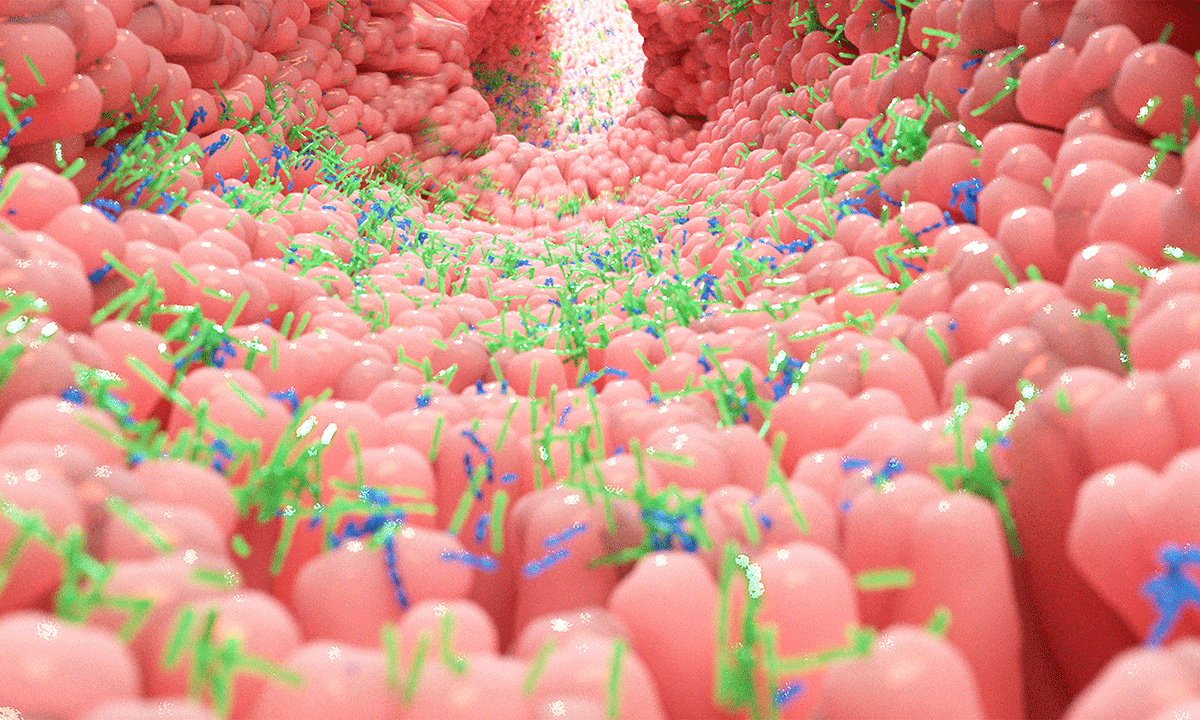

Gut microbes respond differently to foods with similar nutrition labels

Foods that look the same on nutrition labels can have vastly different effects on our microbiomes, according to US research published in Cell Host and Microbe. The investigators enrolled 34 participants to record everything they ate for 17 days. Stool samples were collected daily, and shotgun metagenomic sequencing was performed. This allowed the researchers to see at very high resolution how different people’s microbiomes, as well as the enzymes and metabolic functions that they influence, were changing from day to day in response to what they ate. It provided a resource for analysing the relationships between dietary changes and how the microbiome changes over time. What the researchers observed was a much closer correspondence between changes in the diet and the microbiome when they considered how foods were related to each other rather than only their nutritional content. For example, two different types of leafy greens like spinach and kale may have a similar influence on the microbiome, whereas another type of vegetable like carrots or tomatoes may have a very different impact, even if the conventional nutrient profiles are similar. The researchers developed a tree structure to relate foods to each other and share statistical information across closely related foods. Two people in the study consumed nothing but Soylent, a meal replacement drink that is popular with people who work in technology. Although it was a very small sample, data from these participants showed variation in the microbiome from day to day, suggesting that a monotonous diet doesn’t necessarily lead to a stable microbiome.

Evolutionary discovery to rewrite textbooks

Scientists at the University of Queensland have upended biologists’ century-old understanding of the evolutionary history of animals, using new technology to investigate how multicelled animals developed. The team mapped individual cells, sequencing all of the genes expressed, allowing the researchers to compare similar types of cells over time. “We’ve found that the first multicellular animals probably weren’t like the modern-day sponge cells, but were more like a collection of convertible cells,” the authors said. “The great-great-great-grandmother of all cells in the animal kingdom, so to speak, was probably quite similar to a stem cell. This is somewhat intuitive as, compared with plants and fungi, animals have many more cell types, used in very different ways – from neurons to muscles – and cell flexibility has been critical to animal evolution from the start.” The findings disprove a long-standing idea that multicelled animals evolved from a single-celled ancestor resembling a modern sponge cell known as a choanocyte. Mapping individual cells allowed the researchers to compare similar types of cells over time. This meant they could tease out the evolutionary history of individual cell types, by searching for the “signatures” of each type. “Biologists for decades believed the existing theory was a no-brainer, as sponge choanocytes look so much like single-celled choanoflagellates – the organism considered to be the closest living relatives of the animals,” the authors said. “But their transcriptome signatures simply don’t match, meaning that these aren’t the core building blocks of animal life that we originally thought they were. Now we have an opportunity to re-imagine the steps that gave rise to the first animals, the underlying rules that turned single cells into multicellular animal life.” The study was published in Nature.

Things that go bump in the night: new “normal” for baby movements

A University of Auckland-led study shows it is entirely normal in late pregnancy for babies to be more active in the evening and bedtime, and that babies’ movements tend to keep getting stronger even as they come to term. It also showed that – contrary to advice given to some women – neither a cold drink nor sweet food will prod babies into action. The study of pregnant women’s own observations, published in PLOS One, debunks some myths about babies’ movements during pregnancy and gives much-needed, clear guidance to women and their health professionals about what is normal. The research team interviewed pregnant women in their third trimester (after 28 weeks of pregnancy) about the nature and frequency of their babies’ movements, and analysed the responses of those who gave birth to a live, well grown baby after 37 weeks. The 274 included women were from seven regions of Aotearoa New Zealand and included diverse ethnic representation. The main findings were: 59% of women reported feeling movements getting stronger in the previous 2 weeks; strong movements were felt by most women in the evening (73%) and at night-time, including bedtime (79%); women were more likely to perceive moderate or strong movements when sitting quietly compared with other activities, such as having a cold drink or eating; almost all women reported feeling their babies hiccup. There is a growing appreciation of how circadian patterns may be important in health, and researchers are investigating how timing of assessments and therapies can improve outcomes across many areas of health care. The take-home message for pregnant women: if your baby usually gets busy at night, rest (if you can) assured. If you’re concerned that your baby is moving less often, less strongly or not moving in the evening as they normally would, don’t wait until the next day for a check-up.

What’s new online at the MJA

Narrative review: Updates and advances in the treatment of Parkinson disease

Hayes et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.50224

New therapies show promise, but effective treatment of non-motor, non-dopaminergic symptoms remains a major challenge … PREMIUM CONTENT

Research: HPV vaccination coverage and course completion rates for Indigenous Australian adolescents, 2015

Brotherton et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.50221

Improving completion rates for Indigenous Australian women are needed to end their higher burden of cervical cancer … OPEN ACCESS permanently

Podcast: Associate Professor Julia Brotherton, Medical Director of VCS Foundation’s Population Health Services, talking about HPV coverage in Indigenous adolescents … OPEN ACCESS permanently

Podcast: Dr Paul Kruger, haematologist at Fiona Stanley Hospital in Perth, talking about deep vein thrombosis, diagnosis and management … OPEN ACCESS permanently

more_vert

more_vert