OVER the coming few days, peak eye health bodies across the globe will be joining forces in a concerted effort to raise awareness of a common, underdiagnosed eye disease as part of World Glaucoma Week, which kicked off on Sunday, 11 March.

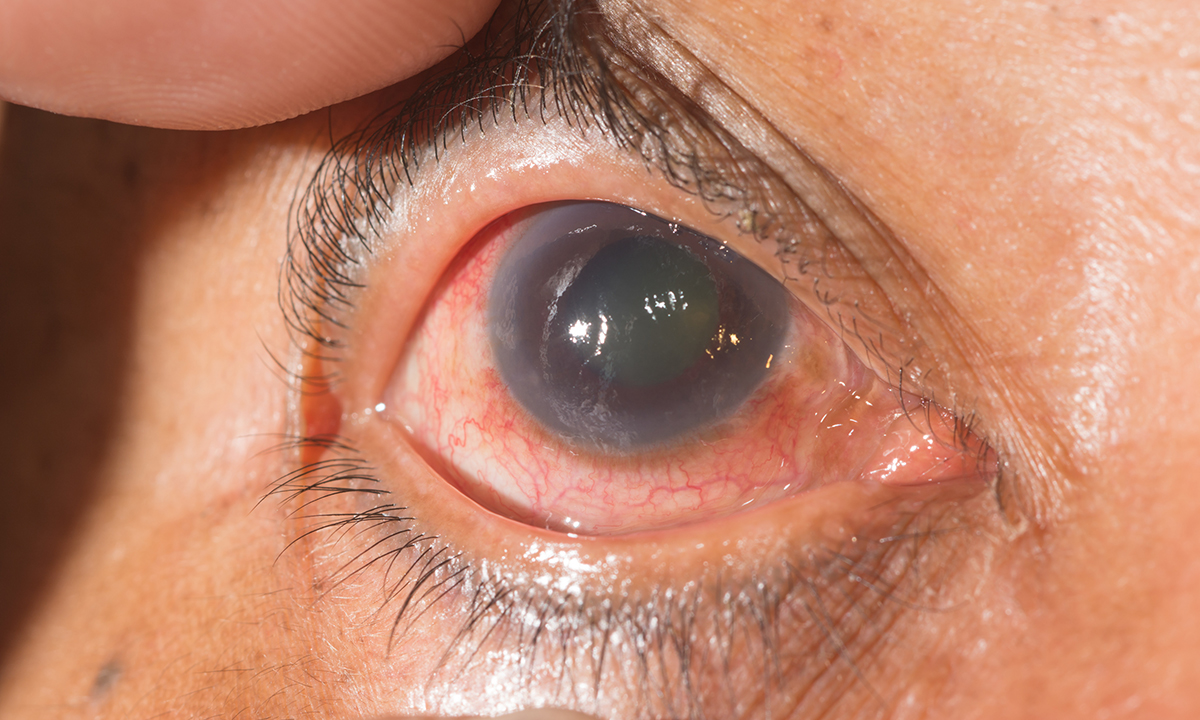

Glaucoma is not one single disease but a collection of conditions in which increased pressure in the eye is associated with damage to the optic nerve, eventually leading to blindness. By far the most common type is open-angle glaucoma, which accounts for around 90% of all cases. Increasing age is a predictor, as is having a family member with the disease.

“The biggest problem we have with glaucoma is there are no early symptoms,” says optometrist Dr Ben Ashby, who is Head of Optometry at Specsavers and a spokesperson for Glaucoma Australia. “There’s nothing we can go to the community with and say, ‘If this happens, go and get your eyes checked’. Unfortunately, we have to wait for people to turn up at their optometrist, usually for something else, and then as part of the examination we pick up their glaucoma.”

Glaucoma starts as a very gradual loss of peripheral vision – far too slow to notice – that is completely irreversible. But although nothing can be done to restore this lost vision, the good news is that as soon as glaucoma is diagnosed, further loss can usually be stopped with a simple eye drop treatment.

“So the key problem is underdiagnosis,” says Dr Ashby. “We estimate there are around 300 000 people in Australia with glaucoma, but around half of those cases are undiagnosed. That’s 150 000 people who are irreversibly losing their sight.”

Dr Ashby says that GPs have a key role in getting these people diagnosed and treated.

“There’s a good chance these people are not getting their eyes checked, but they probably are seeing a GP. The low hanging fruit for GPs is familial risk. If someone has a first-degree relative with glaucoma, then there’s a 23% chance they’ll get it themselves. If they have a relative with advanced disease, then the risk increases to almost 50%. So if GPs ask their patients aged over 40 years if they have a relative with glaucoma and get them referred if they do, they could catch a lot of this undiagnosed population.”

Sydney-based ophthalmologist Professor Ivan Goldberg, who is the current chair of the World Glaucoma Week Committee, agrees that GPs have a critical role in getting people diagnosed. But he says that there are also other areas where GPs can help in managing the disease.

“Treatment adherence and perseverance are major problems. They are as challenging to the patient as they are in any chronic asymptomatic disease where treatment side effects are more of a problem to the patient than the disease itself. If eye drops sting, that’s what they focus on, not on the fact that the treatment is lowering pressure and maintaining their sight. It’s an area where GPs can help by talking to the patient about any issues with their drops, and if there are any problems, alerting the ophthalmologist so alternative strategies can be trialled.”

Professor Goldberg says that another issue GPs need to be careful about is drug interactions.

“A lot of GPs have patients being treated with eye drops. They need to remember that eye drops mimic intravenous medications. Most people don’t think of them as relevant in taking a medical history, but because of direct absorption from the surface of the eye into the bloodstream, these drops can have effects on general health and significant interactions can occur. For example, if you’re using a topical b-blocker, that can interact with a systemic b-blocker and/or calcium channel blocker, and enhance the side effects.”

Glaucoma is currently an area of intense research focus, with Australia punching well above its weight, says Alex Hewitt, an Associate Professor in Ophthalmology at Hobart’s Menzies Institute for Medical Research. Dr Hewitt has been closely involved in work on identifying genes involved in developing glaucoma – research that he says will have a powerful downstream clinical effect.

“The work started in Tasmania in the 1990s with the Glaucoma Inheritance Study and continued in Adelaide, where Professor Jamie Craig has helped build up the world’s largest cohort of people with advanced glaucoma. That’s led to the discovery of many common genetic variants for the disease. And now we’re not too far off having a very robust polygenetic risk score for glaucoma that we could implement in clinical practice. That’s terribly exciting, because of all the ophthalmic diseases, glaucoma is one where if you intervene early, you can stop blindness occurring.”

He says that while today, all people aged over 40 years are advised to get their eyes checked every 2–3 years, a polygenetic risk score could help identify those who need closer monitoring.

“We’d be categorising people into very low risk who might only need a check every 5 years, or at the opposite end of the spectrum, there will be those at very high risk, who will need to be seen every 9–12 months. That will save a lot of money because on the one hand, you’ll be preventing blindness, and on the other, you’ll rationalise the screening.”

Professor Goldberg agrees that it’s an exciting time to be involved in glaucoma, with advances in many aspects of its management and treatment.

“The diagnosis is getting easier because devices are becoming available which will allow people to take their eye pressure themselves at home, just like blood pressure. They’ll also be able to get photos taken of the optic disk with a smartphone that will allow diagnosis via telemedicine. New drugs are likely to be available in the next 2–3 years, and new surgical procedures as well are being trialled around the world, including in Australia. Things are moving very quickly.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert

Knowing that the risk of glaucoma is 10 times greater for those with an affected first degree relative, and that: “First degree relatives of people with glaucoma have an almost 1 in 4 chance of developing glaucoma in their own lifetime” https://www.healthfitnesz.com/glaucoma-symptoms-remedies/

150,000 Australians who have undiagnosed glaucoma equates to 4 patients for each of the 35,000 GPs in Australia. You can imagine that it is pretty hard to for GPs to try to ‘remember’ to keep looking for those four people amongst their patients.

Knowing that the risk of glaucoma is 10 times greater for those with an affected first degree relative, and that: “First degree relatives of people with glaucoma have an almost 1 in 4 chance of developing glaucoma in their own lifetime” https://www.glaucoma.org.au/about-glaucoma/facts-and-faqs/ reinforces the importance of our clinical systems being able to record family history in a structured way, so that a diagnosis of glaucoma in a relative can be recognised by the computer system, which can then automatically generate and alerts and reminders the patient and to the GP to have assessments for this at appropriate intervals. My fifth article in my current series in Medical Observer about how to improve the clinical software that GPs use, published nearly two years ago https://www.medicalobserver.com.au/professional-news/lack-of-focus-on-family-history-is-a-missed-opportunity-for-gps, addressed this issue. To my knowledge, apart from Visual Outcomes, which is seeking to establish itself in the GP market, and which apparently already does have this functionality, none of the vendors of clinical software commonly used in general practice has taken up my proposal. .

I note that https://www.glaucoma.org.au/about-glaucoma/facts-and-faqs/ says: “Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide”, while https://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/diabetes-in-australia says: “Diabetes is the leading cause of preventable blindness in Australia.” These statements might not be incompatible, but I would be interested to know whether and how they can be reconciled.

the most import thing all medical practitioners, including GPs can do it to tell any of their patients that they know have glaucoma the they, the patient, must alert their first degree relatives that they are at risk too. a family history can increase the risk of glaucoma in first degree relative 8 times! so altering brothers and sisters, daughters and sons to tell their eye care provider at the next exam that they have a relative with glaucoma is really important.

half of those with glaucoma are undiagnosed, and half of these have had an eye exam in the last 12 months and their glaucoma has been missed. if they knew and alerted the eye care provider of their family history a much more careful examination would have been done. the problem is most people, about 75%, do not know of their family history.

pharmacists should also play a key role giving the same message to everyone who has glaucoma drops on prescription.

“So if GPs ask their patients aged over 40 years if they have a relative with glaucoma and get them referred if they do, they could catch a lot of this undiagnosed population.”

The issue is: how can GPs remember, amongst their many many other tasks, to do this reliably, consistently and thoroughly? The answer is: they can’t. No human can.

In many or most of the clinical software ware packages marketed for use in Australian general practice, family history can be recorded only as free text. This prevents the computer system from being able to remind GPs and the patient to ask about family history of glaucoma. Even if family history was able to be recorded in a structured way to enable such automated reminders, the next hurdle is that the software needs to be able to recognise that the patient has had a glaucoma assessment performed. Currently none do this. If software used by optometrists and ophthalmologists such as the Oculo system http://www.connect.oculo.com.au/ could communicate that information in a structured way to general practices’ software systems, this could be achieved.

I addressed this issue of how GPs can ‘remember’ to consider whether the patient needs assessment for a huge range of possible conditions, in my article in MJA Insight https://www.doctorportal.com.au/mjainsight/2016/31/give-gps-practical-help-not-another-lecture/ .