ON the eve of World Sepsis Day, Australian researchers are “on the verge” of breakthroughs in the management of sepsis, say experts.

“We need to be able to show the impact of these interventions, but we can’t do that unless we are able to record the patients who truly have sepsis,” says Professor David Paterson.

Professor Paterson, Director at the University of Queensland’s Centre for Clinical Research, said that research published in the MJA was an important step in improving the “counting” of cases of sepsis and septic shock in Australian hospitals.

“If we are going to be able to do all these great things to alter the course of sepsis — and we know that a person presenting to a hospital with sepsis has a higher chance of dying than a person presenting with a heart attack — first of all, we have to count it properly,” said Professor Paterson, who is also a consultant infectious diseases physician.

Writing in the MJA, researchers have reported the findings of a prospective cohort study comparing estimates of the incidence and mortality of sepsis using clinical diagnosis or the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Centre for Outcome and Resource Evaluation (ANZICS CORE) database methodology.

The researchers found that when compared with clinical diagnosis, the ANZICS CORE database criteria significantly underestimated the incidence of sepsis and overestimated the incidence of septic shock. The database methodology also resulted in lower estimates of hospital mortality for each condition.

Of the 864 patients admitted to the 60-bed intensive care unit (ICU) in the 3-month study period, 146 were diagnosed with sepsis using clinical criteria, and 98 were diagnosed using the database definition.

The researchers reported that 70 patients had a false negative diagnosis of sepsis and 22 patients were given a false positive diagnosis using the database method.

The most frequent reason for the false negative diagnosis was the absence of an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III diagnostic code for sepsis or infection (81%), and that sepsis was diagnosed more than 24 hours after admission (36%) — the ANZICS CORE dataset captures only cases of sepsis recorded in the 24 hours after admission to an ICU.

In half of the false positive cases, the organ dysfunction found was not due to infection, and in a further 36% of cases, the patients did not meet the clinical criteria for organ dysfunction.

Associate Professor Craig French, Director of Intensive Care at Western Health, Melbourne, said that it was not surprising to see the variation reported in the study given the different definitions applied. However, he noted, the clinical diagnostic model used in the study would not be practical outside a research environment.

“The clinical criteria used in this study involved daily assessment and data collection, and if there was uncertainty, direct questioning of the treating ICU specialist as to whether infection was present or not,” Professor French said. “This is not feasible outside a research environment. It is possible that as electronic health records evolve such information could be contemporaneously documented for later retrieval.”

In an exclusive MJA InSight podcast, co-author of the study Professor Simon Finfer acknowledged the impracticality of routine use of clinical diagnosis.

“My proposal would be that we continue to use administrative datasets for disease surveillance, which is the only practical approach, but that we periodically calibrate these datasets using clinical diagnosis,” said Professor Finfer, a senior staff specialist in critical care at Royal North Shore Hospital and director of the ICU at Sydney Adventist Hospital.

He said that a key challenge in accurately identifying the incidence of sepsis was the lack of a diagnostic test for the condition.

“Apart from those of us who are intimately involved in treating people with sepsis and researching sepsis, it’s been a bit of a Cinderella condition that is poorly understood,” he said.

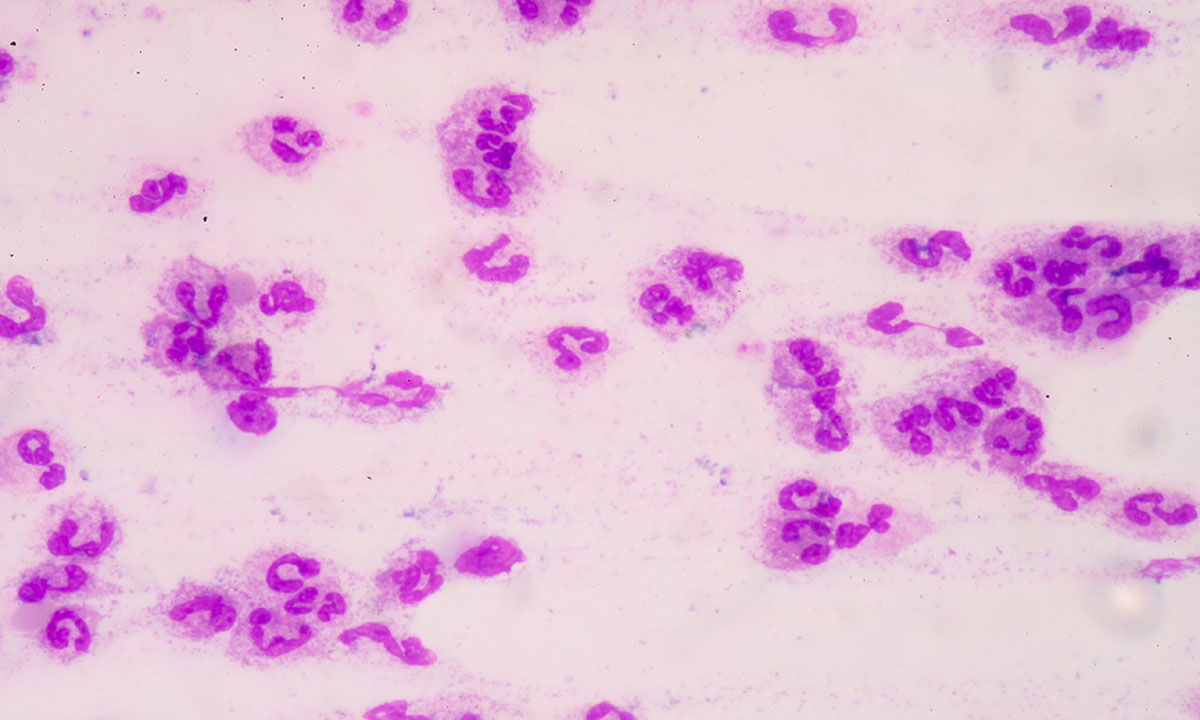

“There’s no blood test to confirm sepsis, there is no histological test to confirm sepsis, there’s no radiological test to confirm sepsis, so the gold standard for the diagnosis is still a clinical one.”

Professor Paterson said that several Australian research groups were working to develop a diagnostic blood test for sepsis, but such a tool was still some years away.

“[A diagnostic test is] the holy grail, but I think it’s something that is achievable, certainly in the next decade, and Australia is well placed to be world leaders in that,” Professor Paterson said.

Professor Finfer, who is also a professorial fellow at the George Institute for Global Health, said that work was also needed to improve the awareness of sepsis in both the general and medical communities.

“We have a major awareness problem,” Professor Finfer said.

“Outside of the ICU, the most important thing is that people actually start to accurately and appropriately use the term sepsis and document it in the medical record.”

He pointed to a survey that he had conducted that found that only 40% of Australians had heard of sepsis, and only 17% were aware that fever and shivering could be signs of sepsis. And just 1–2% of Australians surveyed were aware that rapid heart rate, rapid respiratory rate, low urine output, mental confusion, and skin rashes could be indicative of sepsis.

Professor Paterson agreed that awareness of the signs of sepsis was low.

“We have done such a great job with heart attacks. Most people know that if they have chest pain, it could be a heart attack and they need to get to hospital,” Professor Paterson said. “We need to get the same message out there for sepsis.

“It’s a more difficult, more diffuse message – sepsis is blood pressure, temperatures, organ system failure, it’s not so simple or evident to clinical staff sometimes – and that’s what makes it tough.”

World Sepsis Day is 13 September.

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert