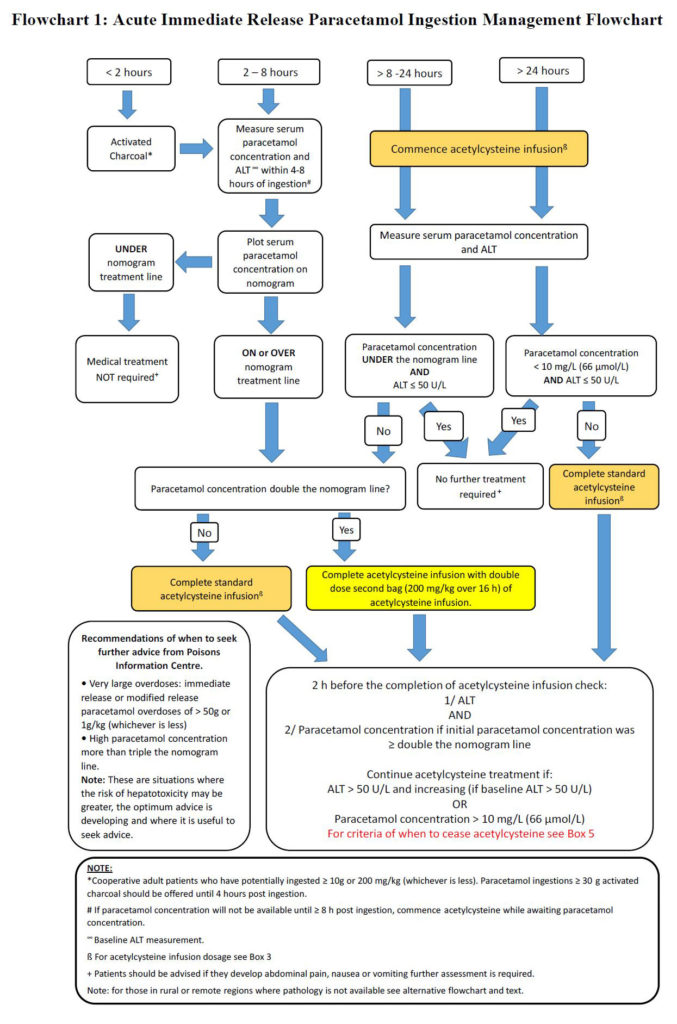

A SIMPLIFIED, safer acetylcysteine infusion regimen and new flow charts for modified release paracetamol ingestions and rural and remote treatment pathways are some of the changes to practice recommended by an update to the paracetamol poisoning management guidelines.

Recent evidence has prompted the changes, according to the authors of the updated guideline summary published by the MJA.

Previous guidelines were published by the MJA in 2015, but further research has emerged, particularly regarding acetylcysteine regimens, massive paracetamol ingestions, and modified release paracetamol ingestion.

The authors, led by Dr Angela Chiew, an emergency physician and toxicologist at the Prince of Wales Hospital and a clinical toxicologist at the NSW Poisons Information Centre, made three adjusted recommendations to reflect that evidence.

- The new guidelines recommend a two-bag acetylcysteine infusion regimen (200 mg/kg over 4 hours, then 100 mg/kg over 16 hours); this has similar efficacy but significantly reduced adverse reactions compared with the previous three-bag regimen.

In an exclusive podcast, Dr Chiew told InSight+ that recent research had highlighted the need to reassess the traditional three-bag regimen (here and here).

“With the three-bag regimen, you’ve got a bolus dose over anywhere between 15 minutes and an hour, and that bolus was associated with adverse effects, such as people getting an anaphylactoid reaction,” Dr Chiew said.

“That [adverse reaction] rate was quite high, so what various groups have studied is combining the first two bags and creating a two-bag protocol. The loading dose is given a lot slower, over 4 hours. Instead of giving 150 mg/kg over a short time and then 50 mg/kg for 4 hours, they combined them together and give 200 mg/kg over 4 hours.

“They found that [the two-bag regimen] significantly decreased the rate of the non-IgE anaphylaxis, or anaphylactoid reaction. It probably reduces error as well, because although it hasn’t been proven, it’s simpler because it’s only two bags.

“Nearly all the toxicology units in Australia, bar a few, are using the two-bag regimen, and a lot of the hospitals have changed anyway, so we thought it’d be best if the whole country changed.”

- Massive paracetamol overdoses that result in high paracetamol concentrations more than double the paracetamol nomogram line should be managed with an increased dose of acetylcysteine.

Dr Chiew and colleagues wrote that “Patients with a high initial paracetamol concentration (greater than double the nomogram line) are at increased risk of acute liver injury if given standard acetylcysteine regimens”. Fresh evidence from Australia and the US showed that patients “with an initial paracetamol concentration greater than double the nomogram line may benefit from an increased dose of acetylcysteine”.

Dr Chiew told InSight+ that:

“Having increased acetylcysteine decreases their risk of liver injury, and so we have formally put that recommendation in the guidelines.”

- All potentially toxic modified release paracetamol ingestions (≥ 10 g or ≥ 200 mg/kg, whichever is less) should receive a full course of acetylcysteine. Patients ingesting ≥ 30 g or ≥ 500 mg/kg should receive increased doses of acetylcysteine.

“Modified release paracetamol is actually a combination of immediate release and slow release. That’s the majority of the tablets – slow release. You can imagine what happens in an overdose after you take it.

“The treatment was extrapolated from immediate release [protocols]; it used the nomogram to do two levels [of treatment], 4 hours apart. But that was never subject to a study and was extrapolated from what we thought from immediate release data and more from simulated overdoses,” she said.

“What we and the group in Europe did was started collecting cases of these overdoses.

“Unfortunately, in Australia, these overdoses are often quite large because the only pack size available is 96 tablets – [modified release paracetamol] doesn’t come in any smaller pack size. So, they tend to be larger overdoses.

“What we found was that the paracetamol levels and the absorption were quite erratic. People initially could have quite low levels and then they could go quite high. It’s really quite unpredictable, and we found that with standard treatment, people were still at risk of getting liver injury.

“So, we recommend now that everyone who takes a toxic dose [of modified release paracetamol] will get a full course of treatment. We also recommend that the second bag of the two-bag regimen be doubled to 200 mg/kg intravenous acetylcysteine over 16 hours, instead of 100 mg/kg over 16 hours.”

In addition, Chiew and colleagues included a management flow chart for rural and remote centres with limited pathology facilities.

“Many rural and remote health care facilities do not have access to 24-hour pathology or have very limited pathology services (eg, point of care testing only),” they wrote.

“These facilities can still manage certain acute paracetamol poisoning cases, provided acetylcysteine is available and the patient is not at high risk of developing acute liver injury.

“[We have outlined] the management of acute immediate release paracetamol ingestion for rural and remote facilities and the criteria for determining when transfer is required.”

more_vert

more_vert