Recent research may lead to a misunderstanding about the importance of bowel cancer screening, a vital program which saves 50 Australian lives each week.

We write to defend the importance of the Australian Government’s National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP), following the publication of a recent review shedding doubt on such programs.

JAMA Internal Medicine recently published a systematic review by the University of Oslo of randomised clinical trials of six commonly used cancer screening tests to understand if they prolong life. It concluded that bowel cancer screening using a home test kit might have little effect in saving or extending people’s lives.

The state of bowel cancer in Australia

Before we reposition the findings of that study, let’s look at some statistics.

In 2022, there were an estimated 15 713 new cases of colorectal cancer diagnosed in Australia (8300 men and 7413 women) (here).

This is about 9.7% of all cancers and the fourth most diagnosed cancer. In the same year, there were 5326 deaths from bowel cancer, behind prostate cancer, breast cancer and melanoma of the skin (here). Bowel cancer is consistently among the top ten causes of death in the country.

Surviving bowel cancer is heavily dependent on the stage at diagnosis. For people diagnosed with stage I bowel cancer, the five-year relative survival rate is 99% compared with 13% for those diagnosed at stage IV, when metastatic disease is present (here).

How does screening help?

Bowel cancer screening, the routine testing of asymptomatic people, reduces the morbidity and mortality of bowel cancer by detecting cancer earlier, when the prognosis is better and cancer is more easily treated (here).

Additionally, because pre-cancerous adenomas are also detected in the course of screening, some bowel cancers can be prevented. The NBCSP is a population-based program that mails screening kits every two years to 50–74-year-olds. It unequivocally prevents deaths from bowel cancer (here).

A meta-analysis of three randomised trials demonstrated that stool testing for occult blood, originally using the guaiac faecal occult blood test (gFOBT), reduces deaths from bowel cancer by 23% over a ten-year period for people undergoing screening and by 16% for those invited to screen (here). Since the initial trials, an improved test, the faecal immunochemical test (FIT), has been developed and incorporated into the NBCSP.

Introduced in 2006 and fully implemented since 2019, the NBCSP offers free screening every two years to all people aged 50–74 years using the FIT. An Australian hospital-based, observational study comparing bowel cancer cases detected via the NBCSP with those diagnosed outside any screening reported a superior survival (92% v 70%) and were captured in earlier stages (5.5% v 20.6% in stage IV) (here).

What the recent review gets wrong

The recent JAMA Internal Medicine review paints a misleading picture of bowel cancer screening. It also comes at a time when the NBCSP is focused on increasing the low participation rate (40%) of eligible Australians to improve the program’s reach.

Even at the low participation rate of 40%, modelling suggests that over a 25-year period (2015–2040), the screening program will prevent 59 000 Australian bowel cancer deaths (here). That’s approximately 50 lives every week. If participation is improved to 60%, an additional 24 800 bowel cancer deaths could be prevented (here). We estimate this would save an additional 20 lives per week.

The main problem with the review is that it is based on a false premise: that cancer screening programs should be assessed for effectiveness based on the reduction of all-cause mortality. The majority of deaths, of course, are not caused by bowel cancer (here) and, therefore, cannot be prevented by the early detection and treatment that regular screening enables. There were approximately 190 000 deaths in Australia in 2022 due to hundreds of different causes (here). Only 3% of these (5326) are due to bowel cancer (here). Given these low numbers, the effect of bowel cancer screening on all deaths due to all causes is unlikely to be detectable in clinical trials, as most included studies in the review will be underpowered.

Trials relied on “not relevant”

It is also important to point out that the conditions of the trials upon examined in the JAMA Internal Medicine review are not relevant for evaluating the effectiveness of population screening programs.

The meta-analysis of the traditional gFOBT may not apply to the newer FIT used in most screening programs today, which is more sensitive for bowel cancer (86% v 68%) (here).

Even so, the studies in the review all demonstrate the effectiveness of bowel cancer screening on colorectal cancer mortality, a finding that the authors fail to clearly highlight in their discussion that questions the accuracy of the “screening saves lives” slogan often used to promote bowel cancer screening.

That the review examines only mortality is also a notable deficiency – the benefit of bowel cancer screening on illness, quality of life, and cost of care were not considered.

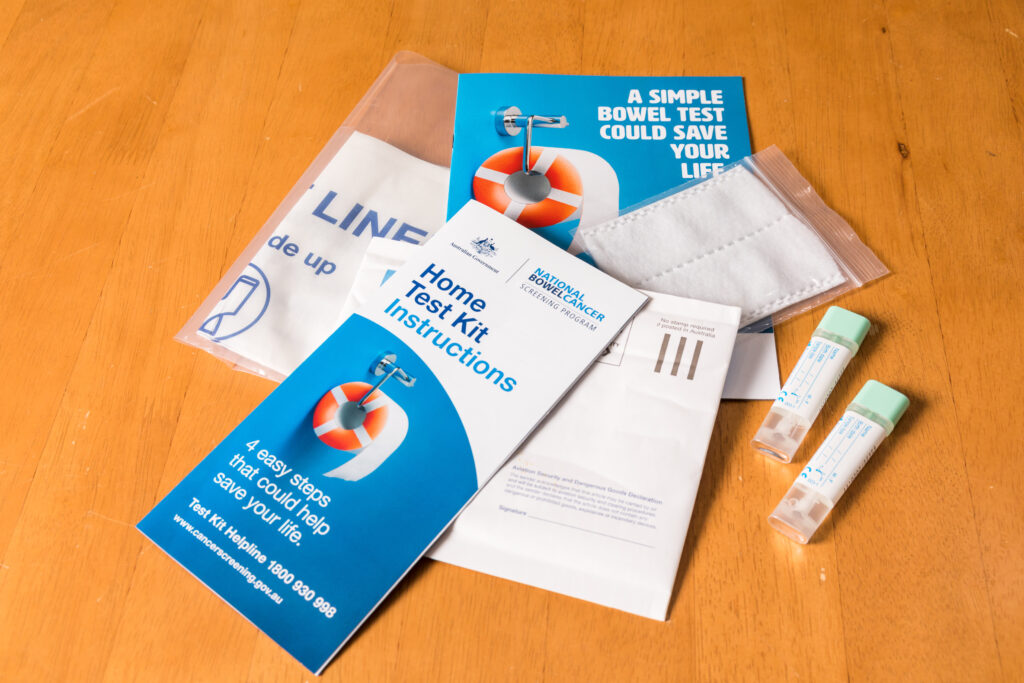

Maintaining confidence in the home test kit

It is vital that the Australian public confidence in the NBCSP home test kit is maintained.

Completing the home test kit can detect cancers early when they are more treatable. This earlier stage diagnosis means, in many cases, that chemotherapy and radiation may be avoided. Additionally, bowel screening reduces the number of people diagnosed with bowel cancer, which can be a devastating and long-lasting illness.

Apprehensions about potential negative outcomes and misconceptions about personal susceptibility act as significant barriers that already deter many Australians from undergoing bowel cancer screening (here).

Articles such as the JAMA Internal Medicine review can erode public confidence further and exacerbate these barriers that behaviour change scientists and health promotion specialists are working so hard to address.

A loss of public faith in the effectiveness of bowel cancer screening could have dire effects on participation rates and hinder our ability to detect and treat bowel cancer early.

Bowel cancer screening is not designed to increase the lifespan for everyone with every disease, but rather to detect bowel cancer early and reduce deaths and the negative impacts of the disease on people affected by it. It is effective in achieving these important and person-centred outcomes. Focusing on all-cause mortality is, at best, a distraction and, at worst, harmful by potentially discouraging participation in the NBCSP.

Professor Mark Jenkins is the Director of the Centre of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

Associate Professor Belinda Goodwin is the Senior Manager of the Health Systems and Behavioural Research Program at Cancer Council Queensland.

Professor Nancy Baxter is the Head of the School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

The authors are investigators of the Bowel Cancer Screening Alliance (BCSA), an Australia-wide multidisciplinary collaboration of leading experts focused on research to increase participation in the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program. The BCSA is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Excellent comments and some aspects of your insights should have been picked up by the peer reviewers of the JAMA Internal Medicine review.

It would also be good to give our Australian program more publicity so that we could reduce the number of people who refuse the free test available.