THE implications of increasingly extreme fluctuations in Australia’s climate (and in that of the rest of the world), on the risk of acute coronary events and resultant demand for acute cardiac services, require urgent exploration.

Particular attention should be placed on extreme weather events in summer, when high temperatures may be combined with increased air pollution and, all too often, the occurrence of wildfires. Australians are no strangers to this combination, but the summer of 2019–20 was particularly problematic, with record temperatures complicated by extensive bushfires in the eastern states and South Australia. Not surprisingly, there were individual reports of collapse, and sometimes of deaths, among individuals fighting fires.

Previous publications suggest that chronically elevated temperatures and persistently increased air pollution represent coronary risk factors, and that increased ambient fine particle pollution (of the order of 2.5 µm or smaller [PM2.5]) is particularly dangerous. However, far less information is available regarding the impact of rapid changes of these circumstances, particularly in association with bushfires.

My colleagues and I therefore chose to use hospital admission data from Adelaide to evaluate the individual and combined impacts of elevated temperature, atmospheric density of PM2.5, and presence of active bushfires within 200 km on the frequency of hospital presentation with acute coronary syndromes (ACS; eg, acute myocardial infarctions [AMI] or unstable angina pectoris [UAP]) over a 120-day period from November 2019 to the end of February 2020. Data on hospital admissions from all the adult public tertiary hospitals in the Adelaide metropolitan area were categorised in this manner.

Given that Takotsubo syndrome (TTS; ie, stress cardiomyopathy or “broken heart syndrome”) may theoretically be precipitated by acute stressful events, especially in older women, we also evaluated potential associations between these same environmental factors and the incidence of TTS. Once thought to be rare, methodology for TSS differentiation from AMI has improved substantially in the past 10 years and is now known to account for about 10% of suspected ACS cases in women.

Data on 539 patients were available — 402 had AMI and 92 had UAP. Most of the patients were older (mean age 69 years) and the majority of patients with AMI or UAP were men. A further ten patients had presumptive AMI without haemodynamically significant coronary artery stenoses. On the other hand, only 35 patients were diagnosed with TTS, 89% of these were women. A total of 25 patients died in hospital.

Bushfires were present within 200 km of Adelaide on 47 of the 120 days evaluated. Atmospheric PM2.5 concentrations were generally low, exceeding “safe” limits (25 µg/m3) on only 14 days.

Data analyses for patients with AMI or UAP showed that elevation of temperatures was strongly predictive of the number of daily presentations, as was elevation of PM2.5 concentrations beyond “safe” limits. As a univariate parameter, presence of bushfires was associated only with a non-significant trend towards increases in AMI and UAP incidence.

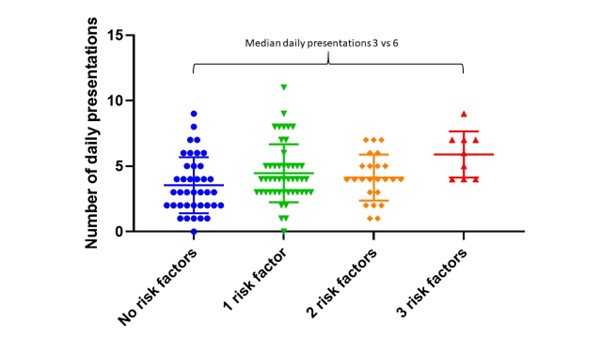

On days when all three of these risk factors occurred together, there was an incremental impact on AMI and UAP risk. Thus, when all three risk factors were present, there was an approximate doubling of AMI and UAP incidence (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The impact of all 3 factors individually, and in combination on number of daily presentations. Reproduced with permission.

Regarding TTS, we found no significant variability in incidence according to the presence or absence of any of the AMI and UAP risk factors. It is possible that this reflected the relatively small number of patients with TTS studied.

Our study had a number of limitations beyond the small number of patients with TTS. For example, we had no individual data as to how close any of the patients evaluated had actually come to the bushfires, nor what was the concentration of PM2.5 particles in the atmosphere in the precise region where they lived. We had no available data on which of the patients studied had pre-existing coronary disease. We were unable to determine whether “hysteresis” (a lag phase between risk factor exposure and onset of symptoms) might apply because none of the factors evaluated fluctuated substantially from day to day.

Finally, our results might have been different if we had been considering a region where year-round levels of air pollution are higher than those in Adelaide.

Despite these limitations, it can be concluded from our results that elevation of ambient temperature, presence of increased atmospheric PM2.5 concentrations, and proximity of bushfires should be regarded, especially cumulatively, as predictors of increased frequency of presentation to hospital emergency departments with AMI and UAP. Although not yet studied in the same manner, similar considerations may well apply to respiratory emergencies.

Possible public health implications of these findings are that efforts should be made to maximise availability of beds in emergency departments on what might now be regarded as “high ACS risk” days. Furthermore, the public, especially the elderly, should be made aware of this incremental risk.

John Horowitz is Emeritus Professor of Cardiology at the Basil Hetzel Institute University of Adelaide.

Gao Jing Ong, Cardiology Research Laboratory, Basil Hetzel Institute for Translational Health Research, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Alexander Sellers, Cardiology Department, Central Adelaide Local Health Network, Adelaide.

Gnanadevan Mahadavan, Cardiology Department, Central Adelaide Local Health Network, Adelaide.

Thanh H Nguyen, Cardiology Research Laboratory, Basil Hetzel Institute for Translational Health Research, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Adelaide.

Matthew I Worthley, University of Adelaide.

Derek P Chew, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

It would be interesting to look at the experience of bushfire brigade members. A shift of bushfire fighting may last 12 hours, with intense smoke exposure much of that time.