The importance of culturally appropriate health programs is vital to improving the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, according to a traditional owner from Cape York.

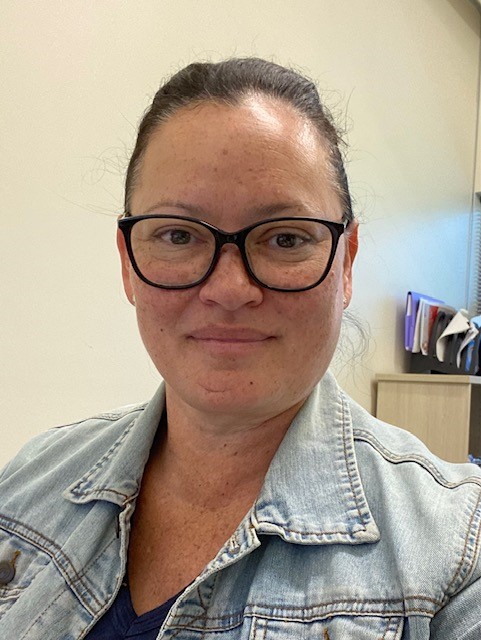

Adjunct Associate Professor Donisha Duff is an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander woman from Thursday Island, and a Yadhaigana and Wuthathi (Cape York) traditional owner.

She spoke exclusively to InSight+ about recent initiatives that have helped improve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing.

Associate Professor Donisha Duff is currently the senior manager of the OCHRe (Our Collaborations in Health Research) Network, and was previously chief operating office at the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health (the Institute) in Southeast Queensland.

Associate Professor Duff has worked for both the Queensland and federal governments including as an Indigenous health advisor to a federal Health Minister.

She has also worked for the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), the Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association (AIDA), and General Practice QLD. Associate Professor Duff is also Board Chair of the Stars Foundation, a school-based engagement and mentoring organisation for girls and women.

The importance of culturally appropriate health programs

Associate Professor Duff told InSight+ that First Nations health care is about First Nations people developing and leading local, culturally appropriate health programs.

“My passion has been the Aboriginal Community Controlled health sector,” Associate Professor Duff said.

“I started at QAIHC (Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council) and at NACCHO, both during and after the implementation of the Close the Gap measures.”

The impact of the pandemic

Associate Professor Duff remembers being on the ground with the Institute when the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began, and how the community health leaders came together.

“It was really strong leadership by the Aboriginal Community Controlled health sector,” Associate Professor Duff said.

“Before the government really knew what it was doing, we identified that our mob were going to be really vulnerable to COVID-19.

“It was about communicating in a culturally appropriate way to our mob about, what is this virus? How can you get it? How can you stay safe?”

One of the key considerations was ensuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people had ongoing access to health services, Associate Professor Duff said.

“We had to change our model of delivery of health care,” Associate Professor Duff said.

“If people are at home, how do we make sure they have access to medications, and can still see a doctor? Particularly our elders and young families living in the same house. How do they keep safe?

“The Institute provides wraparound services for Indigenous people, including GPs, nurses, aged care assessments for elders, NDIS (National Disability Insurance Scheme), allied health – all provided free of charge.”

The service also employs a team of allied health care providers, with all of the available services deployed during the pandemic, Associate Professor Duff said.

“I managed the Deadly Choices program, which is preventative health,” she said.

“We created communications for our mob around social distancing, hygiene, sanitation, access to [rapid antigen] tests. We were packaging up parcels and doing drop-offs. If someone was isolating, we made sure that they had enough food. We did care packs for families with kids and ran a lot of early childhood programs as well.”

It also demonstrated the power of social media, Associate Professor Duff said.

“Because Deadly Choices is focused on fitness and nutrition, we flipped everything online, through Facebook.

“We got football stars like Petero Civoniceva and Steve Renouf from the Brisbane Broncos to do cooking shows, and you could work out with them. On Monday, you can do a yoga session with one of our exercise physiologists. And then do a cooking session, so that your family’s got a meal. It was important that people stayed engaged and active and still were able to communicate with us.”

The Institute launched a new program called Mob Link, a telephone line that mob could call to access health and social services (the number is 1800 254 354).

“It worked from seven to seven, seven days a week,” Associate Professor Duff said.

“So, if anyone had COVID-19 symptoms, we could drop off [rapid antigen] tests and other things. We had a pharmacist as well.”

The Institute worked with Queensland Health and multiple Hospital and Health Services to set up a triage system.

“And we did all of this before we sorted out how we were going to fund it – because it was the right thing to do for our mob,” Associate Professor Duff said.

The importance of mob-led research

In her new role at OCHRe, Associate Professor Duff said, she is promoting the new generation of First Nations health researchers.

“There is a need to focus on developing the next generation of First Nation researchers,” she said.

“We are funded $10 million over five years by the National Health and Medical Research Council. “Over 250 Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander researchers are part of the network, and it’s growing.”

Associate Professor Duff would like Australians to understand that First Nations-controlled health care is a model that works, when they come to vote in the upcoming referendum.

“It’s a simple notion: giving First Nations a say on the issues that impact us,” she said.

“The big gripe you see is about failed programs and millions of dollars and no changes. But at the end of the day, we’re just not being listened to.”

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

more_vert

more_vert