AS COVID-19 restrictions continue to be rolled back, influenza may not be the only infectious disease which sees a resurgence this winter.

Experts say influenza’s well documented correlation with invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) may give a clue to what is to come, with the UK already experiencing rises in meningitis B cases among students over winter.

A 2020 study established a strong correlation between influenza incidence and that of IMD, with the authors reporting: “We found that surges in influenza activity result in an acute increase in population-level IMD risk”.

“This effect is seen across diverse geographic regions in North America, France and Australia. The impact of influenza infection on downstream meningococcal risk should be considered a potential benefit of influenza immunisation programs.”

Now Australian experts, writing in the MJA, say it is no coincidence that influenza and IMD case numbers were “the lowest since records began” in 2020 and 2021 as public health policies and restrictions introduced to slow the spread of COVID-19 were enforced.

“In January 2020, there were 12 cases of IMD in Australia,” Dr Robert George, Deputy Director of Microbiology at NSW Health Pathology at John Hunter Hospital in Newcastle and a co-author of the MJA article, told InSight+ in an exclusive podcast to be published on Wednesday 30 March.

“In February 2020, there were 13 cases. And then in March 2020 [when COVID-19 restrictions came into force], there were six cases.

“The remaining 9 months for 2020 had, on average, less than 7 cases of IMD per month. That’s substantially lower than for example, in 2017, when there were 72 cases for that same period. In 2018, there were 52 cases, and in 2019, there were 38 cases.”

Influenza, SARS-CoV-2 infection and IMD have several things in common, Dr George said.

“They’re vaccine preventable, they have seasonal prevalence patterns, they’re transmitted by respiratory routes, and contact and droplet transmission is particularly important.”

Where they differ is crucial to the documented interplay between influenza and IMD.

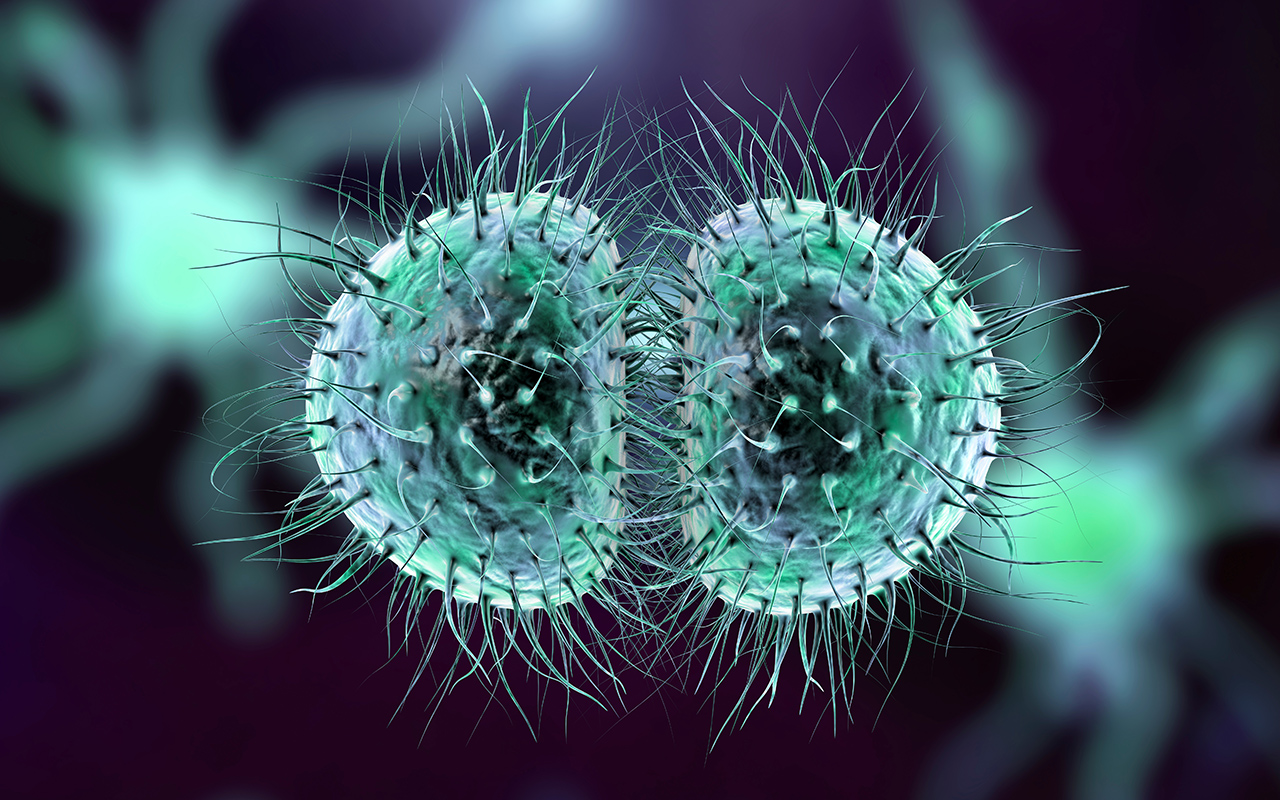

“The nasopharyngeal epithelial injury associated with influenza infection … may permit colonist Neisseria meningitidis [the bacterium that causes IMD] to invade and cause disease,” George and colleagues wrote in the MJA.

Given the effectiveness of social distancing, mask wearing and hand-washing in combatting the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, it should come as no surprise to see other infectious diseases become less common, as well.

“The impact of measures aiming to limit crowding which have prevented person-to-person transmission of COVID-19 have also appeared to impact a vast array of other infections,” Dr George told InSight+.

“For example, pertussis – there were around 560 cases of pertussis in 2021, which is substantially lower than the 5-year rolling average from 2016, which exceeded 12 000.

“Similarly, there have been declines in invasive pneumococcal disease. In Australia in 2021, numbers were around 1300, again lower than that 1800 rolling 5-year average.

“We’ve also seen declines in chickenpox being caused by varicella zoster, measles, and rubella.”

So what can we expect for IMD now that restrictions and public health policies are being lifted around the country? Has the general public learned lessons about infection control?

Professor Monica Lahra, Medical Director, NSW Health Pathology, Microbiology at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney, and senior author of the MJA paper, told InSight+ that it was “difficult to say”.

“Raising awareness of infection control among the public has been a critical part of pandemic management,” she said. “But [COVID-19] was a novel situation. We don’t know what will happen going forwards [in terms of continued public awareness].”

In their MJA article, George and colleagues wrote that recent findings demonstrate “that reductions in case numbers can be achieved in a broader social context and on a far greater scale”.

“While the combination of factors that have driven IMD and influenza in Australia to their lowest levels on record in 2020 and 2021 may not continue to conspire, the public health lessons will hopefully not be forgotten,” they concluded.

Meanwhile GPs and emergency room physicians will likely be the first to see presentations that may suggest IMD.

Professor Robert Booy, co-author, and paediatrician and Professorial Fellow at the University of Sydney, noted that:

“Parents should watch for a high fever and symptoms like irritability, headache or drowsiness. Some have gastro symptoms (vomiting, diarrhoea), or a pin prick purple rash.”

NSW Health’s meningococcal disease fact sheet notes: “People with meningococcal disease can become extremely unwell very quickly. Five to ten per cent of patients with meningococcal disease die, even despite rapid treatment.”

Professor Lahra added: “A heightened level of suspicion [for IMD] is very important, particularly as we move into the winter months.”

Also online first at mja.com.au today:

Research: Detecting primary aldosteronism in Australian primary care: a prospective study

Libianto et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51438 … FREE ACCESS permanently.

Research: Achieving lipid targets within 12 months of an acute coronary syndrome: an observational analysis

Alsadat et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.51442 … FREE ACCESS permanently.

more_vert

more_vert