STROKE remains the second most common cause of death worldwide and a major cause of disability. In about a third of cases, the harbinger of major stroke is a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or minor stroke with a little residual deficit.

As such, these events represent a unique opportunity to intervene and put in place long term prevention strategies to reduce the likelihood of further events and subsequent death and disability. Over the past 40 years or so, there have been enormous advances in proven and highly effective interventions in primary and secondary stroke prevention.

For example, randomised controlled trial evidence now exists for fatal and non-fatal stroke risk reduction with blood pressure and cholesterol lowering, the use of antiplatelet agents, novel anticoagulants for patient in atrial fibrillation, as well as carotid endarterectomy and stenting. Even though this suite of interventions may reassure us that we now have the issue under control, the question as to whether these interventions are effective in a real-world environment remains.

It was to this end that the TIAregistry.org was established in 2009 by Amarenco and colleagues as the largest cohort of its type, with recruitment of 3847 patients from 42 centres in 21 countries across the globe. The registry was populated from TIA clinics and stroke units, usually associated with tertiary teaching hospitals where the level of expertise for secondary prevention was quite high.

The advantages of a cohort such as this are the large sample size, the global nature of the accrual process and the real-world environment of the study. The main shortcoming is that the findings may not be generalisable to less expert clinical settings. Nevertheless, any findings of lack of effectiveness of secondary prevention strategies are more likely to be exaggerated elsewhere.

There have now been a series of reports from the TIAregistry.org group of outcomes including one year and 5 years after the event onset (here and here). In this most recent report, the factors influencing disability at 5 years are examined in detail so that even more effective prevention strategies may be adopted.

The findings were extremely important.

Disability at 5 years was significant and worse than expected among the general community. Importantly, modifiable risk factors were found which contributed to this disability.

The two most important that are worth commenting upon were the presence of any type of diabetes and a history of having undertaken significant exercise before the event. Remarkably, a history of having undertaken regular exercise reduced the risk of disabling stroke by almost half. Also, and quite logically, recurrent TIA or stroke events were significant contributors to long term disability.

Given that the recurrent theme of all reports from TIAregistry.org has been that stroke recurrence continues in spite of the application of recently effective prevention strategies, what is the role of Australian GPs in this scenario?

First, as mentioned earlier, a TIA or minor stroke event represents a real opportunity to intervene. In most cases, this is ultimately going to fall upon the shoulders of the general practice community.

Second, the control of modifiable risk factors needs to be lifted to the new level of excellence. This is a particular challenge since, as mentioned earlier, stroke recurrence and disability occurred to unacceptable levels, even when patients are managed in the more sophisticated setting of tertiary hospital TIA clinics and stroke units. One way to assist in this task is to have ready access to easily understood clinical guidelines based on up-to-date and relevant information.

It is worth noting that, in Australia, we are in the fortunate position of having the world’s first “living stroke guidelines’’ to help in this endeavour. This unique repository of information is housed on the Stroke Foundation website and is responsive within a period of months, and at the MJA, to any new clinical information that is likely to alter the current guidelines. Other countries usually publish guidelines, or sections thereof, episodically and often many years later.

Some examples of the guidelines for secondary stroke prevention include keeping tight glycaemic control and consequent glycated haemoglobin levels of under 7%, routine administration of suggested blood pressure-lowering agents that are initiated or intensified when clinic blood pressure is > 140/90 mmHg, cholesterol lowering with a treat to target of low-density lipoprotein 1.8 mmol/L, the long term use of dual antiplatelet agents early after the onset of TIA or minor ischaemic stroke, and long term use of antiplatelet monotherapy, either aspirin or clopidogrel.

Direct anticoagulants (DOACS) that do not require regular blood tests to monitor anticoagulant levels have largely replaced warfarin and have revolutionised stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. In Australia, the main DOACS in use include apixaban, rivaroxaban and dabigatran.

The finding from the current study that a prior habit of regular exercise is also worth noting, particularly given the magnitude of the effect mentioned earlier and the known benefits of exercise in the prevention of a variety of non-communicable diseases such as dementia.

Although our performance in stroke prevention has not been perfect to date, the fact that modifiable risk factors have been identified to improve long term disability can give us some optimism about the future.

If the rate of discovery of new interventions for both primary and secondary stroke prevention is replicated over the next 40 years, more sophisticated approaches to reduction of stroke recurrence and disability are even more likely. Hence, Australia’s GPs, hopefully much better resourced, will have even more effective tools at their disposal. They will also be assisted by an increasingly nimble, accessible and practical clinical stroke guidelines system.

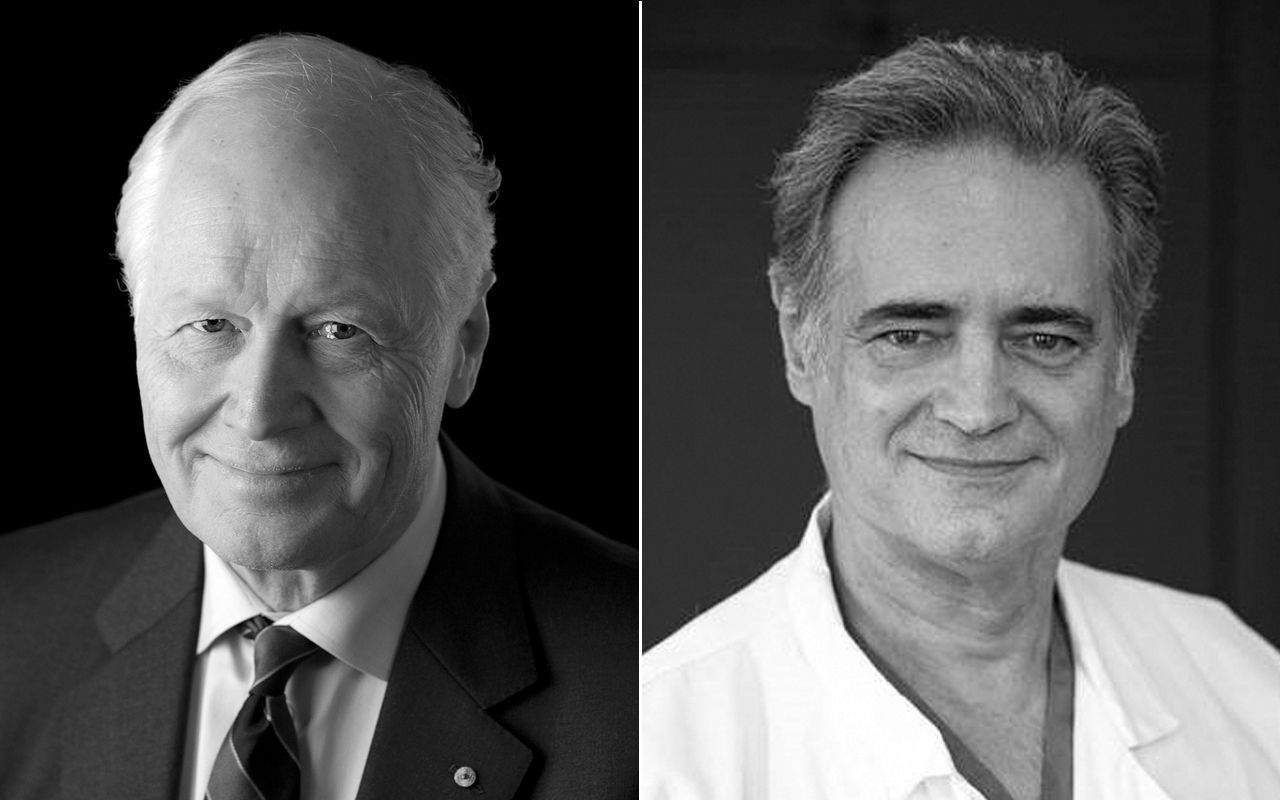

Professor Geoffrey Donnan AO is a neurologist, Professor of Neurology at the University of Melbourne and co-Chair of the Australian Stroke Alliance. He is with the Melbourne Brain Centre at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Professor Pierre Amarenco is Professor of Neurology at Paris University, and Chair and Founder of the Department of Neurology and Stroke Centre at Bichat Hospital in Paris.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Corporate item number mining- computer programs identifying patients “eligible” rather than needing high paying items needs to be looked at.