Extending time limit for clot-busting stroke drugs

Researchers from Royal Melbourne Hospital, the University of Melbourne and Monash Health, have found that the time to treat patients with ischaemic stroke can be doubled. One in five patients with stroke had stroke onset in their sleep and this will be life-changing for them. The EXTEND randomised clinical trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found the initial window of 4.5 hours from symptom onset could now be pushed to 9 hours, given solid evidence of “brain to save” on advanced brain imaging. The trial compared the effectiveness of alteplase – a thrombolytic drug used to treat ischaemic stroke – versus placebo for reducing disability after stroke. The international trial involved 225 participants from a large multicentre collaboration across 25 hospitals in Australia, New Zealand, Finland and Taiwan. The authors found that the administration of alteplase between 4.5 and 9 hours after stroke onset resulted in a higher percentage of patients with no or minor neurologic defects (40/113 patients, 35.4%) than the use of placebo (33/112 patients, 29.5%) (adjusted risk ratio, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.01–2.06; P = 0.04). There were more cases of symptomatic cerebral haemorrhage in the alteplase group than in the placebo group. Symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage occurred in 7 patients (6.2%) in the alteplase group and in 1 patient (0.9%) in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio, 7.22; 95% CI, 0.97–53.5; P = 0.05). “Our study used imaging of brain blood flow to select patients and showed that alteplase increased the number of patients who were able to return to all their usual activities by 44% compared to placebo,” the authors said. “These results shift the stroke paradigm from using a clock to determine eligibility for clot-dissolving treatment to using brain imaging to identify whether there is brain tissue that can be saved in the individual patient. This will reduce the burden of stroke-related disability in Australia and worldwide.”

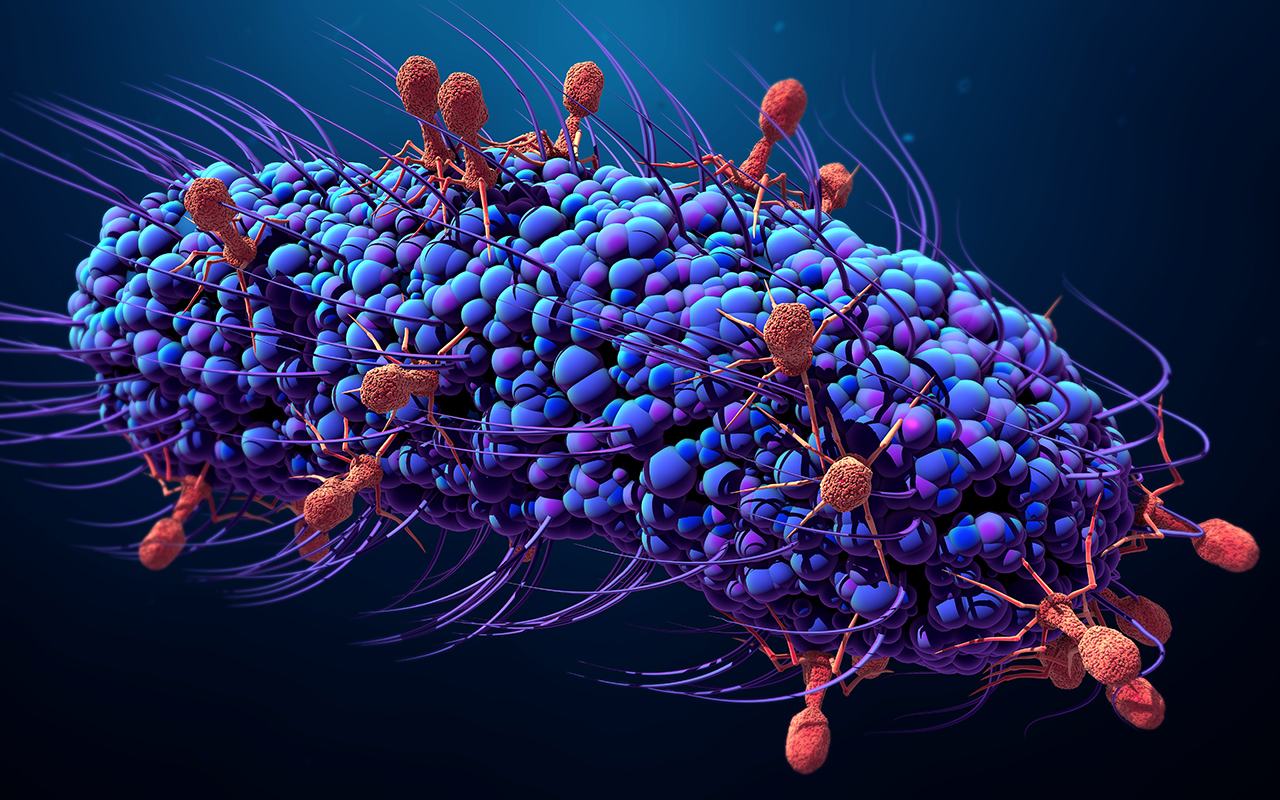

Genetically modified bacteriophage tested in a patient with cystic fibrosis

The first use of genetically engineered bacteriophages to treat a widespread, antibiotic-resistant mycobacterial infection in a human patient is reported in a case study published in Nature Medicine. Bacteriophage therapy is an alternative approach to managing antibiotic-resistant infections. It is designed to work by treating a patient with a virus that invades bacterial cells, causing these cells to die. Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and the Greater Ormond Street Hospital described a 15-year-old patient with cystic fibrosis and a chronic infection of Mycobacterium abscessus, a drug-resistant bacterium. The patient received a double lung transplant to treat the cystic fibrosis. The transplant was uncomplicated, but the mycobacterial infection persisted and became widespread, infecting the surgical wound site, liver, and more than 20 other locations on the patient’s skin, despite antimicrobial therapy. The researchers identified and genetically improved bacteriophages that could eliminate the specific mycobacterial strain that infected the patient. They administered a three-phage cocktail both intravenously and topically to the infected skin lesions, with no adverse effects. Over the course of 6 months of treatment, the patient experienced clinical improvement: the surgical wound and other infected areas of the skin healed, and only one new lesion appeared. As this was a case study, the authors were unable to conclude definitively whether the patient’s clinical improvement was due to the bacteriophage therapy. However, their findings encourage further investigation into the use of bacteriophages to treat antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

Rural lifestyles driving obesity

Researchers from the universities of Sydney, Queensland, Adelaide, Melbourne, Western Australia and New South Wales, as well as others from Flinders University, La Trobe University and Imperial College London, have found that the global rise in body mass index (BMI) seen over the past 30 years is largely due to increases in the BMI of rural populations. Published in Nature, the study analysed 2009 studies of over 112 million adults, which enabled the researchers to assess the changes in BMI that occurred in 200 countries from 1985 to 2017. They found that more than 55% of the global rise in BMI since the 1980s came from rural populations. In some low- and middle-income regions, this increased to more than 80%. The findings reflect the fact that, with the exception of women in sub-Saharan Africa, BMI is rising in rural areas at the same rate as or faster than in cities. The authors argued that poor, rural communities may be swapping an undernutrition disadvantage for a more general malnutrition disadvantage that entails excessive consumption of low quality calories. They called for an integrated approach to change the focus of international aid from just undernutrition, and broaden it to enhance access to healthier foods in both poor rural and urban communities.

Time for a reboot of ethics in China

The shocking news in 2018 that scientist He Jianku claimed to have helped to create genome-edited twins set off a period of soul-searching among China’s scientists and regulators. A group of Chinese researchers, writing in Nature, say that China is at a crossroads, and the government needs to make substantial changes, including closer monitoring of gene-editing centres and in vitro fertilisation clinics. The authors reflected on “what the incident says about the culture and regulation of research in China” and on “what long-term strategies need to be put in place to strengthen the nation’s governance of science and ethics”. The government needed to strengthen education and training in bioethics as well as in scientific and medical professionalism at all levels. “The ‘CRISPR babies’ scandal must catalyse an overhaul of science and ethics governance in China,” they concluded.

more_vert

more_vert

“Researchers from Royal Melbourne Hospital, the University of Melbourne and Monash Health, have found that the time to treat patients with ischaemic stroke can be doubled.”

No they didn’t. They found that there was no statistically significant difference for the primary outcome. What is the point of doing statistical analysis if you are going to ignore it and quote your raw data and dress it up as positive?

The EXTEND trial gives hope for improved recovery from stroke. However before concluding that the time window can now be put at 9 hours, it is worth noting what the study authors said in the publication itself: : “Because of the limited power of our conclusions as a result of premature termination of the trial and the lack of a significant between-group difference in the secondary outcome of functional improvement, further trials of thrombolysis in this time window are required”.

It is odd that the Stroke Foundation is more optimistic than the study itself. As with many interventions, and especially with stroke, it would be prudent to be a little more cautious before widespread implementation.