A SURVEY of Australian infectious diseases (and related) clinicians has found that 51% supported “elimination”, while 41% supported “control” to counter COVID-19. Victorian respondents were less confident in their state’s capacity to suppress further outbreaks than respondents from other states. Trainees were least confident in the health care system’s ability to limit health care worker infections.

In developing a public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic, nations have a choice between three recognised epidemiological strategies.

- Mitigation, shielding vulnerable populations while limiting social and economic disruption, has been adopted in Sweden, but rejected by most developed nations due to its higher associated mortality.

- Control, the reduction of disease incidence to a locally acceptable level, has been adopted by most developed nations with varying success.

- Elimination, which aims for zero incidence within a defined geographic area, has been pursued by some island nations such as New Zealand.

Australia’s public health response of aggressive suppression was initially highly successful. More recently, as Victoria has grappled with its second wave, there has been debate about the best public health strategy to pursue. Some jurisdictions have achieved elimination, while others pursue a strategy of control. Closed state borders have been used to defend local elimination, resulting in significant economic and social disruption.

High levels of health care worker (HCW) infections have been a disturbing feature of this pandemic. Notably in Victoria’s second wave, HCWs represented a high proportion of infections, comprising approximately 15% of active infections (at 12 September).

We performed a voluntary anonymous survey to establish the views of the Australian infectious diseases community on which public health strategy they supported and their confidence in public health systems to counter COVID-19. The survey was preceded by referenced definitions of the epidemiological concepts with application to our local setting. “Aggressive suppression” was defined as a control strategy, as conceptualised by those who devised the strategy.

Ethics approval was waived by Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee. The survey, open between Tuesday 1 and Friday 11 September 2020, was distributed through an established email forum of Australian and New Zealand infectious diseases (and related specialty) clinicians; approximately 600 were eligible to complete the survey.

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS statistical software package version 27 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Categorial variables were compared using Χ2 test and results were considered to be statistically significant if P < 0.05.

There were 200 respondents, with 86 from Victoria, 45 from New South Wales and 69 from the remaining states and territories; 39 respondents were advanced trainees, 78 were specialists with less than 10 years since qualification and 83 with more than 10 years. The majority (81.5%) were infectious diseases specialists, with microbiologists (15.5%) and those who work in public health or epidemiology (3.0%) also involved.

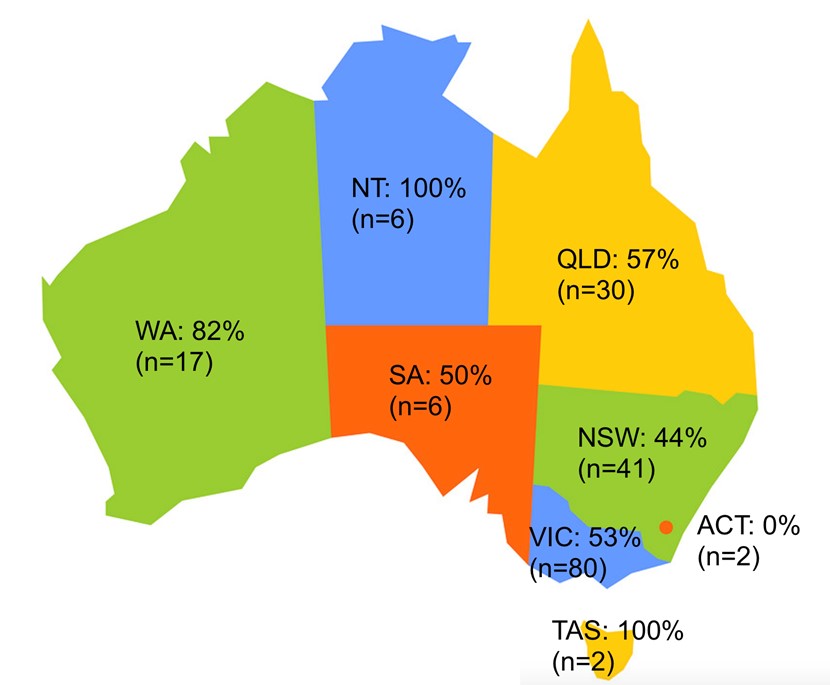

Most respondents (51%) supported elimination, but the survey revealed that among infectious diseases (and related) specialists, there was a divergence of views on the best public health strategy to combat COVID-19, with 41% supporting control. The remaining 8% did not have a clear view. A majority of clinicians favoured elimination in all jurisdictions (aside from South Australia, where opinion was split, and New South Wales, where control was favoured), although sample size was limited outside of eastern seaboard states (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Map of Australia with proportion of surveyed specialists favouring elimination. Participants who chose “Don’t have a clear view” were excluded from this infographic.

Fifty-three percent of respondents would not support a strategy permitting any community transmission compared with 37.5% who would, while the remainder had no clear view.

A majority of respondents were confident in state public health systems to suppress further outbreaks, and also in their own capacity to cope should further waves occur. By contrast, confidence in the Australian health care system’s capacity to limit HCW infections in subsequent waves was split, with 33 respondents (16.5%) not confident, 68 (34%) minimally confident, 88 (44%) moderately confident and 11 (5.5%) very confident.

Analysis of subgroups revealed two statistically significant findings.

First, Victorian clinicians reported being less confident in their state’s ability to suppress further outbreaks of COVID-19 compared with clinicians from other states. Second, advanced trainees reported being less confident in the Australian health care system’s capacity to limit HCW infections compared with their more experienced colleagues.

These findings correlate with the recent Victorian experience, with uncontrolled community transmission leading to restrictive interventions to reduce transmission. Given current work practices, advanced trainees are likely to have more direct face-to-face contact with patients with COVID-19 than their senior colleagues, and their concerns therefore warrant specific consideration within the broader effort to contain HCW infections.

Limitations: Only about one third of those eligible to participate completed the survey.

In summary, although a majority of infectious diseases (and associated specialty) clinicians favoured elimination, opinions were mixed. This reflects the great challenge and complexity in responding to COVID-19, with varying degrees of confidence in our capacity to succeed.

Dr Aaron Bloch is an infectious diseases and general medicine doctor at St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, where he has helped to plan and enact the hospital’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr Muhi is an infectious diseases physician and clinician-researcher with an interest in ID medical education. He is completing a PhD at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity.

Associate Professor Patrick Charles is a physician in infectious diseases and general medicine at Austin Health and has interests in medical education and improving antibiotic prescribing.

Professor M Lindsay Grayson is Head of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology at Austin Health and Professor of Medicine at the University of Melbourne.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

After 100 years the virus responsible for the 1918 pandemic is still amongst us. Without a vaccine, proposing elimination is a pipe dream. No vaccine means all those who are going to die from Covid-19 will eventually die from it. The best that can be hoped for is that they don’t all sicken over a short time frame and overwhelm the Health infrastructure.

Unfortunately there is no way you can afford to put COVID-19 strategies by itself into the equation of healthcare outcomes. Overzealous ID physicians who want elimination are showing their total ignorance or no care whatsoever for integrated medical care in our Australian society.

In Victoria we see a large number of oncology patients presenting late with up to 6 months delay with cancer which is going to translate into significant worsening of cancer mortality in the medium to long term.

There is also a significant increase of mental health issues which is going to get worse with time as Victorian businesses go under.

Clearly, those that support suppression do not dance, attend theatre or live music events.