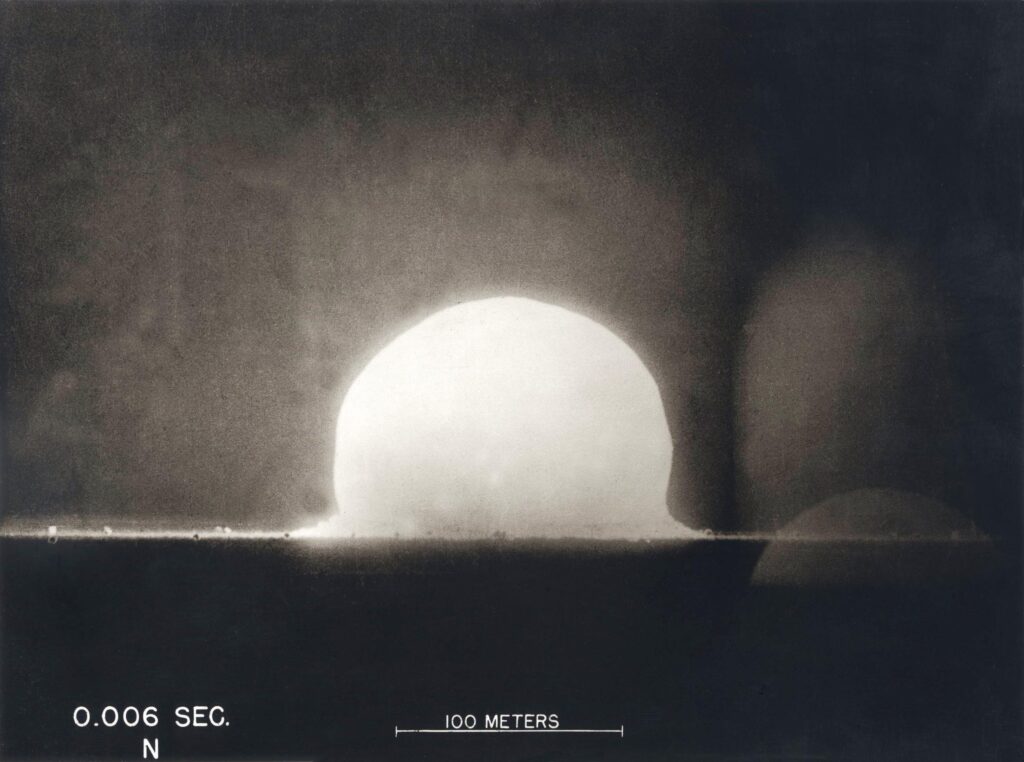

For us as children, the man was just another of the scientists who passed in and out of our lives. We had no idea of his role in history, either then or by the other time we met him again briefly, back in New York in 1963. He was Leo Szilard (1898–1964), the seldom baffled physicist who patented the nuclear reaction, the discovery that led to nuclear power and the atomic bomb. He died the next year.

Anyway, the release of the movie Oppenheimer prompted me to remember those events and to read a biography of Szilard (here). And after I had started to write this article, I discovered Richard Flannagan’s new book, Question 7. In many ways Szilard and his life were far more interesting than Oppenheimer’s, posing questions about the human capacity to deal with complex problems that stretch out over prolonged periods.

Szilard was a Jewish man from Hungary who trained as an engineer, narrowly missed out on dying in the First World War, and eventually studied physics in Berlin. Anticipating the rise of Hitler, he left Germany in the 1930s, eventually settling in the United States.

As a student in Germany, he had not been captivated by the topic he was tasked to study and went off by himself to roam the streets of Berlin while ruminating about a novel approach to understanding the second law of thermodynamics (as you do!). After several months of active thinking, he came back having written an article that for the first time linked entropy and information (I will stop here because I have little understanding of what this means). His mentor Albert Einstein and the other physics luminaries living in Berlin at the time were stunned, and the article was accepted as being sufficient for a PhD.

Szilard loved daydreaming, particularly during many hours in his bathtub. Over time, he created the first patent for an electron microscope, conceived of the nuclear chain reaction (this time from watching a traffic light while wandering the streets of London) and that it could be harnessed for energy or unleashed as a bomb, shared the patent for the first nuclear reactor with Fermi, and realised that it would be possible to use nuclear fission to build a “breeder” reactor that created plutonium.

Although such discoveries may be perceived as negatives, it is important to remember that science is but a series of logical steps and that virtually every discovery or breakthrough made by scientists would soon have been done by someone else when founded on knowledge that is freely available. And that many of the day-to-day benefits of modern technology, including in health care, are derived from the same knowledge that was applied to the creation of the bomb.

Szilard also enjoyed the important scientific pursuit of creating seemingly reasonable hypotheses and then seeking to disprove them. A neighbour told how he once disappeared into his apartment for several weeks. The neighbour could hear baths being run frequently, but did not once see Szilard until he emerged to announce proudly that he had disproved one of his own theories – finding that something is not true narrows the field of contenders for what is true.

Unlike many of his colleagues, Szilard also considered consequences into the more distant future, and sought to do something about it.

Having anticipated the calamity of what was about to happen in Germany in the lead up to the Second World War, he persuaded many, but not all, of his Jewish family and colleagues to leave Europe. After he himself moved to Oxford in England, he helped to set up an organisation that supported several thousand refugees, including many scientists.

Fortunately, it had been Szilard who discovered and patented the nuclear chain reaction because, when he had concurrently realised it could be harnessed as a bomb, he also anticipated that Germany would try to make one, with a very different outcome likely from the war that he also predicted. He then did his best to keep his patent and other subsequent discoveries secret from German scientists, and encouraged his colleagues to do the same. And once the war was underway, it was Szilard who initiated the persuasion of Einstein to send a letter to Roosevelt to encourage the US to build an atomic bomb before Germany did, and drafted the letter himself.

He also understood that once a nuclear bomb was shown to be possible, it would not take long for other nations (particularly Russia) to make one too. From there, by applying what he had learned from observing human behaviour, he foretold the nuclear arms race and the threat of mutual destruction, and that eventually this would lead to the economic necessity for a nuclear arms proliferation treaty, as it did.

Around 1950, he spoke of environmental degradation, recognised the need to limit the human population on a finite planet (including women’s need for effective contraception), and appreciated the issue of environmental degradation and global climate change due to rising carbon dioxide (CO2) levels (CO2 has been known to be a greenhouse gas since 1856).

And, when eventually he developed bladder cancer, he explored what he considered the entirely reasonable option for suicide should he be dying with irremediable suffering. At an autopsy performed after his eventual death from a heart attack, his cancer was found to have been cured by the radiotherapy he advocated for himself.

However, and even as such issues remained important over the years, he struggled to persuade others to engage. He was monitored extensively by the FBI as a potential threat to US national security for wanting to negotiate with Russia about nuclear disarmament, including having met with Khrushchev. Eventually, he was blocked from further work in physics and moved into molecular biology.

So, what is it about most of us that sets Szilard apart?

I understand consciousness as simply being aware of our place in time and space according to the senses that we possess, and that we integrate and apply the information we acquire through those senses to the pursuit of our interests in the present and into the future.

A peregrine falcon spotting a flying bird does not fly to where its prey is now, it learns to predict where it will be in the future and how to meet it there. Even a simple spider can choose the best of a range of complex pathways, including moving out of direct line of sight, to a place where in the future it may be able to capture its prey (O’Hanlon p.22). And many organisms learn to understand the behaviour of their predators, the layout of their local environment, and engage with their community.

As evolved animals, humans are not different – we too observe our world, seek sufficient understanding and explanation, and apply what we have learned for our survival. Our consciousness is not infinite, it is constrained by the scope of our senses, by what we learn from our community, and the capacity of our finite brains.

Szilard showed that rigorous thought can offer rational solutions to complex questions. He was one of those few people whose consciousness extended far beyond the now and the short term. His actions suggest he understood his life as being part of a much larger and complex whole that interacted over long time frames of which others could not conceive. He seemed to recognise that the boundaries of the possible for the persistence of humanity (and life generally) are determined by the laws of physics and chemistry and the physical state of the planet. And he integrated his understanding of the current state with predictions about both human behavioural responses into the longer term future and how the physical world might be changed by human activity.

Unfortunately, our deeply entrenched “human nature” renders most of us incapable of the foresight and wisdom of people such as Szilard. I imagine he came to realise that all too commonly the narrow, and self-interested beliefs of so many members of his community actively obstructed the consideration, comprehension and community action that he had identified as necessary to address complex challenges.

Over just the past few hundred years, our planet and the workings of human society have become increasingly complex and unstable. One might think that, being as smart and aware as we are, we would recognise the peril in the current state of our world, anticipate how it and our fellow humans might behave in the future, seek to understand what we need to do, and respond proactively.

However, while our previously small and relatively predictable world required us to display some flexibility, it also imbued us with a degree of conservatism to constrain us from behaving too erratically. This, and the deeply imbedded pursuit of short term self-interest and parochial tribalism seems to have served us well in simpler times. Unfortunately, it has left us ill-equipped to understand and manage the scale and scope of the long term disruptive consequences of human activity, and for the global cooperation necessary if we are to persist on a destabilised planet.

Recently, conservative politicians have dismissed as a “cult” (and here) the rational scientific analysis of the vast quantities of evidence that describes the burgeoning global climate disaster. Perhaps they were simply mistaking a mirror for a window, or more likely seeking to invert reality in a futile attempt to avoid facing the direct confrontation between growing disruption of our planet and their blinkering human beliefs and attitudes that evolved driven by the context of a world that no longer exists (here).

And now the science that delivers the technology integral to the everyday work of you, the readers of InSight+ who will have to deal with the global health consequences of disruption (see The Lancet, World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and World Bank), is also telling us that there are unpredictable points beyond which it becomes impossible for us to reverse the changes that we have induced (here and here). On a world that can be understood as the workings of physics and chemistry (not to mention the second law of thermodynamics), there is no guarantee that we will be able to generate solutions to the complexity of our current predicament that can re-ravel the growing disorder and restore anything like the prolonged stability of the complex systems within which we became what we are.

As I wrote this article, I was reminded of the metaphor of the monkey trap (here and here) – perhaps we are not so very different from our distant relatives.

So, are we sufficiently wise to address the novel threats generated by our ingenuity and avoid being trapped by how our past shaped us to behave? Or will change simply be imposed on us, as it always has, by the forces that shape evolution by natural selection – disruption, failure and death for those not equipped for whatever the present demands?

Dr Will Cairns has retired from clinical practice as a palliative medicine specialist.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert