MORE than one in five Australian adults have cardiovascular disease (CVD). Prevalence rates of CVD are higher for people living in inner regional (25%) and outer regional and remote areas (22%), compared with people living in major cities (21%). These statistics are especially concerning when you consider age-standardised potentially avoidable death rates from acute cardiac events: 96 per 100 000 in major cities versus 256 per 100 000 in very remote areas. While 5-year survival rates from cardiovascular events are considered acceptable, they appear to be inversely correlated with increasing remoteness.

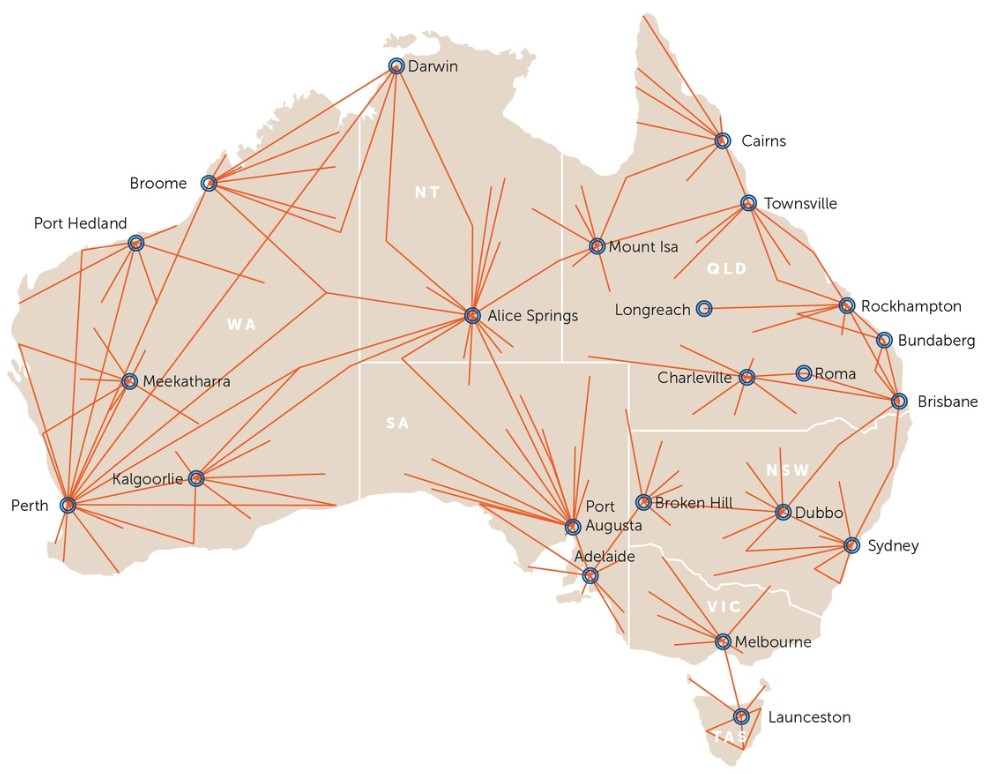

Are these observations related to emergency cardiac care in the bush? Yes, in part, but the issues are far reaching and far more complex. The Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) has a distinguished 91-year history of providing emergent care to those who reside in rural, regional and remote Australia (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Royal Flying Doctor Service aeromedical coverage. Source: About the Royal Flying Doctor Service

Nationally, the RFDS conducted nearly 34 000 aeromedical retrievals during 2017–2018, of which 7389 (22%) were for patients with “diseases of the circulatory system”. Of this subgroup, where more detailed in-flight working diagnosis was available, the main reasons for retrieval included acute myocardial infarction and/or cardiac arrest (38%), angina or ischaemic heart disease (15%), heart failure (3.6%) and/or arrhythmia (9%).

Retrievals were predominantly from remote areas throughout Australia, areas known to have a low provision of basic, essential health care services. With an estimated average primary evacuation cost of $7161.50 per patient (2017–2018), the resource implications to the RFDS, and its funders, are staggering.

ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a known major cause of cardiac mortality and carries the highest risk of cardiovascular death. In the 30% of patients with STEMI who fail to reperfuse with thrombolytic therapy, it is recommended that immediate transfer to a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)-capable hospital for interventional coronary angiography occurs (here). Not surprisingly, increased cardiovascular death rates from STEMI relate to time delays in accessing reperfusion therapy – notably, 14% greater mortality in STEMI for rural and remote patients compared with patients in major cities, with even substantially lower rates of definitive revascularisation for rural and regional patients (15% v 36%; P < 0.001) (here and here). Decreased rates of timely definitive treatment drive poorer outcomes and a greater risk of recurrent events. Of the rural and regional patients who present with acute myocardial infarction, 83% present first to a non-PCI capable hospital and require transfer to PCI-capable centres if they are to receive definitive reperfusion management, with expedient transfers being a significant challenge.

Studies in several states in Australia have had success in improving outcomes via acute telehealth and remote support and electrocardiogram reading services, such as those operative within NSW’s Statewide Cardiac Reperfusion Strategy. While these strategies are gradually making in-roads into improving the rates of timely transfers (here and here) of patients from rural areas to PCI-capable hospitals, renewed attention should return to the prevention of new coronary events.

Once a patient has an acute event and is discharged back to the bush, are they “out of sight and out of mind”? While this is never intended, the harsh reality is that most of these patients do not have easy access to chronic disease management services. Access to specialist care is problematic outside metropolitan areas in Australia, with fewer than half the number of specialists per capita in regional areas. Patients who live in remote areas travel long distances (in excess of 60 minutes) to attend hospitals, general practitioners and emergency departments.

Primary health care, as with the management of all chronic diseases, is essential in both the primary and secondary prevention of CVD (Gardiner and colleagues, in press). Effective evidence-based pharmacological interventions and non-pharmacological interventions, such as lifestyle management and modification of risk factors, remain the pillars of prevention of complications and prevention of future cardiac events. However, registered chronic disease management services such as “hospital in the home” and cardiac rehabilitation services are poorly accessible to patients who reside in outer regional and remote areas.

Recognising that many rural and remote populations do not have access to primary health care, the RFDS has established primary health care services throughout rural Australia. The types of services the RFDS provides vary, and do so in harmony with existing local health services in specific operating regions. However, the overarching aim for all the RFDS’ primary health care clinics is to improve the wellbeing of rural and remote Australians by means of disease prevention and maintenance of good health. Hence, beyond acute cardiac care, the RFDS is well placed to provide primary and secondary prevention.

A mobile cardiac rehabilitation service using a similar model to the successful RFDS dental service could be considered for rural and remote areas without access to cardiac rehabilitation services. This unit could visit remote communities, remove attendance access barriers and help ensure adherence to lifestyle modification measures and pharmacological therapy. Such a cardiac service would work with existing RFDS primary health care centres, local GPs and pharmacists, and would ideally involve a cardiac nurse specialist, a dietitian, an exercise physiologist and a social worker. Their expertise would be enhanced by regular input by a cardiologist and psychologist via telehealth support.

To make a real impact on the excess cardiovascular deaths in rural and remote Australia will need coordinated strategies aimed at improving survival from acute cardiac conditions, reducing the gap between metropolitan and rural rates of definitive revascularisation, ensuring follow-up and secondary prevention.

While it seems obvious that such cardiac services are necessary in the bush, this unmet need equally applies to better gastrointestinal, liver, respiratory, neurological, geriatric and cancer care. As a nation, we should all aspire to create and promulgate health promotion activities that will prevent disease and disease complications and, thus, reduce demand for specialised services or, for that matter, aeromedical retrievals for potentially preventable acute disease conditions. These are ambitious aspirations, well motivated and heartfelt, but they demand long term approaches and collaboration of existing agencies, as well as investment strategies from diverse sectors.

Be not still our beating hearts.

Dr Fergus Gardiner is Manager of Research and Policy with the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

Dr Ruth Arnold is a cardiologist at Orange Base Hospital in Orange, NSW.

Professor Narci Teoh is Professor of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the Australian National University, and is President of the Gastroenterological Society of Australia.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert