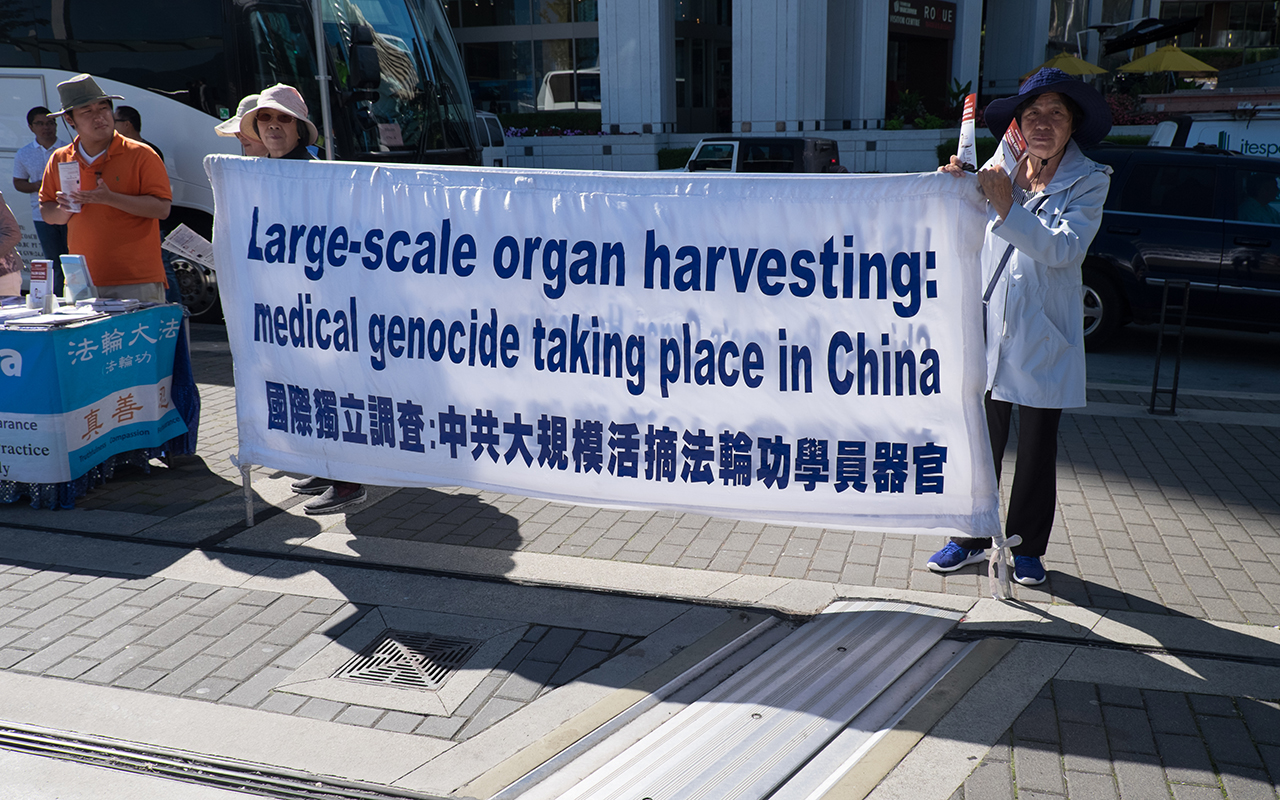

China harvesting organs from religious minorities, UN told

The lawyers for the independent China Tribunal have told the United Nations’ Human Rights Council that China is harvesting and selling organs from “persecuted religious and ethnic minorities”. Presenting the final report of the Tribunal last week, Mr Hamid Sabi told the Council the UN had a “legal obligation” to act given the Tribunal had found “the commission of crimes against humanity against the Falun Gong and [Uyghur minorities had] been proved beyond reasonable doubt”. According to a report in The Independent, the organ transplant industry is estimated to earn China more than $1 billion a year. Sir Geoffrey Nice, QC, chair of the China Tribunal, told a separate NGO-hosted UN event that the international community “can no longer avoid what it is inconvenient for them to admit”. Mr Sabi concluded his speech to the Human Rights Council with: “Victim for victim and death for death, the gassing of the Jews by the Nazis, the massacre by the Khmer Rouge or the butchery to death of the Rwanda Tutsis may not be worse than cutting out the hearts and other organs from living, blameless, harmless, peaceable people.”

Tassie devils may tell us how human cancers avoid the immune system

Researchers from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, in collaboration with Cancer Research UK, have uncovered a new way that some human cancers can hide from the body’s immune system, a feature they share with tumours from an unlikely source: the Tasmanian devil. Published in Cancer Cell, the study found that some human, mouse and Tasmanian devil cancers can reduce the amount of immune-stimulating MHC class I (MHC-I) proteins present on their surface, effectively masking them from being recognised and destroyed by killer immune cells. Whether or not MHC-I appears on the cell surface can depend on the activity of other proteins inside the cell. By systematically knocking out all the genes in the human genome using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, the researchers looked for clues as to which proteins were important in controlling MHC-I at the surface. They found that a group of proteins that collectively form an epigenetic protein complex, known as PRC2, acts inside the cell to switch off the genes required for MHC-I production. When they looked in human cancers such as lung cancer, neuroblastoma and Merkel cell cancer, they found that tumours with high levels of PRC2 proteins had reduced MHC-I and this was associated with an impaired ability of tumour-killing immune cells to recognise these cancers. They also found the exact same process also occurs in mouse models of lung cancer and in Tasmanian devil facial tumours, a deadly cancer of the mouth and face that has decimated the wild Tasmanian devil population. When the researchers used targeted drugs to effectively shut down the PRC2 pathway in a mouse model of small cell lung cancer, they found they could re-establish MHC-I expression which led to more effective immune-mediated tumour cell killing.

Anxiety disorders linked to disturbances in mitochondria

Mitochondria provide energy for cellular functions, but those activities can become disturbed when chronic stress leads to anxiety symptoms in mice and humans, according to Finnish research published in PLoS Genetics. Chronic stress due to stressful life events, such as divorce, unemployment, loss of a loved one and war, is a major risk factor for developing panic attacks and anxiety disorders. Not all people who experience stressful life events go on to develop a disorder, however, and scientists are trying to identify the pathways that lead some people to be resilient to stress, while others become vulnerable to anxiety. In the current study, researchers studied mice that developed symptoms of anxiety and depression, such as avoiding social interactions, after being exposed to high levels of stress. Using a multipronged approach, they tracked changes in gene activity and protein production in a key region of the brain for stress response and anxiety. The analysis pointed to a number of changes in the mitochondria in the brain cells of mice exposed to frequent stress, compared with the non-stressed mice. Furthermore, testing of blood samples collected from patients with panic disorder after a panic attack also showed differences in mitochondrial pathways, suggesting that changes to cellular energy metabolism may be a common way that animals respond to stress. The discovery that high levels of stress may substantially affect the functioning of the mitochondria opens up new avenues of research into stress-related diseases such as panic disorder and other anxiety disorders.

What’s new online at the MJA

Podcast: Professor Susan Sawyer, Chair of Adolescent Health at the University of Melbourne, Director of the Centre for Adolescent Health at the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, and President of the International Association for Adolescent Health, talks about the redefinition of adolescence and the implications for paediatricians … OPEN ACCESS permanently.

Research letter: Health care for older people in rural and remote Australia: challenges for service provision

Gardiner et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.50277

The most frequent reason for retrieval, myocardial infarction, requires early treatment and extensive long term management … OPEN ACCESS permanently.

Research letter: Illegal and risky riding of electric scooters in Brisbane

Haworth and Schramm; doi: 10.5694/mja2.50275

The availability of helmets and the enforcement of helmet rules by police must be ensured … OPEN ACCESS permanently.

Research letter: Clinically important sport-related traumatic brain injuries in children

Eapen et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.50311

The proportion of head injuries that is acutely clinically significant is greater for recreational sports than for contact sports associated with risk of concussion … OPEN ACCESS permanently.

more_vert

more_vert