WE are excited to announce the establishment of the first National Health and Medical Research Council Centre (NHMRC) for Research Excellence in Food Retail Environments for Health.

With unhealthy diet representing the leading risk factor for chronic disease worldwide, and in high income countries such as Australia being a cause of many poor health outcomes, including overweight and obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, dental decay, and mental health problems, there is a global imperative to act to improve population diet.

In Australia, the majority of the population does not meet national dietary guidelines. We consume too much unhealthy food and drink, such as sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs), and too little healthy food, like fruit and vegetables. An unhealthy diet is Australia’s key modifiable risk factor, resulting in diet related factors making up five of the top 10 risk factors driving death and disability in Australia. It is associated with greater social disadvantage, and is an important contributor to Australia’s inequalities in health. With over one-third of energy intake coming from food which is high in saturated fats, sugars, salt and/or alcohol, there is substantial opportunity for effective interventions to improve population health, equity and wellbeing. Action is needed now if Australia is to turn the tide on our growing burden of diet-related disease. How is it possible that, despite global agreement on the now critical need to improve population diet, little progress has been made?

At the core of the problem lies the fact that Australian food retail environments (from supermarkets, through remote stores to the food service sector), where we source most of the food we consume, currently incentivise and promote unhealthy food choices, leading directly to poor health outcomes. Existing calls for change have focused largely on encouraging individuals to improve their food choices, which – while important – has proven to be an inadequate approach to improving population diets. Global recommendations have typically paid little attention to the role of the retailer in creating environments that encourage healthy food purchases. We must explore new solutions that are more robustly positioned within the reality of our large and complex food system, so as to be feasible for retailers while also improving population diets. These solutions must act across all our food retail environments to improve inequalities in diet. Research is urgently needed that demonstrates how healthy food retail can become the new norm for food business by promoting diets that meet national dietary guidelines and are rich in healthy core foods like fruit and vegetables, while reducing excess purchase of discretionary food and drink (those high in saturated fat, added sugars, salt and/or alcohol).

Over the past decade, we, and others, have developed compelling evidence of the untapped potential and power of food retailers, suggesting that they represent a significant opportunity to more rapidly shift our food environments to healthier food and drink provision. With nearly all food being purchased in some type of retail setting (around two-thirds from supermarkets alone), and the retail environment having a powerful effect on purchasing decisions, it is clear that food retailers are critical gatekeepers of the environment in which we find and buy our food (here).

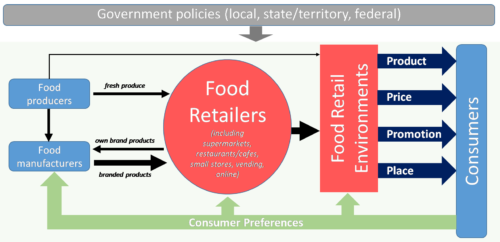

We must now work with these gatekeepers to transform the food retail environment to turn the tide of our declining population health – and we must do so by aligning with food retailers’ primary goals: creating value for their customers, and profit for themselves and their shareholders. Greater purchasing and profitability are commonly encouraged by retailers through the classic “four Ps of marketing” (price, promotion, place, and product), which interact with consumers’ personal circumstances and preferences to influence their purchasing decisions and broader social norms. Further, retailers’ negotiations with manufacturers shape supply and thereby impact what is available for us to buy.

Legend: Factors affecting the healthiness of the food retail environment

Lastly, retailers often have a connection to their community, are beholden to local policy and value community standing, which in turn can increase the relevance of health and wellbeing outcomes to the retail business model (here, here, here, here and here). Food retailers play a pivotal role in influencing food purchases. But why have so few retail environments changed for the better? One answer lies in retailers’ assumption that healthy food retail will reduce profitability and customer satisfaction, with no incentive offered to retailers to change. However, recent evidence is challenging this assumption, demonstrating that interventions that promote healthier food retail can be feasible and profitable, and align with growing customer demand (here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here).

We have examples of partnership work with many of the early adopters of healthy food retail across Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK. These retailers have included supermarket chains, stores in remote and underserved communities, and food service outlets in hospitals, schools, sports and recreation centres, and universities. Different interventions were trialled, including strategies focused on multiple elements of the food system and including the “four Ps of marketing”, both singly and in combination.

Evaluations of these interventions have led to ongoing research as well as lasting policy and practice changes such as: reduced sugary drink sales across YMCA Victoria (a statewide leisure service provider); less than 20% of food and drinks available across Western Leisure Services in Victoria classified as unhealthy (according to state government guidelines); policies that preference healthier food and drinks such as reduced price of bottled water and no freight charged on fruit and vegetables, in stores owned by the Arnhem Land Progress Aboriginal Corporation, Outback Stores and Mai Wiru Regional Stores Council; and implementing a better choice healthy food and drink supply strategy for Queensland health facilities in over three-quarters of health facilities throughout Queensland.

We are also seeing the power of robust health evidence in encouraging retailers to experiment with healthier retailing and scale-up what works. Following positive evaluation findings, the YMCA sugary drink removal intervention was implemented by Western District Health Service (35 facilities), across the Victorian Great South Coast region, and by New South Wales Health across all NSW Health facilities. Similarly, trials of three healthy supermarket interventions in three stores (with four control stores) from a single independent chain have led to a scaled up multicomponent intervention being rolled out across a further 11 stores in regional Victoria.

These successful initiatives highlight the promise of this research field. However, they were not set up to yield comparable analytic data, but developed locally and independently in response to social, regulatory and market pressures and opportunities.

We need to know more about how diverse businesses could learn from successful outcomes, the conditions that enabled them, and more about outcomes of other related interventions in different contexts. What investments, risks, and benefits are involved for food retailers when implementing such change and what is the potential for at-scale, sustainable implementation of healthy food retail interventions to equitably improve population health? Only a deeper understanding of the answers to these questions will allow us to translate individual intervention success into broader, system-level recommendations, and provide the methods and tools required to support them.

The time is right for a Centre for Research Excellence in Food Retail Environments for Health to build and substantiate this business case, as a critical lever we must pull to move society toward healthy food retail environments that promote healthier diets for all our citizens, now and into the future.

Anna Peeters is Director of the Institute for Healthcare Transformation, and Professor of Epidemiology and Equity in Public Health, at Deakin University. She is Past President of the Australian and New Zealand Obesity Society and in 2014 was awarded the World Obesity Federation Andre Mayer Award and a Churchill Award.

Julie Brimblecombe is Associate Professor of Public Health Nutrition at the Department of Nutrition, Dietetics and Food, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, and has an honorary appointment with Menzies School of Health Research. She is a dietitian with extensive experience in public health nutrition in the remote Indigenous Australian and Pacific Island contexts.

Steven Allender is Professor of Public Health and founding Director of the Global Obesity Centre at Deakin University, a World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Obesity Prevention. Steve leads an NHMRC Partnership grant targeting childhood obesity and co-leads an NHMRC Australian Centre for Research Excellence in Obesity Policy Research and Food Systems.

Dr Adrian Cameron is a senior research fellow at the Deakin University Global Obesity Centre (GLOBE). He leads a NHMRC/VicHealth funded partnership to test healthy eating interventions in the supermarket setting.

Professor Amanda Lee is Senior Advisor at the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre and also based at the University of Queensland. She has more than 35 years’ experience in academic, government and community-controlled sectors, in chronic disease prevention, Indigenous health, and food, nutrition and public health policy.

Gary Sacks is an Associate Professor in the Global Obesity Centre at Deakin University, where his research focuses on policies for the prevention of obesity.

Professor Marj Moodie is the Head of Deakin Health Economics at Deakin University. Her own research as a health economist is focussed on economic evaluation and priority setting, primarily in the field of obesity, non-communicable diseases and stroke.

Professor Cliona Ni Mhurchu leads a Population Nutrition Research Programme at the National Institute for Health Innovation. Her research program evaluates population dietary interventions and policies, such as food taxes and subsidies, front-of-pack nutrition labels, scalable healthier food choice interventions, and product reformulation.

Boyd Swinburn is the Professor of Population Nutrition and Global Health at the University of Auckland and Alfred Deakin Professor and Director of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Obesity Prevention at Deakin University in Melbourne.

Bruce Neal is Professor of Medicine at UNSW Sydney, where he leads food policy research at the George Institute for Global Health.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or MJA InSight unless that is so stated.

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert

The other important thing that needs to be addressed at the same time is how ‘healthy’ is defined. For example by sugary drinks, do they only include those with added sugar, leaving fruit juice with all the ‘natural sugar’ of 6 oranges per glass in the healthy areas. There is so much misinformation on nutrition, perpetuated by the food industry that I see many people making poor choices without even knowing it.

Brian Wansink’s work on this area of how exposure, rather than intent, drives purchasing (from Cornell University) is interesting reading (although there are criticisms of scientific method). The shops all know that if they put the milk at the very back, forcing you to walk past the biscuits and muffins, with the lollies and trashy magazines right where you wait for the check out, you buy more than just milk.

Legislation works in diminishing access to cigarettes and hard core pornography, by literally putting them out of sight, under the counter, and not for sale to minors.

It would be similarly unpopular but effective to legislate that healthy products had to be at the front of the shop, unhealthy at the back, and banning the sales of any product which did not have the relevant government healthy rating to children under 18. Those consenting adults who wish to buy a 24-pack of Coke can make the trek to the back of the store, and ask the shop assistant for their plain labelled pack, embellished with a life-sized gangrenous foot picture, in the hushed tones of a 1950s condom buyer.

All shoppers could be tempted by the artful eye-level displays of broccoli and grapefruit, right at the checkout.

For the online shopper, when you type in ’24 pack of glazed doughnuts’ it would ask, “did you really mean Brussels Sprouts?”, then when you try to click through, a gangrenous foot video plays compulsorily, with a stern voiceover by Cate Blanchett or Sam Neill, “This is the diabetic foot of a doughnut eater…”.

Professional sellers know what sells, which is why the chocolate, not the carrot, is on display at the checkout. Soft persuasion did not work with tobacco or alcohol. It is a failure to pro-actively legislate which allows a 16yr old to buy a can of sugary drink, but not a 3cm blade Swiss Army knife, despite the higher lethality of the sugar.

Should this be taken one level higher where such urgent needs are legislated?