SURVIVORS of childhood cancer are five times more likely to be diagnosed with a second primary cancer than the general population, researchers say.

In an analysis of national data from the Australian Childhood Cancer Registry, published in the MJA, more than 18 000 people who had been diagnosed with cancer during childhood were followed for up to 33 years. Researchers found an estimated 30-year cumulative risk of 4.4% (95% CI, 3.8–5.0%), and the risk of a new primary cancer was significantly higher than the general population with a standard incidence ratio (SIR) of 5.13 (95% CI, 4.65–5.67).

People who had had rhabdomyosarcoma as children had the highest relative risk of a second primary cancer. The researchers also reported that relative risk was particularly high for children who had undergone both chemotherapy and radiotherapy (SIR, 9.80; 95% CI, 8.35–11.5). Children who had been treated with chemotherapy only (SIR, 5.48; 95% CI, 4.69–6.40) and radiotherapy only (SIR, 4.46; 95% CI, 2.94–6.77) remained at higher risk, as were childhood cancer survivors who had had neither of these treatments (SIR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.64–2.78).

Relative risk was highest in the 5 years after the first diagnosis, the researchers reported, but was still significant at 20–33 years (SIR, 2.58; 95% CI, 2.02–3.30).

The researchers said that while the increased cancer risk gradually diminished over time, it never returned to that of the general population.

“Advances in treatment for childhood cancer in recent decades have significantly improved survival for many people with childhood malignancies,” the researchers wrote. “The challenge is to reduce treatment-associated morbidity without reducing survival.”

Dr Peter Downie, Director of the Children’s Cancer Centre at Monash Children’s Hospital, said it was important to consider therapeutic “eras” when looking at the rate of second primary cancers in childhood cancer survivors.

“The rate of second primary cancers in childhood cancer survivors is in fact decreasing, especially after the 1990s, as a result of the decreased use of radiation, especially in patients with leukaemia,” he said.

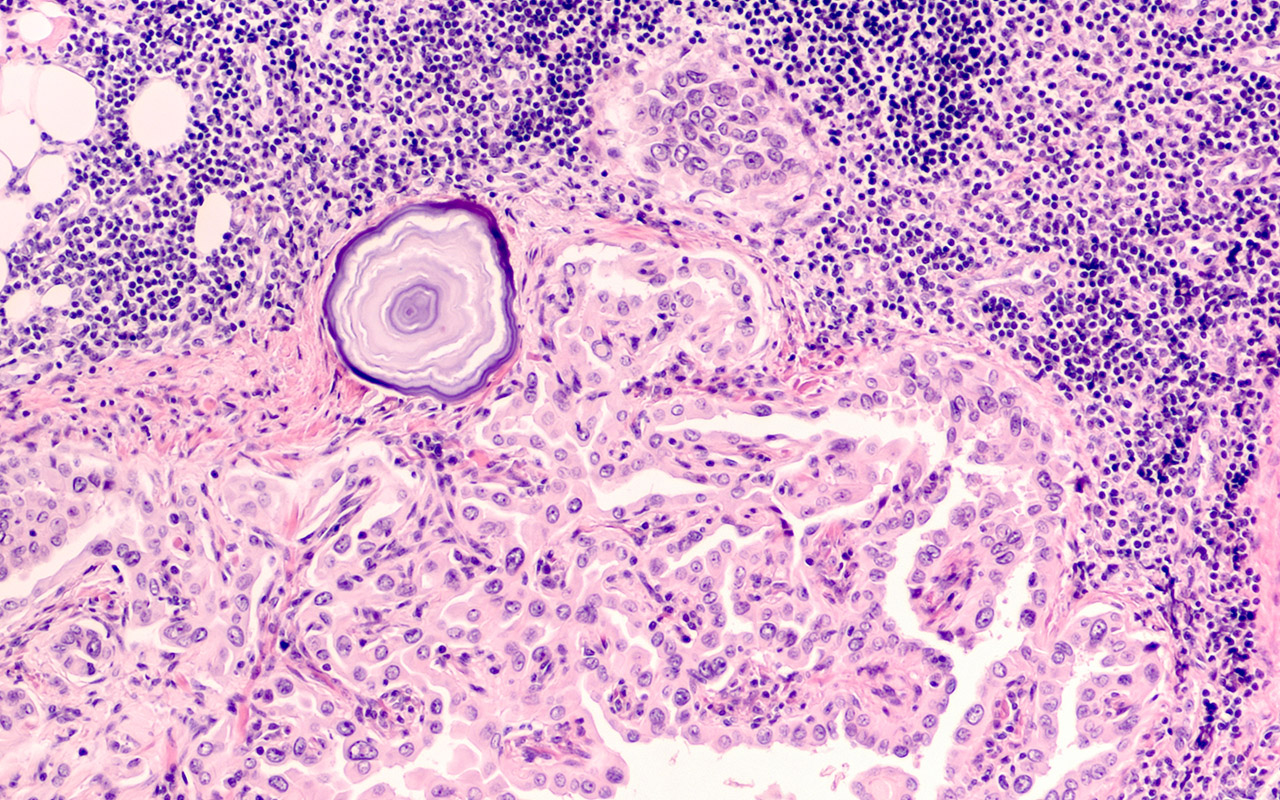

“Radiation-related solid cancers account for the highest group in all studies, including the current Australian study, and these include thyroid cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, brain cancers and skin cancers. Alkylating agents, such as cyclophosphamide, and topoisomerase inhibitors (both types 1 and 2) are also implicated. These chemotherapy-related second cancers are usually myelodysplasias and leukaemias, and occur at a shorter follow-up time, within 3 years of completion of treatment. The second solid primary cancers associated with radiation usually occur within the radiation field, and have a longer latency period, greater than 10 years.”

Dr Downie said there was also a smaller group of patients who would develop second cancers unrelated to their treatment, which was shown in the Australian study.

“There are known cancer predisposition syndromes such as Down syndrome and the increased risk of leukaemia, Li–Fraumeni syndrome, Lynch syndrome, Fanconi anaemia and others. These are all rare, but there are other more subtle predisposition diseases which are now coming to light, and these may account for up to 10% of childhood cancers,” he said.

“Environmental influences have been extensively studied in paediatric cancer, and the low mutation burden, coupled with almost no evidence of environmental factors implicated in causing childhood cancer, leaves us to conclude that there is clearly a familial or cancer predisposition factor in some patients. The more that we screen patients and their families, the more we are starting to find germline mutations that put these individuals at greater risk than the general population.”

Dr Downie said more than half of the second primary cancers could be detected by routine screening surveillance.

“It is important, therefore, to know what the ‘risk stratification’ is for each patient, which will depend on their primary cancer, the treatment they received (radiation site volume and dose, alkylating agents, topoisomerase inhibitors, and cumulative doses), whether there is an underlying cancer predisposition syndrome, and a family history,” he said.

“Every childhood cancer survivor should have a surveillance plan developed at the time of exit from their paediatric service, which should be a guide for GP management and follow-up.”

Dr Downie said the future of paediatric cancer medicine was shifting, and more trials were now looking at immunotherapy and other biological response modifiers, with the aim of eventually eliminating treatment such as radiation and alkylating agents.

“We have a much better understanding about the biology of many different cancers, and drug development is leaping forward to encompass more precise targeted therapies. BRAF inhibition of melanomas, bispecific antibodies for leukaemia, small molecules, immune ‘switch’ such as PD-L1 [programmed death-ligand 1] drugs, immune modulators, and monoclonal antibodies are all playing a part,” he said.

“Most of these first generation drugs have some effect … but also need the more traditional ‘power’ … of chemotherapy to enhance their effect,” he said. “But we are on the cusp of a whole range of newer generation therapies that will hopefully mean the elimination of more toxic treatment in the future.”

more_vert

more_vert