ADVANCED brain imaging is playing a critical role in the revolution in stroke medicine, according to an Australian stroke imaging expert, who says we may soon replace the “time clock” with the “tissue clock” in stroke management.

Professor Mark Parsons, research leader in acute stroke imaging, Professor of Neurology at the University of Melbourne, and Director of Neurology at Royal Melbourne Hospital, said advanced brain imaging played a crucial role in optimising the use of reperfusion therapies.

“All patients being assessed for reperfusion therapy should have perfusion imaging as routine to allow us to assess how much tissue is irreversibly injured (infarct core) and how much is salvageable (ischaemic penumbra),” he said.

“[Imaging] allows us to extend the treatment window for reperfusion therapy up to 24 hours. We should still try to treat as quickly as possible once we have the imaging. Essentially, we are now looking at replacing the ‘time clock’ with the ‘tissue clock’ using perfusion imaging.”

Professor Parsons’ comments came as the MJA published a narrative review on advances in stroke medicine.

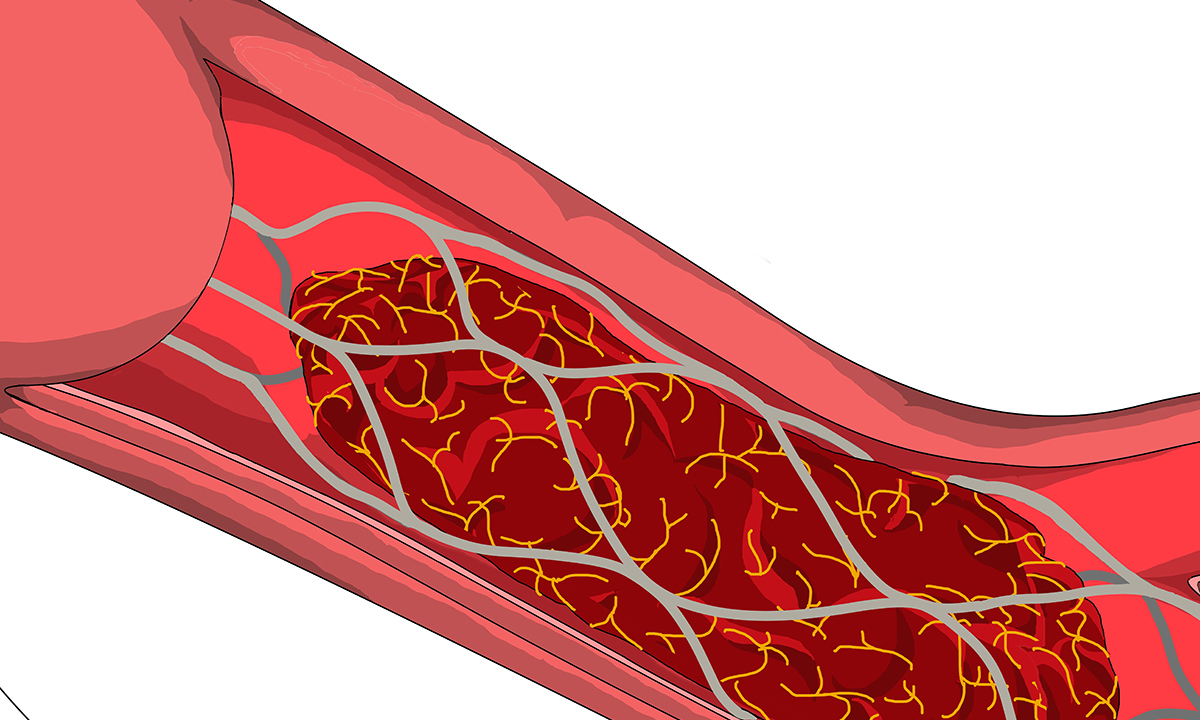

Professor Bruce Campbell, consultant neurologist and Head of Stroke at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and chair of the Stroke Foundation’s Clinical Council, wrote in the MJA that reperfusion therapies, such as intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular thrombectomy, for ischaemic stroke had “dramatically reduced disability and revolutionised stroke management”.

“Thrombolysis with alteplase is effective when administered to patients with potentially disabling stroke, who are not at high risk of bleeding, within 4.5 hours of the time the patient was last known to be well,” he wrote. “Emerging evidence suggests that other thrombolytics such as tenecteplase may be even more effective. Treatment may be possible beyond 4.5 hours in patients selected using brain imaging.”

Professor Campbell noted that while 20% of patients with ischaemic stroke are eligible for thrombolysis in the 4.5-hour time window, only about 13% of patients are receiving this treatment.

“There is still room to improve the proportion of patients getting thrombolysis,” Professor Campbell said in an InSight+ podcast.

He added that about 10% of all patients with ischaemic stroke would be eligible for endovascular thrombectomy.

“That might sound like not too many patients, [but] it is the group of patients who have the highest risk of disability and death, so it makes a big impact on the disability burden,” he said.

Professor Campbell said thrombectomy was indicated for patients with a large blocked vessel, such as the carotid or proximal middle cerebral artery. In 2018, the time window for thrombectomy was extended to 24 hours, enabling treatment of some patients with wake-up stroke.

Professor Geoffrey Donnan, Professor of Neurology at the University of Melbourne, said brain imaging had revolutionised stroke management.

“Firstly, by dichotomising patients into haemorrhagic versus ischaemic stroke and, secondly, by identifying viable penumbral tissue. This means we can increasingly extend the time window for therapy if patients are carefully selected,” he said. “This does not diminish the need to treat every stroke as a medical emergency since we are losing about 2 million neurons per minute after stroke onset. Earlier treatment dramatically improves outcomes.”

With Professor Stephen Davis, Professor of Translational Neuroscience at the University of Melbourne, Professor Donnan is co-leading the Extending the Time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits (EXTEND) trial.

“We have shown that intravenous thrombolysis with [tissue plasminogen activator] improves outcomes when given up to 9 hours post stroke, or [for patients] awakening with stroke, when selected with modern brain imaging techniques. This involves brain perfusion assessment to obtain an estimate of the presence of viable (penumbral) brain tissue,” Professor Donnan said. “The evidence, together with a meta-analysis we have completed, including EXTEND with other smaller less conclusive trials, should influence guidelines to change the time window from its current 4.5-hour limit for intravenous thrombolysis.”

In the InSight+ podcast, Professor Campbell said there were many barriers to accessing reperfusion therapy in Australia, including fluctuating community awareness of the FAST (“facial droop, arm weakness, speech disturbance, time to call 000”) message.

“First, the patient, or the person around them, needs to recognise it’s a stroke – without that you don’t get the 000 call,” Professor Campbell said. “Every time there is a TV campaign with the FAST message, awareness goes up for a few months and then it starts to drift down again, so we need to be constantly battering the community recognition of stroke.”

Professor Donnan said a further barrier to reperfusion therapies was inequitable access to stroke units, which was particularly problematic in rural and regional Australia.

“We need better access for all Australians to modern stroke care, a national approach to standardised quality care to reduce inequalities, and outcomes monitoring with an expansion of the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry (AuSCR),” he said. The AuSCR is currently in around 80 hospitals Australia-wide.

Professor Donnan who, with Professor Davis, jointly led the establishment of Australia’s first and only mobile stroke unit, which launched in Victoria in 2017, said his team was also seeking to get a stroke air ambulance off the ground.

He said he hoped that that the next 5–10 years would see the rollout of telemedicine Australia-wide, as it was currently available in Victoria, but was “patchy” elsewhere.

Professor Donnan said new interventions, including improved thrombolytics and clot retrieval devices, and better stroke recovery interventions were also on the horizon.

Professor Parsons said a key challenge was a shortage in clinical expertise. “We still don’t have enough expert stroke physicians and stroke nurse experts around Australia,” he said.

Imaging too would have an expanded role, he said. “Multimodal computed tomography (CT) including perfusion CT should be routinely performed in all [patients with acute stroke], including those in regional and rural Australia,” Professor Parsons said.

Professor Campbell said there were still many frontiers in stroke medicine.

“We still need to get the systems right, and we need to continue to expand our understanding of who can benefit [from reperfusion] because these … therapies are very powerful and we probably still haven’t expanded to the limits of what we can achieve.”

more_vert

more_vert

As an elderly retired physician taking riveroxaban as an anticoagulant for which there is no currently available reversing agent, how is a stroke managed with thrombolytics in such patients>?