3D printing is already resulting in profound improvements in the quality of life for people with deformities, and it may one day bring significant advances to pharmaceuticals.

Cutting medications in half may be a thing of past, with new research showing pharmacists could use three-dimensional (3D) printing to customise exact dosages to patients.

Researchers at the University of Queensland have investigated the potential of using 3D printing for customise medication dosages.

“For a long time, medicines have been produced with what you might call a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, whereby tablets and capsules come in only a set number of doses. But what if those exact doses don’t work for you?” Research scientist Liam Krueger wrote in The Conversation.

“The traditional solution to these scenarios has been to try and break the tablet into halves or quarters to get a dose in-between.

“But this isn’t possible for every tablet, and even if it is, research shows it often ends up with an inaccurate dose.

“3D printing can take away the guesswork and provide flexibility for health professionals to truly personalise medicine suited to you.”

About 3D printing

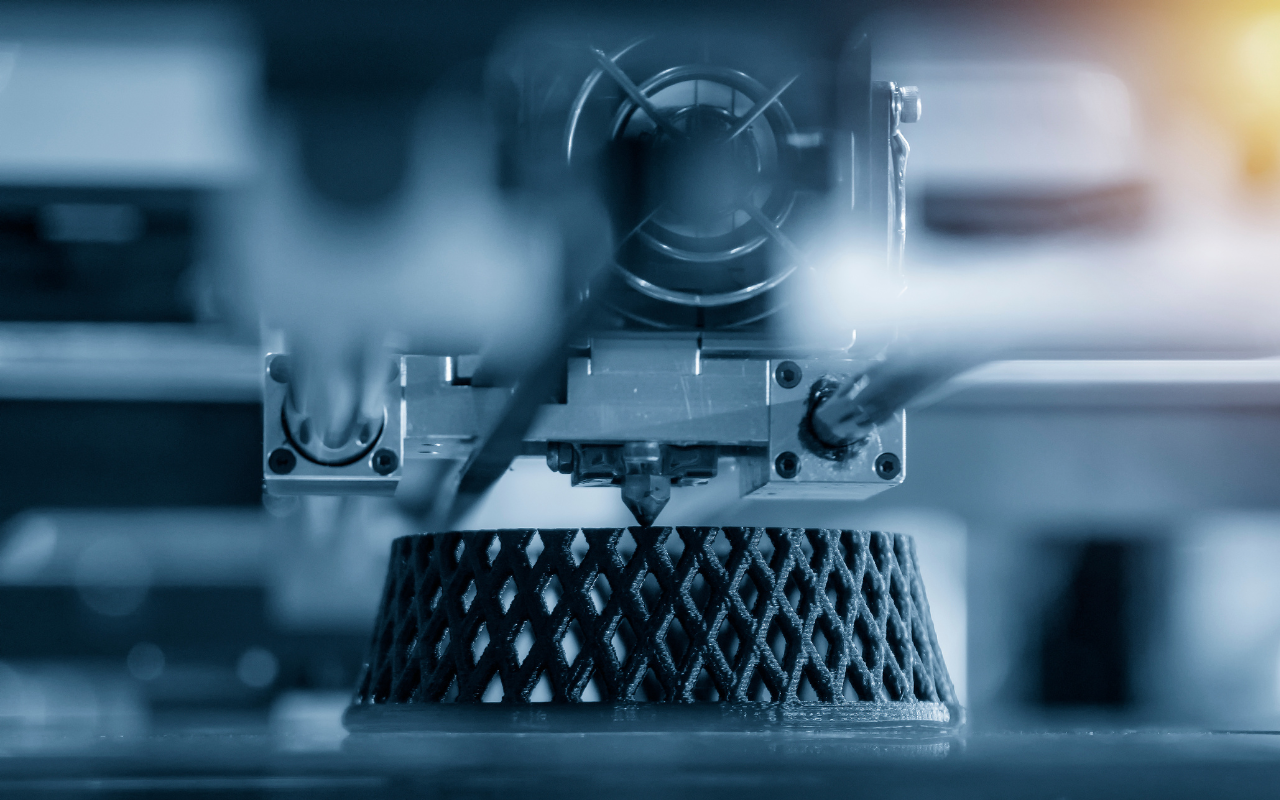

3D printing involves building a 3D object layer by layer with fused materials using a specialised printing device.

It was initially developed for rapid industrial prototyping, but is being increasingly used in the pharmaceutical and health care fields.

A caffeinated experiment

In a proof-of-concept study, the researchers 3D-printed caffeine tablets in dosages of 25 mg, 50 mg and 100 mg using a filament base of polyvinyl alcohol, glycerol and starch.

“While not often thought of as a medicine, the choice of caffeine in this research is important because it is the most widely used behavioural drug worldwide,” wrote Liam Krueger.

“Trying to cut down on caffeine often causes headaches and nausea because of the challenges in lowering the dose correctly.

“This is one of many scenarios where a one-size-fits-all approach would fall short.”

The tablets were successfully printed with drug content within the accepted range of precision, with a relative standard deviation of no more than 3%, and consistent release characteristics greater than 75% in less than 60 minutes.

The results showed far greater accuracy of dosage than that found from physically cutting a conventional caffeine tablet.

“With further research and development, 3D printing could reform the dosing procedures for medications susceptible to severe titration-dependent side effects by providing patients with more accurate and precise dosages tailored to their individual needs,” the study concluded.

Advances in orthopaedics

Even though 3D printing of pharmaceuticals may still have a way to go, the technology is already being used in Australia to reconstruct limbs and correct deformities.

Orthopaedic surgeon Dr Mustafa Alttahir uses 3D printing in limb reconstruction, deformity correction and complex arthroplasty at the Limb Reconstruction Centre at Macquarie University Hospital in Sydney.

“Currently, 3D printing is available in Australia as a technology, but it is still limited to some very bread and butter type of procedures,” Dr Alttahir told The Medical Journal of Australia podcast.

“There’s a lot of 3D printing associated with arthroplasty, for example, that involves hip, knee, ankle and shoulder surgery and that is something that’s been around for a decade.”

“There is now a trend towards more deformity correction and niche type of products in the 3D printing field.

“More orthopaedic surgeons are talking with companies and manufacturers in the process of trying to look at deformities in a more accurate way and utilising 3D modelling, and then using 3D-printed guides to make the surgeries associated with that more accurate.”

At the centre, patients usually have a computed tomography scan done before their consultation and then a team of dedicated engineers use the scan to create a 3D model with specialised computer aided design (CAD) software.

The 3D model can assist in the decision-making process before surgery, and then go on to be used in bone models and implants for the surgery itself.

“As a limb reconstruction centre, we deal with deformities on a very regular basis,” Dr Alttahir said.

“We are in a unique position to utilise this technology on a daily basis because the patients are coming with multilevel deformities and they have problems that benefit from this technology.”

Listen to Dr Alttahir speak about 3D printing on The Medical Journal of Australia podcast.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

more_vert

more_vert

Breaking tablets causing inaccurate doses is of no practicable consequence.