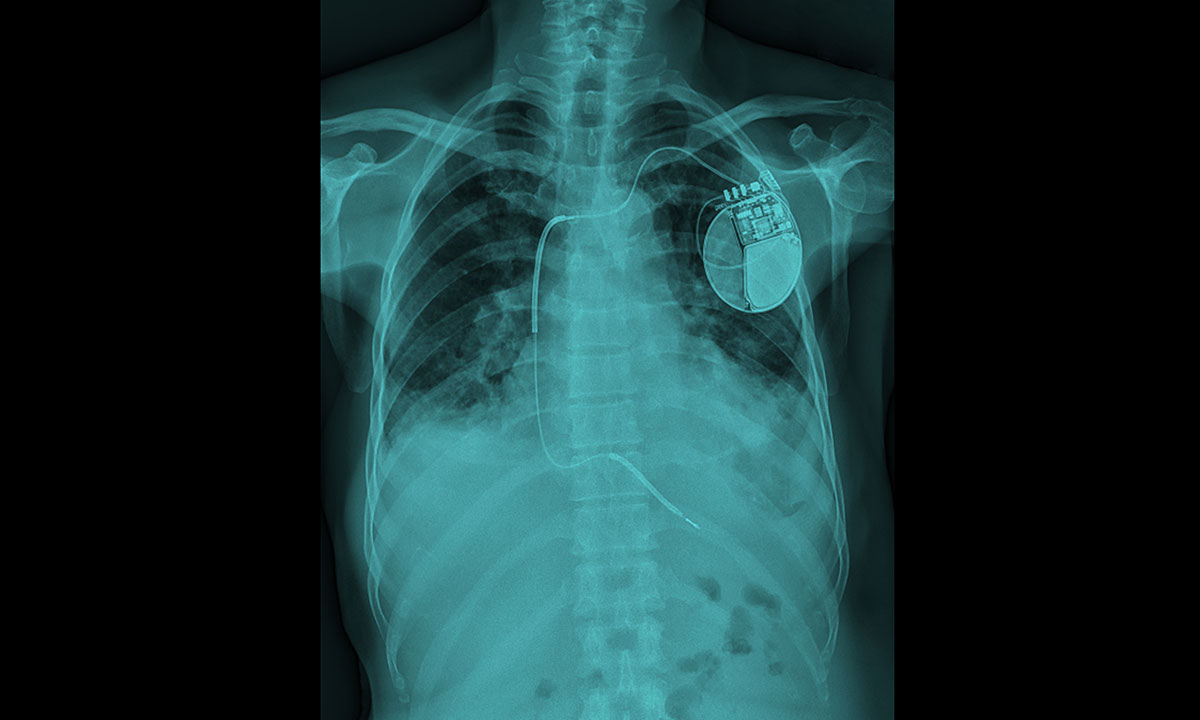

IMPLANTABLE cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) procedures are on the rise in Australia, particularly in the over-70s age group, but may be of questionable value in the oldest patients, say experts.

A retrospective analysis of procedures data in the Australian National Hospital Morbidity Database, found that the number of ICD procedures in Australia had increased more than three-fold in the 13 years to 2015, increasing from 1844 in 2002–03 to 6504 procedures in 2014–15. More than 75% of procedures were in men.

The study, published in the MJA, reported that in 2014–15, the ICD insertion rate was 78.1 per 100 000 population in people aged 70 years or older, 22 per 100 000 in those aged 35–69 years, and 1.4 per 100 000 in people aged under 35 years.

Glenn Young, a cardiologist with Adelaide Cardiology and associate professor at the University of Adelaide, said that it was crucial to focus on patient-centred care, particularly when discussing ICD therapy in older Australians.

“You have to look past simply the technology and the science,” Professor Young said. “It’s [essential] that you individualise the prescribing of this therapy to each patient, and where that’s really important is in the older patient.”

Professor Young said that an elderly patient may tick all the medical boxes for having an ICD, but the device may provide minimal benefit.

“You might be faced with a patient who is 85 years old, who has all of the medical indications [for an ICD], but then you talk to the patient and they say ‘well, I lost my partner a couple of years ago, all my kids live away, life is okay’,” he said. Some of these patients want therapy that will maintain or improve quality of life, he said, but not necessarily prolong it.

Professor Young said that the annual risk of having a fatal arrhythmia in this older cohort eligible for an ICD was still only about 4–5%.

“The really important thing is that you have the discussion with the older patient, and give them some real clarity around what they would gain by putting a device in. For most people, an ICD doesn’t change their quality of life.”

Dr Sarah Zaman, an interventional and consultant cardiologist with MonashHeart and Monash University, said that the increase in ICD procedures in patients aged over 70 years was not unexpected given our ageing population and the higher prevalence of coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction in this group.

“However, there was more recent evidence, particularly in non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy, of a lack of benefit of an ICD for primary prevention in patients over [the age of 75 years], presumably due to the competing risk of death from non-sudden causes,” she said. “It is imperative for trials to recruit more elderly patients, or to focus just on elderly patients to determine a benefit.”

Dr Zaman said that it was “very likely” that the oldest patients did not benefit from ICD implantation as much as younger patients due to other competing risks of death.

Dr Zaman said that the overall increase in ICD procedures reflected the evolving evidence since 2002 that demonstrated a survival benefit of an ICD in patients at risk of sudden cardiac death.

“What we see is an appropriate increase in ICD procedures with time,” she said. “In 2002, ICDs would have been used mainly for secondary prevention indications. However, over the past decade, many randomised studies have targeted primary prevention. These studies showed, particularly in patients with a previous heart attack, that ICDs prevented deaths. Based on many studies and experience in the public hospital setting, ICDs are actually underutilised for primary prevention, and waiting lists to receive an ICD are very long.”

Professor Young said that Australia’s increasing rate of ICD procedures partly reflected the ageing population, but the growth seemed to be “over and above” demographic changes.

Improved access to appropriately trained specialists was one factor driving the increase, he said.

“Electrophysiology is still a relatively young subspecialty,” Associate Professor Young said. “When I started putting these devices in more than 25 years ago, there were only a few people in South Australia who were capable of implanting these devices, and now there would be probably 15 or more.”

Professor Young said that greater awareness of the patients for whom these devices could be life-saving was a further reason for the growing number of procedures.

“Indication creep” – where the boundaries of clinical guidelines became blurred over time – may also be responsible for some of the increase, he said.

The MJA authors found that the reported complication rate associated with these procedures had fallen from 45% in 2002–03 to 19% in 2014–15. This decline partly reflected a change in the way complications were coded in the database.

They also found that the aggregated cost of hospitalisations for ICD procedures in the 5 years to 2014 was more than $445 million.

They said that when making decisions about recommending ICD therapy, a clinician must weigh its life-saving benefits against the potential harms, including ongoing device interrogations and battery replacement. They added that there were potential psychosocial burdens associated with ICDs, including device-related anxiety and post-traumatic stress after a shock.

Associate Professor Young said that potential psychological harms were an important consideration in deciding on device therapy. While technological advancements and improved expertise in device programming had reduced the number of unnecessary shocks patients received, he said some patients continued to struggle psychologically with the implanted device.

“A number of things can cause the devices to deliver a shock when the patient is not unwell, and if that happens repetitively, patients can often become psychologically stressed,” he said. “I have a not insignificant number of patients who need psychological and psychiatric help after going through that sort of experience.”

Professor Young said that more research was now needed into the older patients being offered ICD procedures, particularly to determine the cost effectiveness of the intervention in this cohort.

He said federal funding decisions were based on cost-effectiveness data in patients aged in their 60s.

“No one has done a large prospective study of cost effectiveness in the older age group, so we don’t really have that data about whether that’s money well spent or not.”

Dr Zaman said further investigation was also required into the low rates of ICD implantation in women.

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert

The implanting of ICDs in the older population is still required when the standard guidelines are met. The psychosocial and economic “burdens ” are interesting but none of these have concerned my patients who are very happy to know that they are unlikely to die of VF.

Not all have had a discharge but this does not mean that they did not fulfill standard criteria.

At present we do not have a long term effective agent for treating recurrent VT and amiodarone certainly has a poor adverse reaction profile.

A medicolegal point should be mentioned. Should a patient aged 75-85 + suffer a fatal cardiac arrest and standard criteria for an ICD were known by his cardiologist, the patient’s relatives may well be able to make a case of negligence against the cardiologist if an ICD had not been “prescribed”.