ALL Australian infants who do not pass their newborn hearing screening test should be tested for congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV), a major cause of permanent hearing loss in infants, experts say.

Only a few hospitals across Australia routinely test for congenital CMV after a failed newborn hearing test; however, Western Australian experts writing in the MJA said it was time for a national approach.

“The current approach to the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection across Australia is inadequate,” wrote Reid and colleagues. “Consequently, affected infants regularly fail to receive best practice care.”

They noted that across Australia, the lack of an organised approach to congenital CMV screening resulted in a very low diagnosis rate – less than 2% of cases according to a decade-long study.

Testing could be done with a simple polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of saliva or urine, they wrote. The test has to be done in the first 21 days of life to distinguish between congenital and acquired infection, they added.

“Targeted congenital CMV testing is feasible, cost-effective and enables early intervention,” they wrote, noting their own trial of targeted testing was ongoing.

Although there remained a question mark over whether targeted testing ultimately resulted in better clinical outcomes for the child, the authors said it would be “an improvement on the current approach in Australia”.

Senior co-author, Associate Professor Asha Bowen, clinician researcher at the Perth Children’s Hospital, told InSight+ early diagnosis of congenital CMV was crucial.

“Children who test positive for CMV should get put on a long term follow-up pathway including audiology, ophthalmology and developmental assessments because this is a condition that may progress throughout childhood,” she said.

Associate Professor Bowen said cochlear implants were very effective for children with CMV-related sensorineural hearing loss.

“Picking up a child as young as possible with sensorineural hearing loss and making assessments for a Cochlear implant is a really important step for their speech and language development,” she added.

Antivirals such as ganciclovir and valganciclovir – given in the first 30 days of life – also had a place in the treatment of some patients with congenital CMV, Associate Professor Bowen said.

“Their use is not always routine due to limitations in the evidence base and concerns about potential toxicities,” she said. “Using antivirals comes down to shared decision making between families and clinicians, and tends to be reserved for patients with more significant symptoms.”

Professor Bill Rawlinson, a senior medical virologist and researcher at the UNSW Sydney, has been trying to raise the profile of congenital CMV since he was involved with studies (here and here) showing low awareness of the infection among maternity clinicians and pregnant women.

Professor Rawlinson has worked collaboratively with parents, paediatricians and audiology teams at Sydney Children’s Hospital, where routine testing for congenital CMV of neonates who fail hearing screening has been undertaken for more than a decade.

“It’s important for parents, and the child, to know the cause of the hearing loss. It means we can also follow up for other complications through things such as neurodevelopmental testing and [magnetic resonance imaging],” he told InSight+.

“It also provides evidence of the extent of the problem of CMV.”

Professor Rawlinson said there was strong evidence (here and here) to support not only targeted testing for congenital CMV among infants with conditions such as hearing loss, but also universal screening of all newborns.

“Universal neonatal screening for CMV has some significant benefits over the targeted approach, as it would identify those infants with initially asymptomatic congenital CMV who may develop hearing loss by 5 years of age, but still have normal hearing screening at birth,” he said.

“It would also more definitively show the extent of the problem in Australia, and the effects of any useful interventions such as educational resources for parents.”

The MJA authors also wrote that universal congenital CMV screening warranted consideration, saying it would diagnose almost 2000 infants annually in Australia.

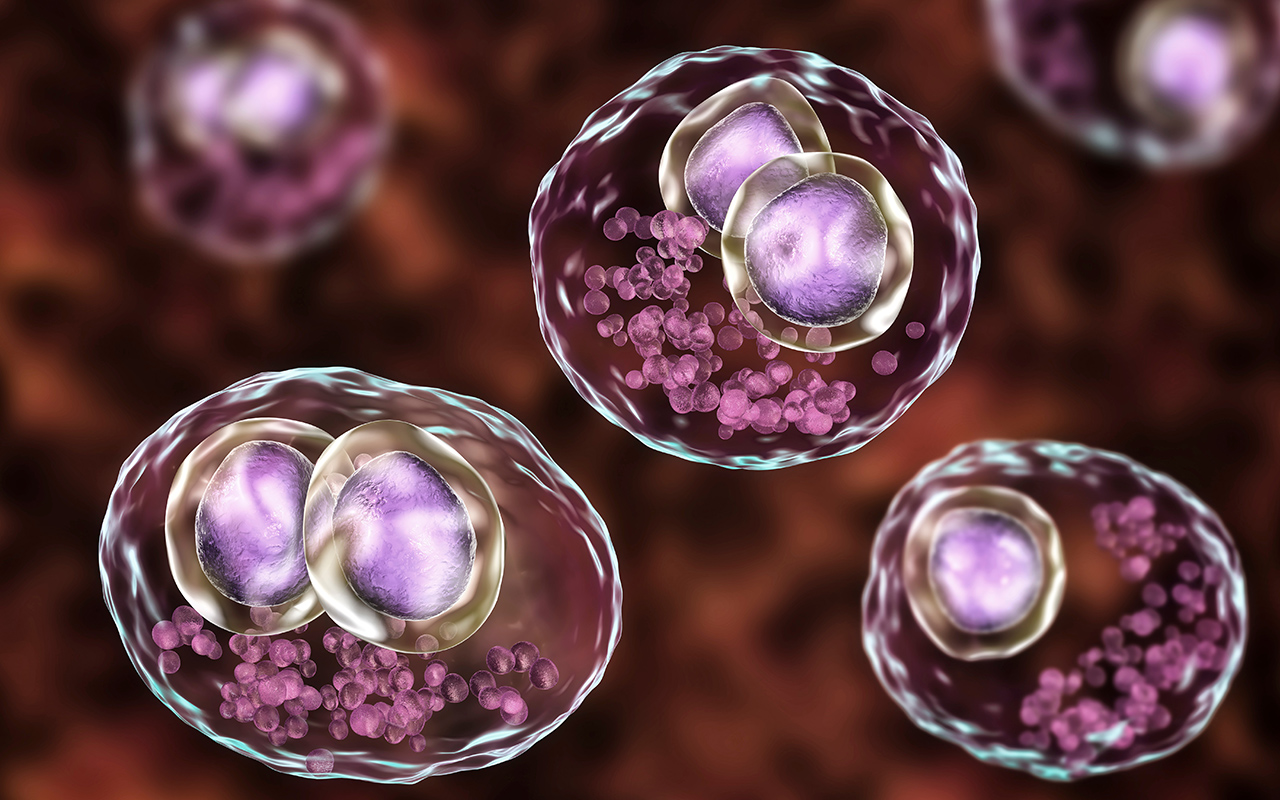

Although 90% of infants infected with congenital CMV remain asymptomatic, the high prevalence of the disease (0.64%) means CMV is a leading cause of congenital malformations in developed countries, affecting more children than better known conditions such as Down syndrome or spina bifida, Reid and colleagues noted.

More than 50% of symptomatic cases have sensorineural hearing loss, including delayed onset up to the age of 6 years. CMV infection is also a known cause of cerebral palsy and in rare cases can cause a life-threatening newborn sepsis-like syndrome, Associate Professor Bowen said.

“CMV is a diagnosis that takes so many families by surprise and that shouldn’t be the case,” Professor Bowen told InSight+. “This is something health professionals really need to be talking with women about before and during pregnancy so they can reduce their risks.”

Official health advice for preventing CMV infection in pregnancy includes not sharing food, drinks and utensils used by young children, avoiding contact with saliva when kissing a child and thoroughly washing hands with soap and water after changing nappies.

The Health Department notes there is an increased risk of infection for seronegative pregnant women who have a young child in the home or who work in childcare centres; however, most pregnant women do not know their CMV status as it is not routinely tested for.

more_vert

more_vert

We have done the studies here and overseas, showing benefits of such testing