In fact, smallness makes people outward looking.

– Ten Remarkable Australians, Ian MacFarlane, Connor Court 2019

BEING ensconced in Coonabarabran, a small New South Wales town of about 3000 people, with an inability to travel and socialise, has presented me with time aplenty to think about all things coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and look at what is happening locally, around Australia and around the world.

The titbits below are the perspectives of a rural GP from a rural shire who visits a small rural hospital and owns a small rural general practice.

This is an article in two parts over 2 weeks. This week, I muse over the broader issues, and next week, I shall drill into more specific areas relating to practising clinicians.

The disease itself: we still know little

COVID-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS–CoV–2). We are dealing with a novel virus and the disease it causes. We have only known about this virus and the disease for 3–4 months.

Accordingly, we should avoid fixed ideas about how to diagnose, how to test, how it manifests, how to treat and how to declare it cured.

Of course, we have knowledge of other diseases and viruses to inform us and guide us; however, considerably more time needs to pass before we shall have reliable evidence and knowledge about COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2.

Experts abound everywhere. Some specialise in epidemiological models, others specialise in intensive care, while others are infectious disease and respiratory specialists.

However, we have to beware of those “experts” who are peddling agendas, such as health care reformists, anti-vaxxers and, of course, those with financial interests.

Doctors on the ground should not be excluded from the conversation. The internet is full of articles and reports that describe a spectrum of disease that ranges from a minor catarrh to multi-organ failure. In my view, it is dangerous to think of COVID-19 as simply a respiratory tract illness.

Because every nation is testing, treating and reporting in different ways, we simply cannot draw conclusions yet. And, of course, every country has different demographics, different economics and different health systems.

We need to keep open minds and follow the evolving conversation and exchange of information as best we can.

Australia’s national response versus overseas: we appear to be winning

We are practising social distancing and testing many patients according to clinical criteria based on risk profile.

Australia has taken the path of keeping persons apart, minimising economic and social activity. This is to “flatten the curve”, a term that has become part of the vernacular. Flattening the curve aims to minimise spread and allow our health services to cope with the number of sick patients.

Because COVID-19 appears to have arrived in Australia a few weeks after Asia and Europe, we have benefited from observing what has worked and not worked on those continents.

In Australia, some people feel we should be stricter in what we are doing, and some people feel we have the balance correct.

Others feel that the economic and social costs do not justify our response and that panic has resulted in an over-reaction to the pandemic.

Overseas, the same debates continue between those who want to keep people apart and those who want herd immunity to develop faster.

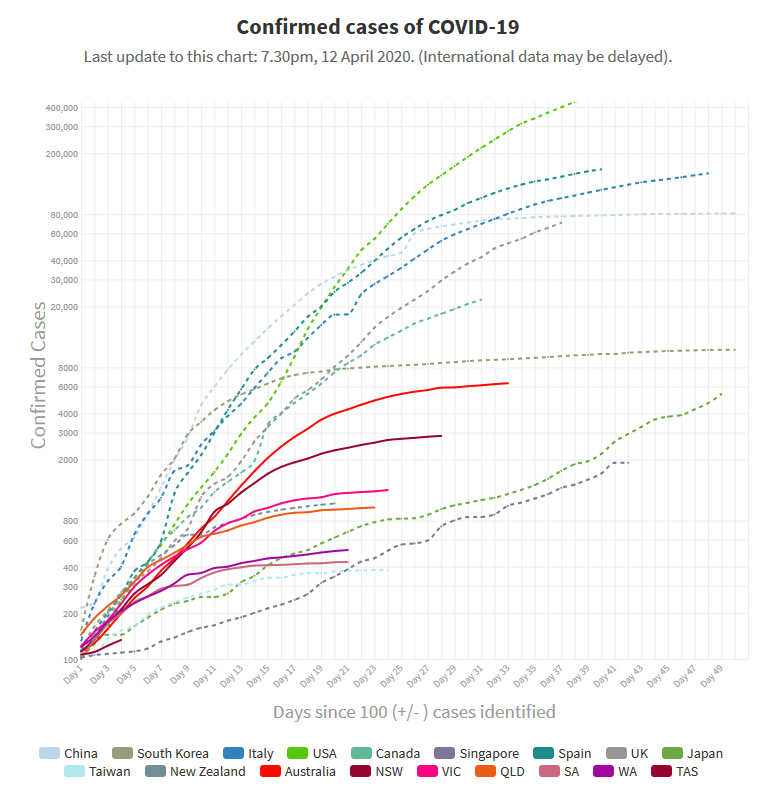

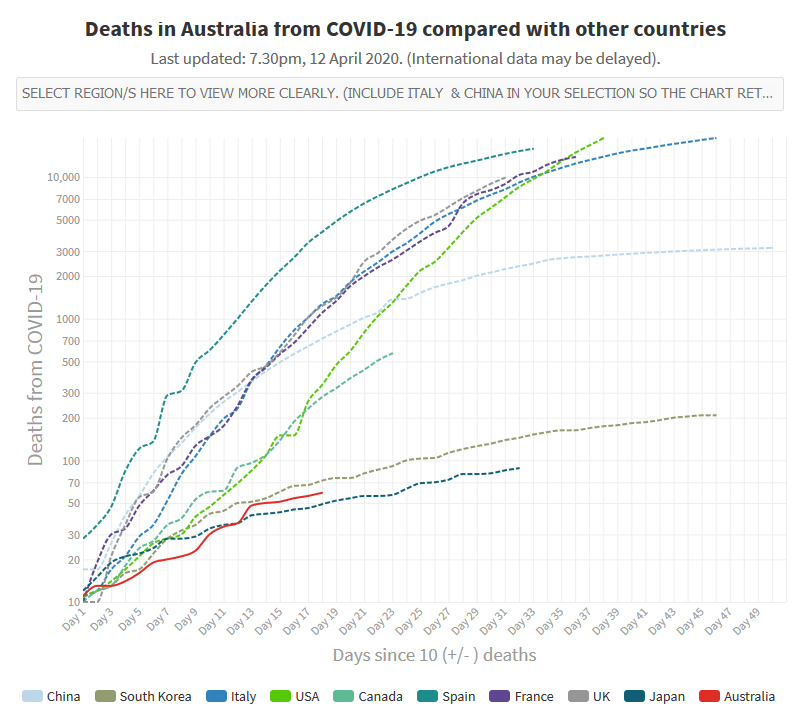

We have reason to be pleased with the Australian situation at the time of writing: the number of new cases appears to be decelerating and the number of deaths per capita is among the lowest in the world.

Source: Our World In Data • China had 81,086 cases at day 60

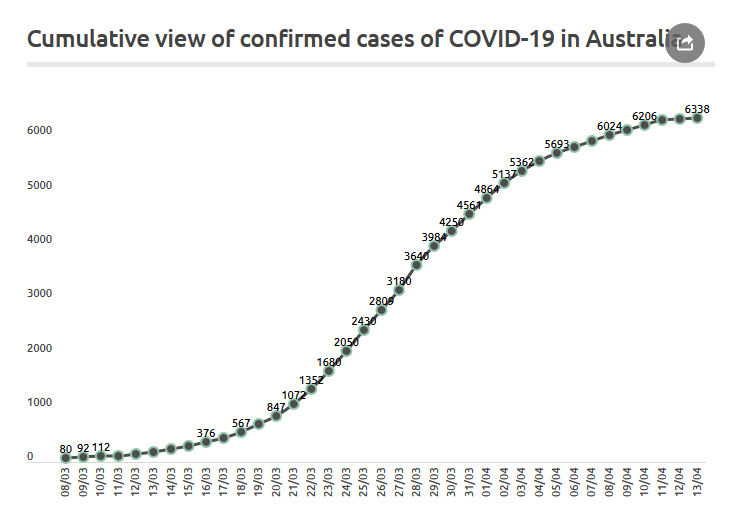

This chart shows the last month. Source: Coronavirus in Australia

Source: Our World In Data

The politicians: what they’ve got right

Ultimately, the decisions are made by the politicians. At times like these, nobody can envy their predicament.

They have formed a National Cabinet crossing party lines. They’re spending a lot of money to prop up the economy. They’ve opened up Medicare to telehealth and COVID-19 testing. They’ve restricted travel.

The politicians: what they need to do now

Messaging needs to be clearer

We are being bombarded by information from every level of government and every government department and organisation. Every time an organisation puts its spin on things, inconsistencies arise.

For example, the rules about children and schools. On the one hand, we wanted children to keep away and banned them from hospitals and aged care facilities. On the other hand, we allowed them to attend school, while also allowing parents to keep them home. School teachers I have seen over the past few weeks have often been confused about what is expected of them.

Testing protocols need to be freed up

The fine details change as the pandemic unfolds, as they should. We need to be agile.

Clinicians have been frustrated about restrictions on testing. Tests are often being requested in good faith, only to be rejected by pathology laboratories or hospitals.

Clinicians may feel belittled and unappreciated when this happens, and patients may experience frustration and angst at not knowing whether they are infected.

Personal protective equipment

Demand is far outstripping supply. Clinicians feel vulnerable. We feel that the personal protective equipment (PPE) we have is inadequate. If supply runs out, many clinicians may down tools.

Employers worry about employees becoming infected.

Supply chains and logistics of PPE need to be improved.

Next week, I shall look at some specific areas, relating to the way our regulators and administrators are handling the pandemic.

I wish to congratulate all front-line health care workers in Australia for their performance during the pandemic. The courage and self-sacrifice being shown is admirable and inspiring.

Happy Easter to all of you!

Dr Aniello Iannuzzi is a Visiting Medical Officer at Coonabarabran District Hospital, a GP, and a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Sydney and University of New England. He is Chair of the Australian Doctors’ Federation.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

I think your point about prejudging the nature of the disease is very well made. Two very disturbing cases in point from the developing world have emerged in the last few weeks–from Jakarta, pointing to a 40% increase in all-cause deaths in the month of March, and this morning from Ecuador again talking about a massive increase in deaths (all cause) in a country that is logging only 400 odd official COVID-19 cases. I think the extent of the disease will only really be able to measured in the rear view, and it may be a very distressing sight.

The difficulty in obtaining adequate PPE protocols and supplies needs to be addressed through a better governance structure. There needs to be a national body to coordinate the large number of GP practices around the country. If there is already an existing body, it needs to be strengthened so that policies and protocols can be easily distributed.

I think we need zero new cases for a period of 2-4 weeks so we have eradicated this virus from our community and then we can lift restrictions except international travel. We can then keep our borders closed to international travel except from countries with no covid 19.