Pill testing could save the lives of first-time ecstasy users

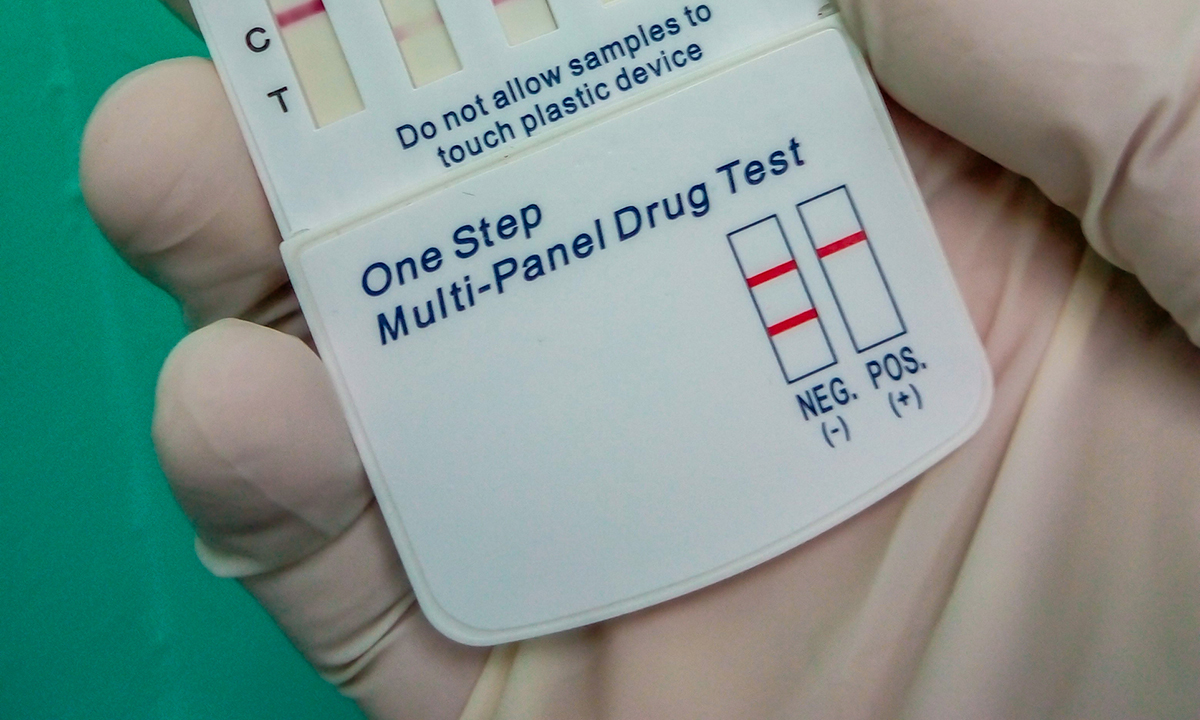

Pill-testing services at music festivals may be most effective in reducing harm for people trying ecstasy for the first time, but less effective for prior users, according to research from Edith Cowan University, published in Drug and Alcohol Review. The study looked at ecstasy-using intentions following different pill test scenarios to determine the factors that predict subsequent risky behaviour. Over 250 music festival attendees were presented with three hypothetical pill test scenarios and reported their risk intentions, ecstasy use history and sensation seeking. The findings suggested that people who attend a festival and might be looking to try ecstasy for the first time are most cautious after a pill test, regardless of the outcome of the test. Prior ecstasy users (60% of the sample), were only more likely to reduce their harm intentions if the ecstasy contained a toxic contaminant, not if the test revealed a high dose or an inconclusive result. If the participant was a prior ecstasy user who was also high in sensation seeking, then they were at the greatest risk of harm, even after participating in the pill test. Experienced ecstasy users were no more knowledgeable than novices when it came to safe dosage amounts and harmful ingredients. Festival attendees would be willing to pay an average $12 subsidy to fund pill testing services, the researchers found. Dr Ross Hollett, study author, said introducing counselling and drug education services alongside formal pill testing could further reduce the risk of harm.

Childhood respiratory disorders may be diagnosed with a smartphone

Automated cough analysis technology incorporated in a smartphone app could help diagnose childhood respiratory disorders, according to an Australian study published in Respiratory Research. Researchers at Curtin University and the University of Queensland showed that a smartphone app had high accuracy (between 81% and 97%) in diagnosing asthma, croup, pneumonia, lower respiratory tract disease and bronchiolitis. To develop the app, the authors used similar technology to that used in speech recognition, which they trained to recognise features of coughs which are characteristic of five different respiratory diseases using a machine learning approach. The researchers then used the app to categorise the coughs of 585 children between ages 29 days to 12 years who were being cared for at two hospitals in Western Australia. The accuracy of the automated cough analyser was determined by comparing its diagnosis with a diagnosis reached by a panel of paediatricians after they had reviewed the results of imaging, laboratory findings, and hospital charts and conducted all available clinical investigations. The positive percent (clinical diagnosis-positive patients who are also positive for the index test) and negative percent agreement (clinical diagnosis-negative patients who are also negative for the index test) values between the automated analyser and the clinical reference were as follows: asthma (97%, 91%), pneumonia (87%, 85%), lower respiratory tract disease (83%, 82%), croup (85%, 82%), bronchiolitis (84%, 81%).The authors noted that the technology developed for this study is able to provide a diagnosis without the need for clinical examination by a doctor in person, addressing a major limiting feature of existing telehealth consultations, which are used to provide clinical services remotely. Removing the need for a clinical examination may allow targeted treatments to begin sooner. Dr Porter said: “As the tool does not rely on clinical investigations, it can be used by health care providers of all levels of training and expertise. However, we would advise that where possible the tool should be used in conjunction with a clinician to maximise the clinical accuracy.”

Did sex evolve to beat transmissible cancers?

An international team of researchers, including from Deakin University and the University of Tasmania, has found that sexual reproduction is favoured by selection because, unlike asexual reproduction, it not only provides important evolutionary advantages in constantly changing environments but also prevents the invasion of transmissible cancer or “cheater” cells. One of the greatest enigmas of evolutionary biology is that while sex is the dominant mode of reproduction among multicellular organisms, asexual reproduction appears much more efficient and less costly. Because asexual reproduction leads to identical (“clonal”) organisms, this mode of reproduction is risky due to the possibility of being invaded by clonal infectious cell lineages (ie, transmissible cancers). Conversely, sexual reproduction decreases the compatibility of contagious cancer cells with their hosts, limiting individual infection risk, as well as the risks of transmission between parent and offspring. In a study published in PLOS Biology, the researchers claim that, to their knowledge, “the proposed role of transmissible cheater cells as initiator and driver force underlying the evolution of sexual reproduction is a novel explanation that will contribute to a paradigm shift in our understanding of evolution”. Multicellular organisms are societies of cooperating clonal cells that emerged and evolved one billion years ago. A key point in the evolution of multicellular organisms was therefore the ability to prevent cheater cells from overexploiting the cooperative system; this evolutionary constraint favoured the emergence of the many known mechanisms that suppress cancer, notably the immune system. Whatever the efficiency of these mechanisms, a prerequisite of all these defences is the ability to recognise cheater cells from normal ones. Not only did first multicellular organisms have to deal with their own cheater cells, they also had to evolve adaptations to prevent them being colonised by foreign malignant cells (ie, infectious ones). Sexual reproduction also generates genetic variation that facilitates the detection of foreign cells, the first and critical step of immune protection. Although relatively rare, transmissible cancers do exist (eg, Tasmanian devils, dogs, bivalves), and increasing evidence suggests that most, if not all, malignant cells are potentially transmissible provided a suitable transmission route is offered. Given the ubiquity of cancer in multicellular organisms, in combination with the plethora of potential transmission routes, sexual reproduction may have been favoured as a less risky, more profitable option to produce viable offspring despite its associated costs.

What’s new online at the MJA

Research: Routine cervical screening by primary HPV testing: early findings in the renewed National Cervical Screening Program

Machalek et al; doi: 10.5694/mja18.01236

The renewed program is performing as expected during the initial HPV screening round … OPEN ACCESS permanently

Perspective: Ending preventable stillbirths among migrant and refugee populations

Yelland et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.50199

There is an urgent need for stronger evidence to inform tailored health care strategies to address perinatal health disparities … FREE ACCESS for 1 week

Podcast: Associate Professor Jane Yelland, Senior Research Fellow at the Intergenerational Health Research Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, talking about stillbirth rates in migrant and refugee women … OPEN ACCESS permanently

Research: Trauma‐related admissions to intensive care units in Australia: the influence of Indigenous status on outcomes

Magee et al; doi: 10.5694/mja2.12028

The significantly higher population rate of major trauma‐related ICU admissions for Indigenous people suggests a health gap similar to those for chronic disease and mental health disorders … OPEN ACCESS permanently

more_vert

more_vert