AUSTRALIA has insufficient public hospital beds to meet demand and support contemporary clinical practice (here, here and here). Clinicians often struggle with the level of demand, unable to admit patients from emergency departments(EDs) due to inadequate facilities.

Patient access is supressed with historically long surgical waiting lists and ambulance ramping at hospitals across Australia. The COVID-19 pandemic, as the great unwanted audit of acute care, highlights the significance of public hospitals in our communities, the importance of access to acute care and the imperative of supporting clinicians.

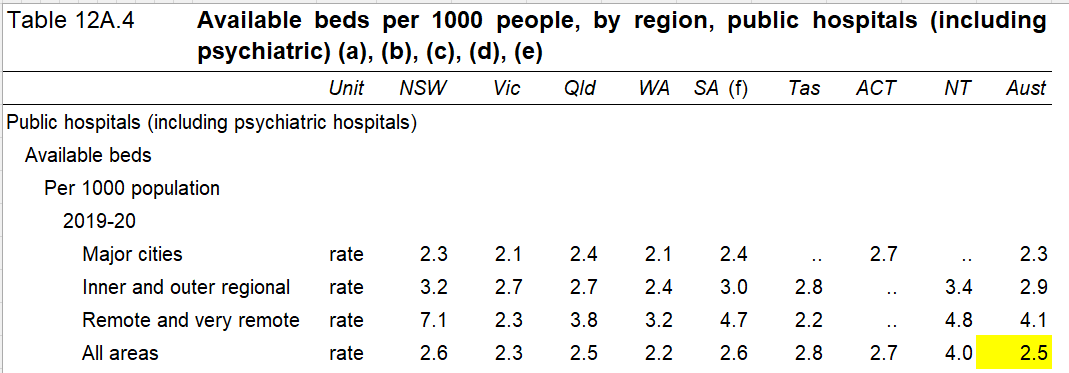

Sustainable clinical practice in Australian public hospitals requires appropriate resourcing. Yet access to beds has decreased to the lowest levels in history, with only 2.5 public hospital beds per 1000 population or half the European and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) ratios.

In my PhD thesis, I showed that investment in public hospitals has fallen below replacement levels for most of this century (Chapter 4). Meanwhile, patient numbers are increasing, medical practice is expanding the range of services offered as new treatments, and new technologies become standards for practice. In areas where access to GPs and specialists is limited, the public hospital is of greater significance to patients.

In a recent InSight+ article, Reddy and colleagues argued that increasing bed numbers is not the answer to growing demand for acute care in 2022. Rather they argued that the financial sustainability of the health system relies on restricting the number of hospital beds and the recurrent costs associated with each bed. Evolving technologies including telehealth, hospital in the home, virtual wards, investment in preventive services and community-based services have been assumed to be sufficient to meet increasing demand for hospital care.

However, despite these innovations in practice, the evidence is that patient demand continues to increase, and the public hospital system has been unable meet the challenges of increasing demand for acute care (here, here and here).

Most state and territory governments have responded by funding ED expansions and/or adding hospital beds (here, here, here, here and here).

Capital funding to increase hospital capacity is a competitive system in most states. Projects to enhance hospital capacity compete with roads, schools and other government priorities in each state and territory budget for funding. Each potential project competes with other projects within health departments for funding. However, operational (or recurrent) funding is allocated for each patient treated, based on patient diagnosis group in shared arrangements between the Commonwealth, states and territories. So, capital funding for improving hospital capacity does not compete with operational funding for any health service.

Australia has a prioritised hospital investment system based on hospital asset replacement, institutional capital planning, budgetary and political priorities. Australian hospital capital allocation systems are not patient-centred or focused on clinical standards. Deeble found the replacement level investment (using 1990s data) would be 7.9% of hospital recurrent costs plus 0.4% for growth. More recently, the Productivity Commission estimated replacement costs for Australian hospitals of 24% of recurrent costs per patient.

What would clinically appropriate capital investment in Australian hospitals cost?

My thesis research on 36% of Australian patients, based on contemporary clinical guidelines, clinical practice and Australian hospital standards, found that the investment requirements per patient were between 5% and 36% of operating costs, varying by diagnosis group (Table 8.19 page 205). Hip replacement of major complexity had the lowest capital to recurrent cost ratio (5%), and a birth of minor complexity had higher capital to recurrent ratio (36%) due to lower operational costs (Table 8.19).

I found that operational cost efficiency could be achieved by following clinical standards and investing in required equipment and facilities (page 189). Investment in facilities and equipment required for newer modes of practice was found to provide good quality outcomes, including reducing length of stay, demand for intensive care unit beds and decreasing staff costs.

Sustainable hospitals

Recruiting and retaining medical and nursing staff have greater importance since the COVID-19 pandemic, as staff shortages and burnout have been evident (here, here and here). Part of the answer will involve investment in sufficient clinically supportive and appropriate facilities, beds, information and communications technology, systems and equipment. Enhanced staff areas, education and break spaces, including outdoor areas, may also be needed to attract and retain staff investment.

Patient and staff safety in hospitals during infectious diseases outbreaks may require physical modifications to hospitals for EDs, in waiting rooms, reducing the number of shared wards, improving air circulation, and improving access to beds, including intensive care beds.

Climate change is expected to increase the demand for care in hospitals associated with heatwaves, infectious diseases, floods and fires (here and here). Awareness of these threats of extreme events means a level of preparedness will also need to be built into hospital facilities.

Medical research delivers new diagnostic and treatment options while communications and information technologies enable safer care (here and here). To deliver a constantly improving clinical environment there is a need for reliable, continuous capital funding for public hospitals to support continuous improvement (here and here). A health system that responds to patient demand, incorporates clinical improvements and can actively implement the lessons of best practice COVID-19 management can be resilient.

Continuous improvement

The COVID-19 pandemic has affirmed that Australians expect the promise of Medicare to be fulfilled. This means patients requiring acute care must have access to appropriate clinical care in effective hospitals. In my thesis, I showed that whole-of-hospital investment, based on clinical standards and clinical pathways, is the strongest method for every Australian hospital to achieve these objectives.

In Europe, systems with sufficient capacity were better able to adapt during the pandemic. A system that invests in contemporary standards of care with capacity to manage reasonably foreseeable problems may prove more useful than the existing asset replacement system for hospitals.

I believe a clinically guided diagnosis-based system for capital allocation for public hospitals has been identified as the most efficient way to deliver universal access to effective and efficient care for patients (here and here). In my opinion, the existing system has not funded patients’ access to effective hospitals at the standards expected by Australians. It has not supported clinicians meeting clinical standards during high levels of demand.

A system that gives preference to reducing hospital investment and beds, as suggested by Reddy and colleagues, is unlikely to be responsive to the changes Australian clinicians and hospitals will face in coming years.

Australia has a well established system of activity-based funding. However, the national funding system for operational costs has no capital funding component. The lack of a capital funding component for hospitals has meant the number of beds, diagnostic and treatment spaces have failed to keep pace with the demand from patients of the public hospital system. Across Australia, the absence of appropriate and reliable capital investment has failed to deliver capacity growth to match patient demand and clinical improvements.

As Australian hospitals face a range of new challenges, it is an appropriate time for a national non-political system of capital funding for continuous improvement of all Australian public hospitals. The strongest option, I believe, is to provide capital funding per patient, based on diagnosis group in a system aligned with the existing activity-based funding for hospitals. Commonwealth–state shared funding for the capital is required to deliver equitable and clinically appropriate care in each Australian hospital to prepare for future patients.

Dr Rhonda Kerr researches hospital efficiency, public finance and health economics. Her doctoral research at Curtin University has evaluated capital funding systems in 18 OECD countries for efficiency, fiscal sustainability, delivery of clinical standards, and responsiveness to clinical improvements and patient demand. Her current project is to fund hospitals to improve patient access to clinically effective, sustainable, and technologically relevant care while improving hospital efficiency.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Surprisingly you make no mention at all of the private system. Analysis by the Commonwealth Fund shows the UK NHS has the worst patient outcomes of all the major countries they assessed. Reviews by the Netherlands and Singapore both concluded that a carefully regulated private system with a government funded safety net is the best approach.